Ochain R

Crank Compatibility: SRAM 3-bolt, SRAM 8-bolt, Race Face Cinch, Shimano Direct Mount

Chainring Options: 104 BCD 4-bolt chainrings; 32 tooth minimum

Blister’s Measured Weight: 168 g (Shimano mount, w/o chainring)

Bolted To: Kavenz VHP 16 V7, Geometron G1, Pivot Firebird, We Are One Arrival, Santa Cruz Bronson

MSRP: $450

Rimpact Chain Damper

Crank Compatibility: Shimano Direct Mount, Race Face Cinch, SRAM 3-bolt, SRAM 8-bolt, Hope

Chainring Options: 30, 32, 34, & 36 teeth

Blister’s Measured Weight: 238 g (Cinch mount, including 32 tooth chainring)

Bolted To: Kavenz VHP 16 V7, Geometron G1, Pivot Firebird

MSRP: £190 ($256 at time of publication)

DT Swiss Ratchet DEF DF

Compatibility: DT Swiss Ratchet DEG Rear Hubs

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- Ratchet DEG DF Kit: 41 g

- Net Weight Change: -3 g

Bolted To: Geometron G1

MSRP: $176.20 / €129.90

Intro

World Cup Downhill has become a game of marginal gains, so when the first Ochain device started showing up on racers’ bikes a few years ago, we had some questions about whether they’d see broader adoption. Fast forward a few years, including a notable acquisition of Ochain by SRAM, and chain damper devices have become far more commonplace than we might have initially predicted, both for pro racers and regular riders. Other brands have jumped into the fray as well, including Rimpact and DT Swiss, each with their own take on the concept.

What is it about chain damper devices that has led to a surge in popularity amongst professionals and weekend warriors alike? How effective are they? Is one design better than another? We had plenty of questions, so we spent several months testing devices from Ochain, Rimpact, and DT Swiss in search of answers — and now we’re ready with a roundup of what we found.

There’s also been a change in how the devices are described by their manufacturers. Ochain originally touted mitigating pedal kickback specifically, but now uses more expansive language about reducing drivetrain-induced feedback of various sorts, and Rimpact and DT Swiss have similar takes on the matter — and we’ll dive into all that, too.

A Word on Pedal Kickback & What Chain Dampers are Really Doing

So, what is pedal kickback? In short, on the vast majority of bikes, the distance that the upper section of the chain spans from the chainring to the cassette grows longer as the suspension compresses. Since the chain can’t stretch to accommodate that extra length, either the cassette has to rotate forward, or the chainring has to rotate backward to accommodate the extra length. In many circumstances, the cassette is free to rotate forward, and the chainring doesn’t need to move, but depending on a host of factors, that isn’t always the case. If the cassette (and thus the crank) has to rotate backward, that tugs on the pedals, delivering feedback to the rider and hampering the suspension’s movement. That’s pedal kickback.

[For a much deeper dissection of when pedal kickback does and doesn’t actually occur, check out the “Background” section of our review of the original Ochain.]

But pedal kickback isn’t the only potential source of drivetrain-driven suspension feedback. If you’ve seen a slow-motion video of someone riding fast through a rough section of trail, you’ve probably noticed how much the chain bounces around — it can be pretty dramatic. That movement can produce a sensation very similar to pedal feedback when the chain is bouncing up and down quickly, tugging on the crank and hampering suspension movement as it does so.

Design & Features

Ochain R

The Ochain R is their flagship product for non-motorized bikes (more on the other versions in a minute), and its overall form factor is very similar to that of the original Ochain that we reviewed a few years ago. The Ochain R takes the place of the chainring on a variety of cranks set up for direct mount rings (SRAM 3-bolt, SRAM 8-bolt, Shimano, and Race Face versions are available), and requires a 104mm BCD four-bolt chainring (sold separately).

Like all the Ochain variants, the R allows the chainring to rotate independently of the crank arm, within a limited window. A set of springs inside the Ochain R push the chainring to its most forward position (i.e., turning it clockwise when facing the bike from the drive side) when the chain isn’t under tension. From there, the chainring can rotate rearward up to 12 degrees to absorb pedal kickback and/or isolate the crank from feedback due to the chain bouncing around.

When you start to pedal, you have to rotate the crank until the springs compress and the Ochain R hits its internal stop before the wheel begins to be driven. The sensation is similar to that of riding a slow-engaging rear hub, albeit with a slight degree of springiness rather than being entirely free-moving. The Ochain R uses elastomers for the travel stops, so the engagement point is slightly cushioned, too, but it’s not noticeable once you have the Ochain R engaged and start pedaling — it feels entirely normal.

The main feature that sets the Ochain R apart from the original version is that the R features a dial to set the amount of movement, with options for 0, 4, 6, 9, and 12 degrees; the more basic Ochain N uses different-sized elastomers to control the range of motion (with 4, 6, 9, and 12 degree options), so changing the travel requires disassembling the device. Their functionality is otherwise identical. Ochain also offers eMTB versions of both the R and N, dubbed the Ochain S and Ochain E, respectively.

The “EASY” dial used to change the travel on the Ochain R takes up a little more space than the more basic adjustment on the Ochain N, which means that the Ochain R is only compatible with 32-tooth and larger chainrings; the Ochain N is officially compatible with 30-tooth ones. I did, however, run into clearance issues putting a 32-tooth Hope chainring on the Ochain R due to the bulge that houses the EASY mechanism; that same ring fits on the Ochain N with room to spare. A 32-tooth Race Face chainring fits on the Ochain R; the Hope ring also works if you space it inboard a few millimeters (i.e., narrow the chainline).

Rimpact Chain Damper

The concept and overall form factor of the Rimpact Chain Damper are very similar to the Ochain R, but they differ in a few key details. Like the Ochain R, the Rimpact Chain Damper mounts to various direct-mount cranks (SRAM 3-bolt, SRAM 8-bolt, Shimano, Hope, and Race Face versions are on offer), and the Rimpact Chain Damper uses a spring-loaded mechanism to allow for independent rotation of the chainring and crank arm in much the same fashion as the Ochain R.

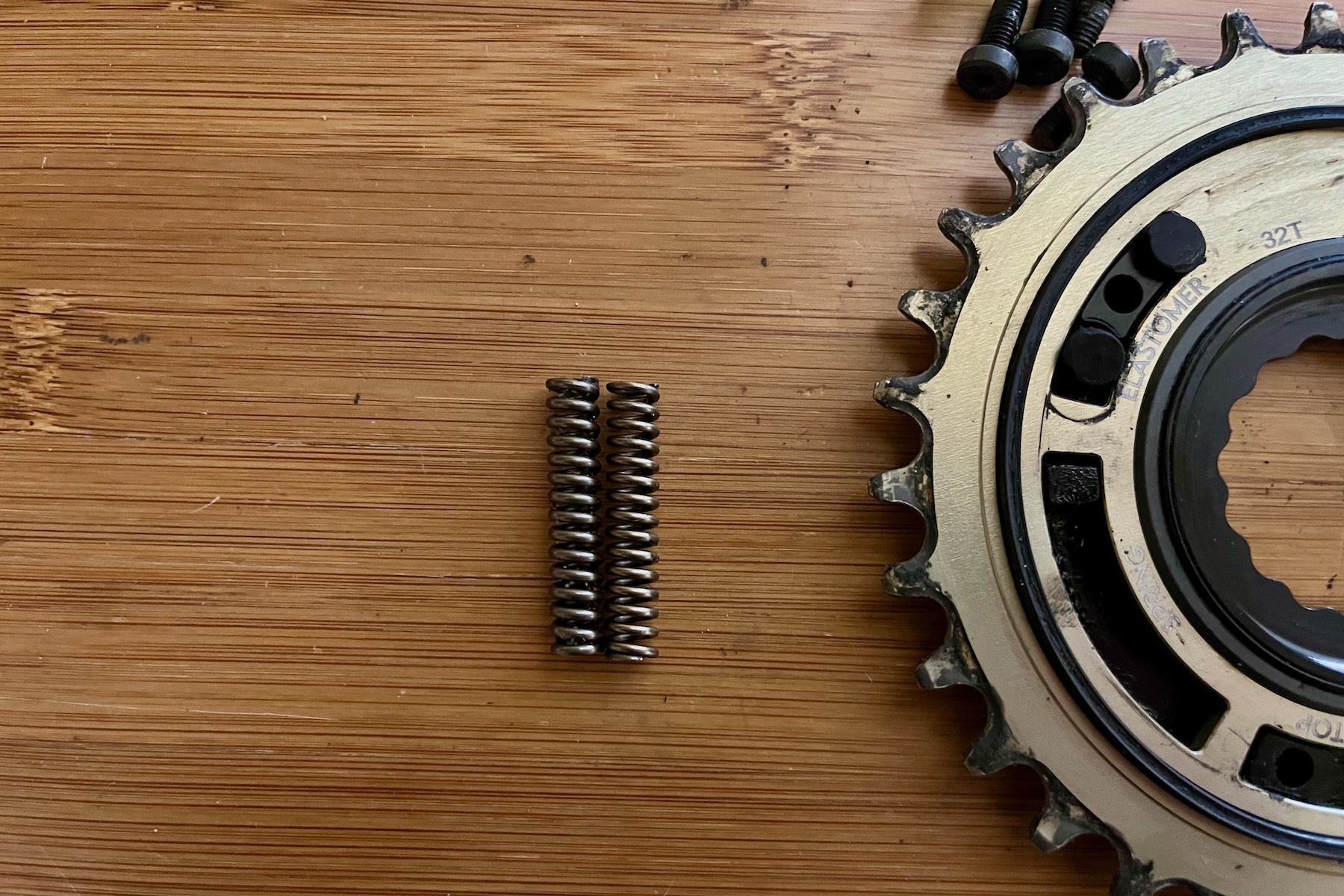

The first major difference between the Chain Damper and the Ochain R is that, while the Ochain R uses very light springs to make the chainring as free-moving as possible, the Chain Damper deliberately uses stiffer ones so that it can absorb more energy from the chain before bottoming out. Rimpact’s take is that the chain bouncing around is a greater source of feedback than actual pedal kickback, and they tuned the Chain Damper to address chain movement rather than optimizing it for kickback. The rotation of the Chain Damper is also fixed at about 9°.

The Chain Damper is currently only offered for non-motorized bikes, but an eMTB version is in the works.

DT Swiss DEG DF Kit

The DT Swiss DEG DF kit is meant to isolate the crank and suspension from chain forces in much the same fashion as the Ochain R and Rimpact Chain Damper, but it’s very different mechanically. Rather than adding rotation between the chainring and crank arms, the DEG DF mechanism frees the cassette to rotate forward and feed out extra chain to isolate the crank and suspension from chain forces.

The DEG DF mechanism is only compatible with DT Swiss Ratchet DEG rear hubs and is primarily offered as an aftermarket upgrade kit, replacing part of the freehub ratchet mechanism. DT doesn’t currently sell hubs or wheels with the Ratchet DEG DF kit installed, but has partnered with Reserve to offer DEG DF-equipped 350 hubs in their SL, HD, and DH wheels — both carbon and aluminum. Installing the DEG DF kit in an existing hub requires a proprietary tool from DT to remove the standard drive ring from the hub shell.

The standard Ratchet DEG rear hubs use a pair of toothed ratchet rings, which mesh with each other to drive the rear wheel forward under pedaling torque; the rings are pushed together by a pair of springs, and can slide in and out on a splined interface so that they can disengage and allow the bike to coast. The inner ratchet ring engages with a drive ring that’s threaded into the hub shell, and slides in and out on a splined interface with the drive ring; the outer ratchet ring does the same within the freehub body.

In either of the latter two configurations, when you start pedaling, the ratchet rings engage with each other per usual, but the inner one doesn’t start driving the wheel forward until it has rotated forward in the drive ring to the point where the splines on the two engage with each other. When you start coasting, the friction between the two ratchet rings means that the wheel (and with it, the hub shell drive ring) rotates forward until the splines on the inner ratchet ring hit the rear set of splines on the drive ring; at that point, the hub starts to push the inner ratchet ring forward, and the two ratchet rings click over each other as normal.

The ratchet rings have 90 teeth (for 90 points of engagement, or 4° between them), but the engagement is effectively slowed by whichever placement (0°, 10°, or 20°) it’s installed in within the hub. The effect is functionally the same as having a slower-engaging hub, with one key difference: the DEG DF system resets itself to have the chosen range of motion whenever you start coasting, whereas a conventional freehub has a random range of motion before it engages at any moment, from 0° up to the angle between engagement points (4° in the case of the Ratchet DEG internals).

In other words, the DEF DF system allows consistency in its degrees of freedom, where a traditional hub will be inconsistent. With the standard Ratchet DEG hub, the ratchet rings might have just clicked past each other at the moment that you encounter a bump, and you’d have the full 4° of movement before they engage again; they also might be on the brink of engaging, in which case you’d get 0° of movement. Most of the time, it’ll be somewhere in between. So, a “4°” standard hub mechanism actually provides an average of 2° of pedal kickback mitigation, but it ranges between 0° and 4° at random.

On-Trail Performance: Ochain R

Zack Henderson (6’, 160 lb / 183 cm, 72.6 kg): The Kavenz VHP 16 V7 is a high pivot bike with quite a bit of anti-squat, but the idler pulley helps to keep pedal kickback largely in check at a maximum of 6.5°. While that might make the VHP 16 a poor candidate for a chain damper on paper, I wasn’t so convinced that pedal kickback was truly the main sensation that these devices were solving for — and my experience with the Ochain R helped to prove that out.

Climbing

While the Ochain can feel a bit strange at first, I found the initially vague pedaling sensation to fade into the background after my first or second ride. When first setting out from a stop, you need to pedal through the free stroke of the Ochain device before it engages and begin transferring power through the chainring. While the elastomers in the Ochain provide a somewhat “springy” feel during the free stroke that can feel a bit odd while putting pressure on the pedal from a standstill, but it doesn’t require much force to push through the light resistance of the springs — a fact that is an important consideration relative to the Rimpact Chain Damper, but more on that in a minute.

The amount of free stroke is inherently related to the degrees of rotation selected via the Ochain R’s EASY system. The adjustment is easy to use despite the dial being difficult to grip with gloves on, allowing for easy on-trail adjustments. I initially wondered if I’d be tempted to lock out the Ochain R on days with more pedaling involved or when I wanted more response on the pedals, but I found myself treating the Ochain R’s adjuster as an initial guide for the feel that I was after, and then just leaving it in my preferred setting for most of the test period. While I tried all of the different settings, I ended up preferring the 9° setting for its descending performance while not feeling overly indirect under pedaling forces. While that might sound like a lot, a lot of that preference is down to the fact that the Ochain’s lag really only manifests at more uneven pedaling cadences.

On smoother climbs and while maintaining a relatively even cadence, the Ochain pretty much disappears after setting off from a standstill. Even light, consistent pedaling is enough to push through the elastomers to the hard stop, keeping the pedaling feel relatively direct. On technical climbs where pausing in the middle of a pedal stroke is sometimes required, there is a slight perceived lag in power delivery to the rear wheel, but I found it to be relatively insignificant for the types of trails I’m typically riding on my Kavenz VHP 16. That bike sees plenty of technical climbs, but I’m usually riding it when I’m prioritizing descending performance — which is where the Ochain shines. I would be a bit more hesitant to run something like an Ochain on my Trek Top Fuel, as pedaling performance and response are much bigger priorities on that bike.

David Golay (6’, 160 lb / 183 cm, 72.6 kg): The Ochain R feels a little odd when you start pedaling on it at first, but I quickly got used to it. Once the Ochain R is engaged (i.e., you’ve compressed the springs to the hard stop), the pedaling sensation feels entirely normal; the only slight quirk is in the first few degrees of crank rotation when you’re setting off from a standstill, since the movement of the cranks feels a little springy. Once you’ve got both feet on the pedals, the sensation mostly just feels like you’ve slowed down your hub engagement, but when you’re starting off and just have one foot on, the crank wants to spring back to its starting position, which takes a minute to get used to.

But, again, I quickly got used to it and haven’t thought about it since. The only real drawback to the Ochain R when climbing is the effective reduction in hub engagement when you’re ratcheting the pedals through technical sections. You could realistically set the Ochain R to the locked position for certain climbs and open it back up for the descents if you really want to, but it takes just enough fiddling that I doubt many people will bother.

Descending

Zack: The Ochain is intended to improve descending performance first and foremost, and on that front, it delivers — with immediately noticeable results.

As I mentioned earlier, my Kavenz VHP 16 has very little pedal kickback as compared to some other bikes, and it’s also already a rather smooth-feeling descender thanks to its planted rear suspension feel. Even so, my VHP 16 felt quieter from the first ride, both literally and figuratively — racket from the flailing chain was significantly lessened over a standard chainring setup, but there was also more perceived smoothness underfoot over repeated impacts. The suspension seemed to be a touch more reactive and supple over bumps of all sizes, but particularly medium and larger ones in rapid succession.

That quieter feeling underfoot was surprisingly encouraging when it came to riding faster. On relentlessly rough sections where things start to feel ragged, I noticed my bike feeling just a touch more composed, which in turn helped me feel like I wasn’t riding quite as close to the limit over repeated hits. That sensation helped faster paces feel slightly slower and more in control. It’s not a night-and-day difference, but the sense of a calmer chassis and more responsive suspension helps foster confidence at speed.

While I found the Ochain R to be effective in the 4, 6, 9, and 12° settings, I ended up landing on the 9° position as my preference for how it balanced pedaling and descending performance. The 6° setting, for example, felt a bit quicker to engage under power, but had the downside of introducing just a touch more feedback on really rough trails. In the other direction, the 12° position started to feel overly sloppy at the pedals, and while it did further mute feedback from the flapping chain, it didn’t make a big enough improvement in descending performance over the 9° setting to feel worthwhile for my bike and preferences.

David: On the way back down, the Ochain R makes a noticeable improvement to how planted and calm the rear suspension feels in some situations. Its effects aren’t particularly noticeable at lower speeds and/or on smoother trails, but as you start going faster on rougher sections of trail, there’s noticeably less feedback through your feet and appreciably less noise from chain slap with the Ochain installed.

The best way I can describe the effect is that it makes the bike feel calmer when things are getting hectic. There’s less noise, less pingy feedback through the pedals, and generally fewer distractions coming from the rear end of the bike, and less of a sense that the bike is getting unsettled for it.

Quantifying that difference is harder. I’d characterize it as being clearly noticeable, but not night-and-day dramatic, either. I also want to underline Zack’s comment that the Ochain R makes the most noticeable improvement over repeated high-speed impacts, where the bike gets unsettled (and, presumably, the chain is bouncing around more — I think the Ochain is muting a lot of feedback from chain movement rather than actual pedal kickback in those scenarios).

Personally, on my Geometron G1, I was happy just leaving the Ochain R in the 12° setting pretty much all of the time and not worrying about it. Granted, that’s a bike that I’m using predominantly for winch-and-plummet riding, and the bulk of that climbing is done on fire roads; technical climbing isn’t that bike’s strong suit, either. On my We Are One Arrival, I’ve mostly run the Ochain in the 9° setting to balance the uphill and downhill performance a little more, but running it at 12° is hardly the end of the world.

On-Trail Performance: Rimpact Chain Damper

Zack Henderson (6’, 160 lb / 183 cm, 72.6 kg): While quite similar to the Ochain in principle, the Rimpact Chain Damper feels more, er, damped, thanks to the stiffness of the springs used in the design. This tuning philosophy brings pros and cons to how the device rides.

Climbing

I did most of my testing with the lighter “Trail” springs installed, and despite their lighter feel, the Rimpact Chain Damper still feels stiffer in its actuation as compared to the Ochain. That means that the free stroke from putting pressure into the crank to where it engages and drives the chain feels heavier and consequently more noticeable — even with the lighter Trail springs, the Rimpact made itself a bit more known than the Ochain did while pedaling.

The Rimpact Chain Damper seems to have a comparable amount of rotation to the Ochain set in the 9° setting, and as I mentioned in the Ochain section above, there was a short adjustment period in getting used to the additional free stroke that the device brings, and how the drivetrain responds to initial pedaling input as a result. While the Rimpact provides a solid feel once the free stroke runs into the hard stop, I could get some strange oscillating sensations at times when the spring force overcame my pedaling forces at weaker points in my pedal stroke. On those rare occasions, I could feel the springs extending a bit and disengaging the Chain Damper from its hard stop, creating a lumpy feeling in how my pedaling input was driving the chain. This was only really noticeable at the top and bottom of my pedal stroke, where the pedals are just past the 12 and 6 o’clock, and power output dips a bit. I only noticed the feeling every now and again, and only at especially low levels of effort — and especially when I was tired.

With the lighter Trail springs, this was always down to uneven power delivery on my part, and paying attention to a smooth pedal stroke would resolve the feeling. With the heavier DH springs, though, I found that even focusing more on pedaling form couldn’t always eliminate the perceived oscillation as the stronger springs overcame my pedaling force at the weaker points in my pedal stroke. The stronger DH springs are quite a bit stiffer than the Trail ones, and I found that they could create the oscillation I described above pretty consistently at light to moderate power outputs. That sensation led me to prefer the Trail springs quite significantly for a bike that sees lots of pedaling — though as I’ll get into, those heavier springs have their place on the descents.

David: Like Zack, I found the Rimpact Chain Damper to introduce a significant hitch to my pedal stroke with the DH springs installed, and never got fully used to or comfortable with it. It’s not an issue under higher output efforts, but when spinning up an extended climb, I can feel the Chain Damper spring back at the dead zone in the pedal stroke (i.e., when the crank is roughly vertical), which means that I need to re-engage it with every downward stroke of the pedals. It doesn’t feel like it’s sapping power so much as it just makes my pedal stroke choppy; the sensation is distracting and not the most comfortable for me.

The Trail springs are light enough to remedy that drawback, though. I can detect a tiny hint of the same sensation if I’m pedaling very lightly, but the threshold for how hard I need to be going for the feeling to disappear is quite low, to the point that I find it to be a non-issue.

That said, it’s worth noting that I’ve mostly ridden the Chain Damper with clip pedals, whereas Zack has spent a lot more time on it with flats. I’ve got a few rides on the Chain Damper w/ Trail springs + flat pedals combo and still didn’t have any issues, but I can imagine that they might start to creep back in at the end of an especially long ride when I’m getting tired, and my pedal stroke starts getting choppy. It’s not an issue for me when clipped in, even when my elevation gain gets into the five-digit range (in feet), but it’s easier to maintain a smooth cadence with clips.

Descending

Zack: The Rimpact Chain Damper is more noticeable while pedaling than the Ochain R, but it’s also more effective at managing drivetrain-related feedback on the descents. With the lighter Trail springs installed, the Rimpact Chain Damper feels like a slight step up from the Ochain in terms of how effectively it keeps unwanted chain flail in check. Even on my idler-equipped Kavenz VHP 16, I found the Rimpact Chain Damper to quiet chain slap even more completely than the Ochain, with correspondingly less feedback through my feet as well. The result was an even more composed, calm-feeling chassis.

While the Trail springs are a slight step up from the Ochain in terms of feedback elimination, the stiffer stock springs crank the Rimpact Chain Damper’s effect up to another level. It’s the maximalist approach to chain management, virtually eliminating chain slap and providing the most damped descending feel, though with the drawback of the quirky pedaling traits that I described earlier. As impressive as the descending feel was, I can’t really imagine myself using the stiffer DH springs on anything other than a Downhill bike, where I’m often either hammering or coasting — the Trail springs felt like the more usable, everyday option for typical Trail and Enduro riding with mixed pedaling and descending time.

David: Fully co-signed. Rimpact is clearly onto something with the stiffer springs in the Chain Damper — even with less total movement (again, around 9°), the Chain Damper with the Trail springs mitigates noticeably more chain feedback than the Ochain R at 12°; running the stiffer DH springs only widens the gap.

Those differences feel most pronounced over repeated sharp impacts at speed, which suggests that the Chain Damper really is muting feedback from the chain bouncing around more than it’s tamping down pedal kickback in most real-world scenarios — you’re most likely to experience pedal kickback when the rear wheel is turning slowly, and the effect of the Chain Damper is most noticeable over repeated impacts, where the chain is presumably getting bounced around more dramatically than it is on one-off hits.

As is so often the case with these things, that feedback becomes a lot more noticeable when it goes away — most riders are probably used to a degree of chain feedback, but the extent to which the Chain Damper does away with it is eye-opening — again, especially with the DH springs. The sensation is very similar to that of the Ochain R; the difference is in degree, not kind. The Chain Damper is a bit quirkier but also has more pronounced performance upsides, and especially on a DH bike where climbing performance is out the window, it’s a very compelling option.

On-Trail Performance: DT Swiss DEG DF

David: Before we get to the on-trail performance of the DEG DF kit, it’s worth touching on its installation. Installing an Ochain or Rimpact Chain Damper isn’t really any different than installing a regular direct-mount chainring (which varies a bit depending on the crank in question, but is consistently straightforward with the right tools). The same can’t be said for the DEG DF, particularly if you’re doing so in a hub that’s been ridden with the standard internals first. Pedaling torque tightens the drive ring into the hub shell, and breaking it loose from a used hub can be extremely tough.

I wasn’t able to get the job done with the recommended technique of clamping the tool in a bench vice and turning the wheel for leverage, and had to resort to using a pneumatic impact driver (with an eight-point double square socket to drive the DT tool). That took care of things quickly and easily, but it isn’t an option everyone is going to have in their home tool kit. Be warned that installing the DEG DF might be a job for a well-equipped shop, even if you’re a solid home mechanic. The process isn’t complicated or hard in theory, but delivering enough torque to get it done can be tricky.

Climbing

The DEG DF internals feel exactly like having a slower-engaging hub while climbing — which, at the end of the day, is exactly what the kit does. Unlike the Ochain R and (especially) the Rimpact Chain Damper, there’s no discernible resistance in the engagement at all; as we’ve already covered, the Ochain R feels slightly springy, and the Rimpact Chain Damper does to a much larger degree (especially with the DH springs installed, but with the Trail ones as well). The DEG DF also engages with a solid metal-on-metal thud, rather than the elastomer-cushioned stop in the two crank-based options covered here.

The other big difference between the DEG DF and the crank-based options is that the latter designs have a constant amount of rotation at the crank before they engage, irrespective of which gear you’re in, whereas the movement that the DEG DF displays at the crank is a function of both which of the three settings you’ve chosen at the hub and the selected gear. The lower the gear, the more movement you get at the crank, and vice versa.

In the case of my Geometron G1 test bike, which I have set up with a 10-51 tooth Shimano cassette and a 32 tooth chainring, the rotation at the crank (from the DEG DF mechanism itself, setting aside the normal freehub movement that’s present regardless) is multiplied by 1.6 in the 51-tooth cog (so, 16° in the 10° setting and 32° in the 20° one) and 0.31 in the 10-tooth (3.1° or 6.2°), with the other ten gears landing somewhere in between.

The upshot is that the 20° setting feels notably slow to engage in the lower gears, and makes it a lot harder to ratchet the pedals and still put down power effectively. How much that matters is going to depend a lot on your terrain and preferences; I don’t mind at all when climbing fire roads and smoother trails, but it feels like a real limitation in more ledge-y, stair-step-y terrain in particular.

The 10° setting is a lot more manageable during technical climbing. It’s still slower to engage than the Ochain R or Rimpact Chain Damper in the very lowest gears (third gear is roughly equivalent to the 12° setting on the Ochain R), but it’s close enough to not feel like a huge difference — especially since ratcheting the pedals is more effective in higher gears, even without any of these devices installed.

Descending

The DEG DF provides an appreciable reduction in feedback through the pedals in the same sorts of descending scenarios where the Ochain and Chain Damper are most noticeable, but it’s the most subtle of the three. I’d chalk that up to the combination of the crank-based designs using springs to absorb some energy from the chain, and the fact that the DEG DF produces less effective movement at the crank in the higher descending gears (at least with the Ochain R in its wider range of motion settings; if you limit it to 4 or 6 degrees, the Ochain R feels a lot more comparable to the DEG DF).

The upside there is that the DEG DF also feels a bit quicker to engage in the higher descending gears, which helps a little when sneaking a pedal stroke or two out of a corner and the like. I frankly find that difference a lot less impactful than the change in engagement speed when climbing — as I mentioned earlier, I’m pretty happy running the Ochain R in the 12° setting most of the time — but it certainly doesn’t hurt.

One quirk I experienced a few times with the DEG DF is that it can produce a somewhat harsh-feeling clunk if it runs out of travel and engages the drive mechanism due to chain movement when descending. I only ever noticed it doing so a handful of times, and only when running the 10° setting while descending in a lower-than-average gear (i.e., near the middle of the cassette). My theory is that in the higher gears, the chain sits close enough to the chainstay (at least on the Geometron G1 I used for testing; this part will vary depending on the bike) that it can’t bounce around a ton because the chainstay protector limits its movement; in a lower gear, there’s more room for the chain to really whip around, to the point where I could feel the DEG DF hit its end of travel hard in a few instances.

Comparisons & Who They’re For

All of the chain dampers mentioned here are incremental upgrades — we’re talking marginal gains here, not paradigm-shifting performance upgrades. That said, they each go about their business differently, and there are some important considerations for riders debating the merits of one over the other.

Ochain R

The Ochain R is arguably the most balanced in its performance of the three options here. It produces less of a delay in pedaling engagement than the DT DEG DF (at least in the lower climbing gears), and feels more natural to pedal for extended stretches than the Rimpact Chain Damper (especially with the DH springs in the Chain Damper), while also effectively muting a fair bit of chain feedback in some situations. It’s also the most expensive of the three (at least if you already have a DT Swiss Ratchet DEG hub to install the DEG DF in), is limited to a minimum 32-tooth chainring size, and requires periodic maintenance to replace the seals, bushings, and elastomers as they wear out.

[Ochain’s official recommendation is to replace the elastomers after 75 hours of ride time and to perform a full service, including the seals and bushings, at 150 hours.]

The more affordable Ochain N functions identically to the Ochain R in a given range of motion setting; the N just requires you to open the device up and swap elastomers to change its range of motion, rather than featuring the external EASY dial. The external adjustability of the Ochain R is certainly handy for testing purposes, and some folks might like the option to lock it out for the occasional technical climb, but we doubt that most riders will change settings all that often.

That said, the Ochain N only comes with the 9° elastomer kit, and the other options are sold separately. The price of the Ochain N plus the other three elastomer kits (4, 6, and 12°) is the same as that of the Ochain R, so if you want to experiment with the different options, the price gap quickly evaporates. The Ochain N is also still compatible with 30-tooth chainrings, though, while the Ochain R is limited to 32 teeth and up.

Rimpact Chain Damper

From a pure feedback mitigation perspective, the Rimpact Chain Damper is the most effective of the three options here. It’s also a lot cheaper than the Ochain R, and is compatible with far more bikes than the DT DEG DF (at least without requiring a new rear hub at a minimum).

The biggest drawback to the Chain Damper is its tendency to introduce a hitch to the pedal stroke while climbing, especially with the stiffer DH springs installed. The softer Trail springs go a long way toward counteracting that sensation — enough to eliminate it for some riders — but it still might bother some folks, especially those who like to spin lightly and/or have a relatively choppy pedal stroke.

The sealing on the Chain Damper doesn’t seem to be quite as robust as that on the Ochain R (though cleaning and servicing are pretty straightforward), and it requires proprietary chainrings that are likely harder to find in a pinch, but as a maximalist option for mitigating the most chain feedback possible, it’s quite impressive.

DT Swiss DEG DF

The biggest upside to the DEG DF system is its simplicity: it doesn’t add any moving parts or wear items, and it’s 3 grams lighter than the standard Ratchet DEG internals. Both the Ochain and Rimpact Chain damper add something on the order of 150 grams (give or take a bit depending on the chainrings in question), and add some new seals, bushings, and elastomers that require periodic maintenance.

The drawbacks to the DEG DF are that it’s only compatible with DT’s latest Ratchet DEG rear hubs, it slows pedaling engagement in climbing-oriented gears more than the two crank-based options here, and it doesn’t mute feedback from chain slap quite as effectively as the other two (especially the DH-spring-equipped Rimpact Chain Damper). But if you already have a Ratchet DEG rear hub or are planning on getting one anyway, the DF kit still makes a noticeable difference. It’s also an especially low-risk option to try, since it can easily be locked out, effectively returning the hub to stock functionality.

Reserve offering the DEG DF as a no-cost upgrade in complete wheels is a great start, and hopefully DT expands its stock DEG DF offerings down the line, because apart from the cost and hassle of installing the kit as an aftermarket upgrade, there’s really no downside to it over the stock internals (with the slight asterisk that the DEG DF isn’t approved for eMTBs, but the standard DEG internals are only rated for up to 250 Watt drive systems anyway).

Bottom Line

The relevance of pedal kickback and the circumstances in which it does and doesn’t show up has been a hotly debated topic for years. It’s also probably a bit of a red herring — whether or not pedal kickback itself really factors into the equation in most situations, the chain bouncing around definitely produces unwelcome feedback when descending at speed, and all three of the devices here help mitigate that feedback to some extent.

They’ve also got their relative pros and cons, and there’s no one-size-fits-all “best” option across the board. They also probably aren’t the lowest-hanging fruit for a lot of folks looking to upgrade their bike’s performance — we’d prioritize stuff like brakes, suspension, wheels, and tires first. But all three of the options here make a real difference in how calm and settled the bike feels at speed in rough terrain, and that will make them a worthwhile upgrade for a lot of folks — especially aggressive riders on longer-travel bikes.