Modern Technology

As anyone who has ever shopped for outerwear knows, there are tons of waterproof, breathable options: GORE-TEX, eVent, H2No, Hyvent, Precip, Gelanots, c-change…the list goes on. So just what are we looking for here?

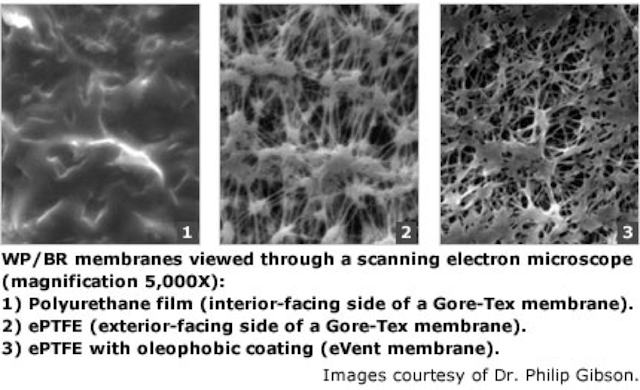

Waterproof breathable fabrics come in a few main derivatives: ePTFE based laminates, PU laminates, and polyester coatings. For our purposes, we’re going to split the technologies into three main categories: (1) GORE-TEX, (2) eVent and (3) the rest (PU laminates) as these technologies dominate the ski/snowboard outerwear industry. We’ve been pretty thorough with GORE-TEX, and for good reason, since it forms the basis for the majority of modern waterproof breathable (WP/BR) technologies. But let’s get to eVent and PU laminates.

eVent (pictured above in image #3) uses an ePTFE membrane just like GORE-TEX. eVent differs in the way it addresses the original GORE-TEX fouling issue. Instead of adding a whole new PU layer on the underside of the ePTFE, eVent uses an oleophobic coating over the ePTFE to keep contaminants away from the membrane. The chemistry is quite complex and out of the scope of this article (the application involves supercritical fluids, a very interesting branch of chemistry. Google it.) For now, we can think of this coating as slathering some paint on a strainer; the holes of the strainer are all still there, but the original material is now covered by this new coating. In the case of eVent, this prevents the membrane from becoming contaminated. Nice.

So it seems as if eVent has sidestepped the major breathability bottleneck of GORE-TEX, with fundamentally better technology, right? Well, in short, the answer is Yes, with a big BUT….We’ll talk about that later in the “Performance Ratings Debunked” section.

The third common waterproof/breathable technology is the PU coating. The same coating that GORE-TEX uses to protect their ePTFE can be used on its own to achieve very satisfactory results. The laminate ends up being significantly thicker than the layer GORE-TEX uses. However, it does not require diffusion across the ePTFE membrane as an added step in the water vapor transmission process. Most proprietary membranes like Patagonia’s H2No, and The North Face’s Hyvent, are derivatives of PU membranes. This technology is easy to manufacture, quite durable, and produces good results—a perfect recipe for product viability. Chances are good that if you have a piece of outerwear touted as waterproof/breathable, you have a PU laminate or coating in your garment.

DWR, Where the magic happens

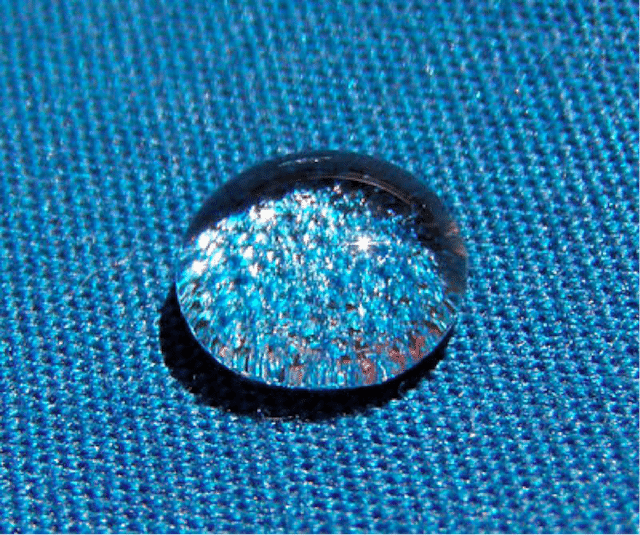

So you just bought a jacket that claims 20K waterproofing, and you’re stoked. You take it out on the hill, and at the end of the day, the jacket is heavy with water. Your brand new jacket has “soaked through.” Furious, you call the shop you bought it from and tell them what BS the product claims are and that this jacket isn’t waterproof at all.

But let’s look at what is actually happening.

We know that this jacket is probably a PU garment, which means it has a nylon face fabric bonded to the PU layer. We also know the actual waterproof and breathability characteristics come from the laminate and that the nylon face fabric is there for durability and support only.

The “20K” advertised by the manufacturer only references the performance characteristics of the laminate and has nothing to do with the nylon face fabric. The amount of water that the nylon face will repel has absolutely nothing to do with the performance of the laminate. So what actually happened to your new jacket?

The jacket you bought came equipped with a poor quality water resistant coating (WR), which allowed moisture to saturate the nylon outer fabric. Your jacket (in all likelihood) never actually leaked, and maintained its advertised “20K” waterproof rating, even though it was completely soaked.

The WR serves multiple purposes: it keeps your jacket from feeling damp, it maintains the breathability of the garment (a soaked through jacket has nearly no breathability), and it keeps your jacket considerably cleaner from water-based dirt and grime. A good WR is absolutely essential for a high performance jacket.

Today, manufacturers use what is known as a durable water repellent coating (DWR). This means that the coating won’t wear away as easily as a standard WR. Generally, a DWR will retain 80% of its “new” condition performance after 20 washes.

In short, the waterproof rating and the DWR have absolutely no relation to each other! Even so, people tend to confuse waterproofing performance with DWR performance. To the average (and even above average) consumer, the waterproofness of a material is judged by the DWR, not the laminate. It doesn’t matter how good the laminate is, if the DWR on the fabric is poor, you will not be happy with the performance of your garment.

Along with understanding the differences between laminates and DWRs, it is important to note that a jacket is only breathable as long as its DWR is working effectively. A soaked through textile has little to no breathability.

Companies like GORE-TEX and eVent use a proprietary DWR coating and spend millions of dollars in research to perfect this part of the product. In many ways, it is the most important piece of a waterproof breathable textile, and can make or break a piece of outerwear.

The bad news, however, is that it is almost impossible to know what you’re getting when you buy a product, because there is no standard for measuring the performance of the DWR.

Amazing article. Thanks so much. So enlightening.

Keep bringing it!

P

Freaking killer articles. All of them. Even as a seasoned gear shop employee and tech junkie, can always count on Blister to deliver the goods on beta, science, and the layman’s terms to tell the whole story.

Keep up the really really ridiculously awesome work.

jake

Thanks for the kind words fellas!

genius. i’ll never look at gore-tex the same way again. nice work man.

Such an interesting perspective on technical outwear, and an entertaining read!

Thanks for the great article!

Amazing article. Can’t believe I missed this when it came out. Blister FTW.

Wow. Technical yet totally accessible article. Great, great read for anyone looking to buy waterproof, breathable gear. I learned a lot & will try to spread the word about this article. Thanks!

Really in depth article, but really useful even for the non technical out there. You covered some great points. Time to go shopping for the right balance of tech in my new jacket! I’ve shared this on our Facebook, will be really useful to our followers.

Finally, an article that doesn’t reduce a complex issue to a couple of bullet points. Thanks!

Terrific article! Might I suggest for Outerwear 102 and article about actually dressing for skiing/boarding? How are the various layers supposed to be used? What do you guys wear for different conditions? Two layers? Three layers? How should you layer under a shell? Think would be a useful companion. Keep up the great work!

Great Article!

Was just about to buy 3L Gore pants… Questioned my choice (and the price)… Found your article… Read the whole thing… And just ordered the pants!

It confirmed my decision — also answered my long wonder about how the 20k/20g (etc) ratings compared to others and if they really could be trusted. Answer = no more board shop employees trying to sell me over priced claimed “technical” wear.

Thanks!

Hey Dan, glad I could help out!

This is a fantastic article. Where does Dermizax fall? I keep seeing the material in very high end Kjus ski jackets; is it simply a PU laminate? If so, I can’t imagine the performance would warrant the $1500 price. They claim incredibly high breath ability scores, but thanks to your article I now know to ignore them :) There also appears to be several versions of Dermizax. Is this material any good?

Most helpful article. Thank you Sam for the time and effort you invested to write this!

Great article, nice to see one of these that doesn’t spew the misinformation of water drop vs vapor molecules through holes stuff.

The one thing you didn’t stress was the effect of shell and liner fabrics on breathability of the total laminate.

Hey Slim,

That is definitely a huge part in the total breathability of any garment. A bit difficult to baseline, but certainly a huge factor. Thanks for your comment!

-Sam

stupendous and layman friendly article! it took me a few minutes to fully absorb (he he) all this ‘dry as a bone’ information to great effect. no ‘watered down’ or fishy patent references to get wallowed down in either! wish there were more ‘commercial’ PR folks who had the smarts to actually divulge facts, rather than foist their marketing jargon upon so many naive buyers!

So far what I’ve read on this site has been very useful, and I like the writing style. I don’t think I’m the only one around that is sick and tired of being treated as an imbicile, or worse, just a source of income by sometimes dishonest outdoor companies that are run by the marketing departments. Even companies like Patagonia, TNF, and others that started off right, by climbers and such, have gone far astray, letting the marketing departments and “the bottom line” affect their decisions.

Hell, Gore’s lies have killed people, hypothermic in their own sweat. How the f__k is that “keeping you dry”? Meanwhile they have made billions.

Good to see a honest, independent source of information. I hope you continue.

Got anything on Pertex Equilibrium, by chance?

Hey Alvin,

Pertex Equilibirum is a non-laminated (no membrane) fabric that acts like a very thin softshell. It is typically used in very lightweight garments and is not waterproof.

Like most non-laminate softshells, Equilibrium claims “weatherproof”-ness by using a high density weave on fabric exposed to the elements.

What makes Equilibrium a higher performance fabric than some others in this category, is the use of a denier gradient to facilitate breathability by capillary action throughout the fabric.

Basically, the inner layer of the fabric (against skin) is woven with a larger diameter fiber than the outside layer. This creates a driving force for capillary action out of the garment for breathability.

I hope that answers your question,

Sam

Yes, that is very useful information. Thanks a lot.

Is it just me, or is DWR way, vastly, overrated? I’ve had any number of pieces with DWR. Typically they stop working within minutes of a light rain, even when new. Of course it gets worse after even just a couple washings. And I buy good quality (in every other way) expensive stuff (Patagonia usually, also Arcteryx, Lowe Alpine, others)…I’ve yet to see DWR work properly. Ever.

DWR is a tricky thing to nail down. The performance depends on many things. When you have Patagonia claiming to put the same DWR on their M10 3L hardshell as a pair of casual pants, there is obviously going to be some performance differences.

In many ways, the fabric that the DWR is on is just as important as the DWR itself. Low density weaves, stretchy and high denier fabrics (like a lot of casual clothing) typically don’t have the same DWR performance as high density weaves on laminated fabrics.

Bottom line: DWR is essential to your hardshell, not so much to your “softshell” crag pants – and even then, performance varies wildly.

thanks, that makes a lot of sense. Even still, I haven’t had much luck with DWR on anything at all, honestly. My hardshell always wets out on the surface, and then doesn’t breathe, or even in cold weather sometimes becomes a sheet of ice-fabric.

It’s funny but just today I recieved email from a well-known, highly experienced outdoorsman who I happened to ask some of these questions to, and he told me he often uses an umbrella!

Others suggest those cheap plastic ponchos. That says a lot about the state of these “high tech” (and ridiculously over-priced) garments, I think. You can buy a lot of umbrellas and ponchos (or Hefty Bags!) for 600 bucks, eh?

You know, that is a great point to bring up. Depending on what you’re doing outside, often an umbrella or poncho is all you really need. Hardshells do NOT excel in rain, they just don’t work well for many reasons. If you’re in the rain and don’t need both hands, or aren’t sweating extensively, there are other options.

The reality of the situation is that 90% of the time you’re outside, you don’t need anything more than wind protection. In heavy, wet snows and rain — the other 10% — you need the protection of a hardshell. But most people (including me) go out in a hardshell almost everyday… Something I’ve been pondering a lot lately. Can a non-hardshell based layering system catch on in mainstream snow sports?

I had heard they already are popular in skiing and snowboarding, when the lodge is right there. I don’t believe a hard shell is all that necessary in snow for a few reasons: 1. snow takes time to melt, and brushes off easily, 2. snow is 90% air anyways, 3. in the cold, humidity is lower (i find things dry quite fast in the winter, IF they ever get wet in the first place, that is) 4. you don’t sweat as much in the cold, leaving the insulating and wicking layers with only external moisture to deal with 5. i had another one but forgot it right now kk

It seems to me, from experience of myself and others, and just logic, that the only truly difficult conditions to deal with (from a clothing perspective anyways) are sustained, cold rainy conditions, with temps above freezing up to the low 50s or so. And only then, really, when you stop hiking. As long as you are moving, you are generating plenty of warmth, and continuing the evaporative process. As soon as you stop either the rain that soaked in, or the sweat under a hard shell immediately makes you start chilling, and fast.

That’s my opinion, and I am going to start testing some soft shell combos when i get the chance in those kind of conditions. Honestly, how often do you get those kind of conditions? Not much, thankfully. But I plan to seek them out as soon as my new Equilibrium shell gets here! ;)

There is one garment that works well in chilly, wet conditions…the old school wool sweater, the think, airy kind (knitted i guess)…those things keep you comfortable in all kinds of conditions, and don’t over-heat readily. I’m sure the Llama ones in the Andes and the Yak ones in the Himilaya must just be superb, since those places are cold and people live up to 6000m above sea level.

Someone should really start researching this more and try to produce things of this nature commercially. I’m not sure what Sir Edmond wore, but I bet there was wool, maybe even Yak wool, involved…and clearly his porters were using that. Heck, they didn’t even have polyester in those days, I don’t think! :-D

Yes, if anyone knows of someone making Yak-wool sweaters, let me know. Maybe it could then be lined with micro-fiber and shelled with Pertex too…oh that would be great….heavy as hell, but great.

Brilliant article. It means even for an accomplished tailor/seamstress diy’ing a good shell that functions properly will take some thought and care. Tips on what to look for in terms of construction of a commercial garment would be great.

Many thanks!

Hey Rosanna,

I assume you’re looking for a commercial garment for inspiration in making your own? My advice would be that quality is less of an issue than simplicity.

If you’re making a 3L shell, precise patterning is essential, so much so that most major companies laser cut their fabric. The margin for error is tiny.

If you’re making a 2L shell, again, keep it simple! These garments can get extremely complicated!

Let me know if you have any other questions! I have commercially produced both 2 and 3L shells and may be able to answer your questions.

-Sam

Great article, one of the best i have ever come across. i just wanted to add a nit-sized comment – i have a Patagonia 2.5 layer ski jacket with the “H2No” membrane, and just a mesh liner that is not laminated to the membrane, but just hangs loose in the garment – I thought that was what was meant by the half-layer, but i see it’s used to describe a variety of materials and construction that is more than 2L but not quite a 3 layer build, either. so… Veritatem dies aperit… thanks again for the very informative article!

-Kevin

Fascinating! Thanks for the article. It’s so refreshing to have someone putting solid content out there. Most big publications could learn a lot from what you do. I’ve come to realize that soft shell jackets and pants with the right layer(s) underneath and a good or refreshed DWR finish are the most comfortable in all but the worst weather. Some trips are too remote or long to rely on soft shells but most are not.

Hey Greg, thanks for the kind words!

I definitely agree with your take on softshells. My go-to kit is all softshell. In 90% of the conditions I face, hardshells are overkill. We are keeping our eye on some companies making super light emergency hardshells (some that are under 5oz) that look interesting — throw them in your pack as a precaution and wear your softshell. Kind of a cool concept!

Can you elaborate on your standard kit a bit? I’m sure I’ve seen you write about / heard it on the podcast before but I can’t recall the details. Currently I’m skiing about 75/25 resort/touring and starting to figure out that the gear I need to be comfortable on the ascent needs to be lighter and more breathable that what I’ve been rocking. I’m wondering what direction to go for a complementary outer layer since I’ve already got a patagonia snowshot, which does seem fine for the down but is pretty bulky. I’ve got a handful of midlayers so I feel OK there. Would you go for a softshell here or look to upgrade the hardshell?

Hey Ari,

Unfortunately, I test so much gear that I never get to settle into a “standard kit” these days. That said, for 50/50 (or 75/25) kit, I would generally think like this:

Jacket(s): I think a midweight 3L hardshell with a roomier cut is generally a good, versatile option. When I say midweight, think 500-700 grams (size Medium). If you live in a drier area (like Colorado), then I would go with something air-permeable. On the coasts, I’d stick to a more protective shell. For mid-layers, I’m a huge fan of active insulation. The Patagonia Nano Air line has lots of options but it is far from the only active insulation on the market anymore — shop around and find something that fits well and is the right warmth for where you ski. For ski touring, I like to add a softshell to this kit. My current favorite is the Patagonia R1 TechFace, but that piece works best for very high output days. Something with a bit more weather protection is generally best for the average person.

Pants: I like to have a pant that is a bit more protective than my shell. I’m often kneeling/sitting/falling in the snow so the pant tends to get a bit more abuse. Again, I would go with a midweight 3L pant but I would prioritize large vents and fit/comfort over the “highest” tech fabrics.

Hope that helps!

Sam

Awesome, this is super helpful. I’m on the east coast and ski Colorado or Utah a couple times a year. I do think 3L shell is the right way to go but was maybe thinking of trying eVent. Might not be enough for an all around shell on those brutal VT days though.

Thanks for the comment.

Great article. I have been wearing an Arcteryx hard shell with a base layer and an atom jacket for skiing. Comfort wise, I’m plenty warm and never feel sweaty. The problem I’ve noticed, however, is that the hard shell is trapping moisture inside. I had been keeping my phone in the breast shell pocket and after a few runs, I noticed my phone was wet. Considering it was about 25 degrees at Deer Valley, I knew the moisture was coming from me. The base and middle layer were functioning as designed but the Gore Tex shell was trapping the moisture in. I guess I could have opened the pit vents but I never felt warm enough to want to open the vents.

I think switching to a soft shell product is going to make more sense.

Hi Sam, thanks for clever article. I’m in a market for kayaking drysuit. Kokatat use gore-tex and their drysuits are $1400. Company I found Level Six drysuits $800 use nylon and teflon membrane (and dwr and protective layer for teflon membrane). If gore-tex is made from teflon, will it be still better drysuit breathability and waterproofness wise? Many thanks!