Component: 2011 Avalanche Chubie Rear Shock with independent hi/lo compression damping adjuster

Intended Use: Any and everything on the dirt

Size Tested: 8.5” (eye-to-eye length) x 2.5” (stroke) [216 x 63mm]

Shock weight (w/ 450lb spring): 930g. Shock body: 510g

Bike: 2010 Santa Cruz Nomad Mk II Aluminum Frame

Bike/Shock Weight: 32 lbs.

Rider: 5’8”, 165lbs. I prefer to jump over or around obstacles instead of plowing through them.

Test Locations: New Hampshire, Vermont, Utah, Colorado, British Columbia

Days Ridden: ~220 Days

Avalanche suspension sells shocks that are custom valved for the rider. Their products are designed to provide optimal suspension performance for individual users, instead of the average user. Their products break into two categories: (1) complete forks and rear shocks, and (2) replacement cartridges and shock rebuilds for common forks and shocks.

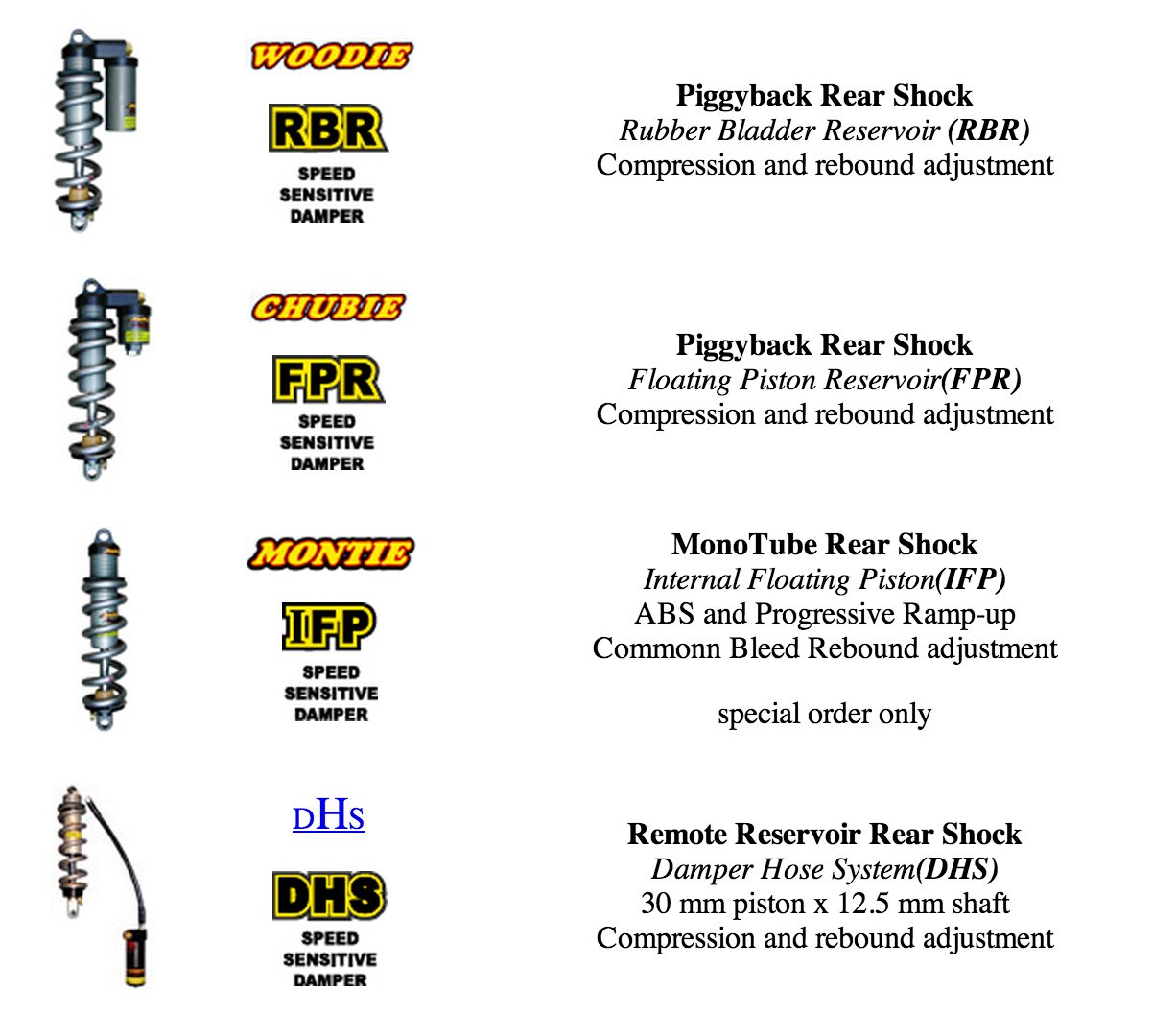

The Avalanche Chubie is one of four different rear suspension options manufactured by Avalanche. The Woodie, Chubie, and DHS are all comparable shocks, while the Montie is a less expensive option that does not feature externally adjustable high and low speed compression adjustments.

The reason for offering three seemingly similar shocks is to solve the fitment and performance problems that different suspension designs present. All three of the shocks share common components inside their main bodies, but feature different external reservoirs. So let’s talk reservoirs for a minute.

Reservoir Design

Avalanche has two different reservoir designs for their three reservoir-equipped shocks; the Woodie and DHS share a rubber bladder reservoir design, while the Chubie uses a floating piston.

External reservoirs are used to improve performance by offering a greater oil volume being pushed through more complex valving and providing more liquid mass to absorb heat and delay fading.

As a shock is compressed, the oil volume available in the main body of the shock is displaced by the shock shaft. That oil is pushed into the reservoir, compressing the gas there. In order to prevent foaming and cavitation caused by gas mixing with oil, the two are kept separate in the reservoir by either the floating piston or the flexible rubber bladder.

The bladder design (used on the Avalanche Woodie and DHS) has the best small bump compliance, since it has no seal stiction to overcome. This sensitivity makes it a great choice for riders that prioritize traction and initial stroke suppleness.

The floating piston of the Chubie enables the shock to be easily tuned for pedaling and end-stroke performance by making internal changes to the nitrogen pressure.

Speed Sensitive Damping

Avalanche uses speed sensitive damping (SSD) in all of their shocks. The “speed” being referred to here is the speed of the damping piston or shaft travelling in the oil, as opposed to the speed of the rider. The degree of damping is dependent on the shaft speed only, not its position in the damper at any given time.

This is in contrast to one of the common alternatives, position sensitive damping. In a shock featuring position sensitive damping, the compression damping force increases throughout the stroke of the shock—the damping is dependent on the position of the shaft in the stock, and independent of the speed of the shaft.

While position sensitive damping is great for making a shock resistant to bottoming, it can limit the shock’s effectiveness when the shock is already compressed halfway from small trail features and the rider hits a large rock or root in the trail—the damping force will be too great to allow the shock to reacte sufficiently.

With speed sensitive damping, that larger impact is absorbed in a controlled manner because it creates a high shaft speed and a corresponding response from the high speed compression damping (more on that below).

Position sensitive damping is usually used because of its simplicity, which makes it less expensive to design and manufacture. Speed sensitive damping circuits are typically more complex, and thus more expensive.

Lot of inaccuracies in this article but yeah, Avalanche products are generally really reliable, solid performers.

First, the Nomad does have a falling rate followed by a rising rate suspension through its suspension cycle. (“U” curve) However, the highest leverage ratio in the cycle is not in the “middle” of the stroke as you claim but rather at the ideal sag point (around 30 percent into the travel). The idea is to keep you at this point so the bike retains good small bump sensitivity but ramps up for larger hits. If you like, I can give you a X/Y axis chart showing this.

The idea of anything “wallowing” drives me nuts. The idea you need some sort of crazy expensive custom shock for your carbon framed VPP 2 frame is equally nuts. This bike rides great with a properly tuned Vivid, Monarch, Float X etc. The size of the shock has nothing to do with its “suspension valves being inadequate”.

One thing that is hard for people to wrap their head around is often fast suspension does not feel good. Throw a medium or firm compression tune RS product on there. I’d wager you’d end up with similar results when you are looking at the clock on a descent.

Again, not saying avy is bad but I’d hope you let your audience know there are a lot of other shocks that are equally as good of performers on that bike.

First, thanks for the considered response. Technically-focused dialogue is exactly what I hope a review like this can generate.

I certainly know the same plot that you are mentioning, and I agree with you that the peak leverage occurs at around 30% of the travel. I think the problem here is really one of semantics – I’m thinking of the middle of the stroke as 33-66% of the travel or so (probably weighted towards the front of that range too). I should have been clearer, but I do think that we are referring to the same range – that region of the stroke where the shock spends most of its time. I accept blame for not being sufficiently precise with my language.

The Santa Cruz Nomad MkII is a truly awesome bike with a stock shock. I should have emphasized that more, but the article is really targeted toward those users who find it because they are already considering purchasing a different shock to alter the suspension performance of the bike. I have owned my Nomad for around three and a half years and have loved it the whole time. First with the Monarch shock, and now with the Avalanche. Very few riders need a higher-performance shock than comes with the bike. However, if you are really pushing the bike and trying to ride terrain on which a DH bike wouldn’t be out of place, there is performance to be gained with a tuned Avalanche shock (or a properly tuned Vivid, RC4, or Double Barrel, etc.). The Avalanche is one of many options. It does come pre-tuned instead of relying on the user to tune the shock properly, and I feel that is a significant advantage. I used to think of Avalanche suspension as expensive too, until I actually looked into it. Yes, the Avalanche is more expensive than some other options, but it is almost exactly the same price as a stock Fox DHX RC4 shock or a Cane Creek Double Barrel. Factor in the durability, support, and tuning and it is actually a pretty good value.

The B tune on the Monarch 3.3 and 4.2 shocks I had is the spec’d tune for the Nomad. At high shaft speeds it felt reasonably good. If I were to move to the same Monarch shock with more compression damping, in exchange for more stable low-speed motion it would be more likely to pack up over larger impacts since it would be a fixed compression setting and not one with a blow-off that opens at higher shaft speeds. I’d love to try a Rock Shox or Fox product with a different tune if one were provided to me, especially a Vivid, or RC4, or Float X, or one of the other products that offers more complex damping and more tune-ability than the Monarch. However, since I had to purchase a shock, I preferred to put my money toward trying something different and supporting a smaller company. That decision has been rewarded with a great shock and truly incredible customer service.

A suspension manufacturer can definitely fit some awesome stuff in a small shock. The size however, can definitely have something to do with it. A larger shock usually has more oil volume, and more oil volume better deals with thermal fluctuations, and allows for larger damping ports/valves. Larger ports also tend to offer more reliable and tunable performance since they have a better ratio of cross section to circumference, reducing the magnitude of surface effects during fluid movement.

As far as descent times, you might very well be right, but I’m not a racer, so I wasn’t timing my descents. I ride fast, but purely for fun. So, instead of evaluating descent times, I was evaluating how enjoyable the descents were and for me that comes down to a combination of smoothness, control, and confidence. The Avalanche delivered on all three fronts, offering me decidedly better performance than the monarch shock that had come on the bike.

Thanks again for your comments.

Thanks,

Tom

Couldn’t agree more Tom, I bought a Chubie for my Nomad, what a difference it made, massive! i’m not exaggerating, going up, coming down, transformed the bike, fantastic product. I definitely found the fox shock wallowy in comparison(just what i felt).

all the best!

Darhyn,

So glad to hear that you are enjoying the Chubie!

Totally agree. Got an Avalanche shock for my Yeti SB66 and it was transformed. The complaints I and others had (as reflected in online reviews/comments) no longer exist. I have never felt a more composed ride; incredible climbing support while blissfully supple on everything from small chatter to big hits. Similarly, I have a Marzocchi 44 RC3 on the bike and love it, but wanted more mid-travel support. I got the Avy cartridge for the 44 and now it’s just perfect. Matt’s just wrong. Maybe his income depends on his supporting some mainstream suspension manufacturer. You know, those who produce suspension that “does not feel good” but which might produce a “similar result[] when [I’m] looking at the clock on a descent.”