Everything people say about this river is true. It’s difficult, committing, beautiful, and worth the epic drive to northern British Columbia.

But because I’d heard so much about the Stikine as the most challenging big water run in North America, it was virtually impossible to go into the trip with expectations that matched reality. Everything that I’d heard before paddling this river turned out to be true, just in ways that were different than I expected.

It all started at Bailey Fest, an annual gathering of kayakers on the front range of Colorado. After an awesome day of paddling on a front range classic, I was enjoying a couple of Oskar Blues brews around the festival grounds when Quinn Connell asked me what my paddling plans were for the fall. I’d been dreaming of heading up to the Stikine with my friends Sam Grafton and Ben Hawthorne, but it looked like our time off work wasn’t going to align.

I was bummed. And then Quinn said, “Dude, I would be down for a rally to the Stikine, except that my Jefe Grande just cracked and I don’t have another creek boat.” But as fate would have it, he won a Jackson Kayak Karma five minutes later in a raffle.

Suddenly, our trip was on.

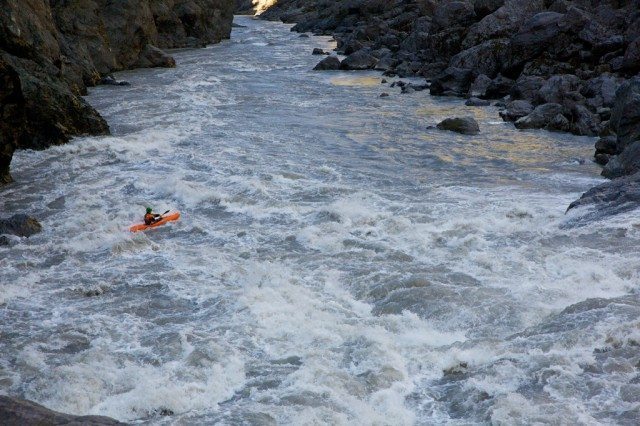

We knew the river was within our ability level, but our nerves were on edge since neither of us had run it before. With a healthy medium flow of ~330 cumecs, doing the run with just two people and without a “guide” is definitely not the norm.

I left Colorado Springs on September 2 to meet Quinn in Missoula, where we continued the 40-hour drive north in an old red Subaru that held up like a champ despite needing a bit of love along the way.

The first day of the drive didn’t feel real. Were we actually going to the Stikine? It didn’t seem possible that we would finally see the legendary river that we’d heard about our whole lives. On the second day of driving, we made it to Quesnel, BC—27 hours down, 13 to go. We slept for a few hours during a rain storm in a muddy pullout off a logging road, and woke up early to the sound of large trucks heading to work. Final day of driving. Things started to feel real. We were actually doing this.

Day 1: Waking up at the putin to sunshine and warm weather had us excited to get on the water. Flows looked stable, and the weather, with highs in the 70’s, was phenomenal. It was nothing like what I’d pictured; the legends had led me to imagine iron gray clouds and cold temperatures.

With perfect weather and flows, we decided to get on the water and worry about the shuttle later.

We reached Entrance Falls quickly and scouted it from the canyon rim. It looked big, but manageable.

This is when we learned our first lesson about scouting rapids on the Stikine: if it looks big, it’s huge and if it looks huge, it’s massive.

We both came through Entrance with huge smiles. The rest of day one went amazingly well. We found that almost all of the rapids were easily scoutable, something that surprised both of us. With two “passing” lines at Pass/Fail and clean runs of the infamous Wasson’s Hole, we rolled into camp at Site Zed feeling good about the next day.

Day 2: This was my favorite day on the Stikine. We elected to portage Site Zed, by far the largest rapid on the run, and continue downstream for a day filled with continuous but manageable whitewater. Almost everything was easily scoutable or boat scoutable.

The best part? Getting into camp that day. It was a beautiful beach with a large rock overhang to sleep under.

Camp two is amazing, but it shatters yet another legend about the Stikine. There’s a calendar stashed in a small crack within the cliff wall so that boaters can write their names next to the date they made their run. This summer, that calendar was crowded with names. Some people, like Ben Mar, had apparently been through the canyon many times in just a few weeks. As I lounged in the hammock that someone else had left behind at camp, I wondered about the changing nature of the river and its place in paddling lore.

NEXT PAGE: Day 3