Rescue Situations

Pulleys are always great pieces of gear to have either on your rack or in your pack. Alongside cord for making prusiks or autoblocks, pulleys are the central piece of gear in an emergency. This is where the Revolver holds its own.

If you have an injured second or simply a second who can’t unlock a difficult sequence (to choose just two of an almost limitless number of possible scenarios), you’ll likely wind up building some sort of mechanically advantageous hauling system. In such a system, friction and rope stretch can dramatically reduce the mechanical advantage, turning a 3:1 pulley system into a 2:1 or lower. In such a setting, anything that increases the efficiency of the rope system is a good thing, and the Revolver seemed like it could make a big difference here. After all, if you’re going to carry a pulley as part of your rescue equipment, it makes sense to integrate that pulley into a carabiner that you’re already carrying—thereby saving space and weight.

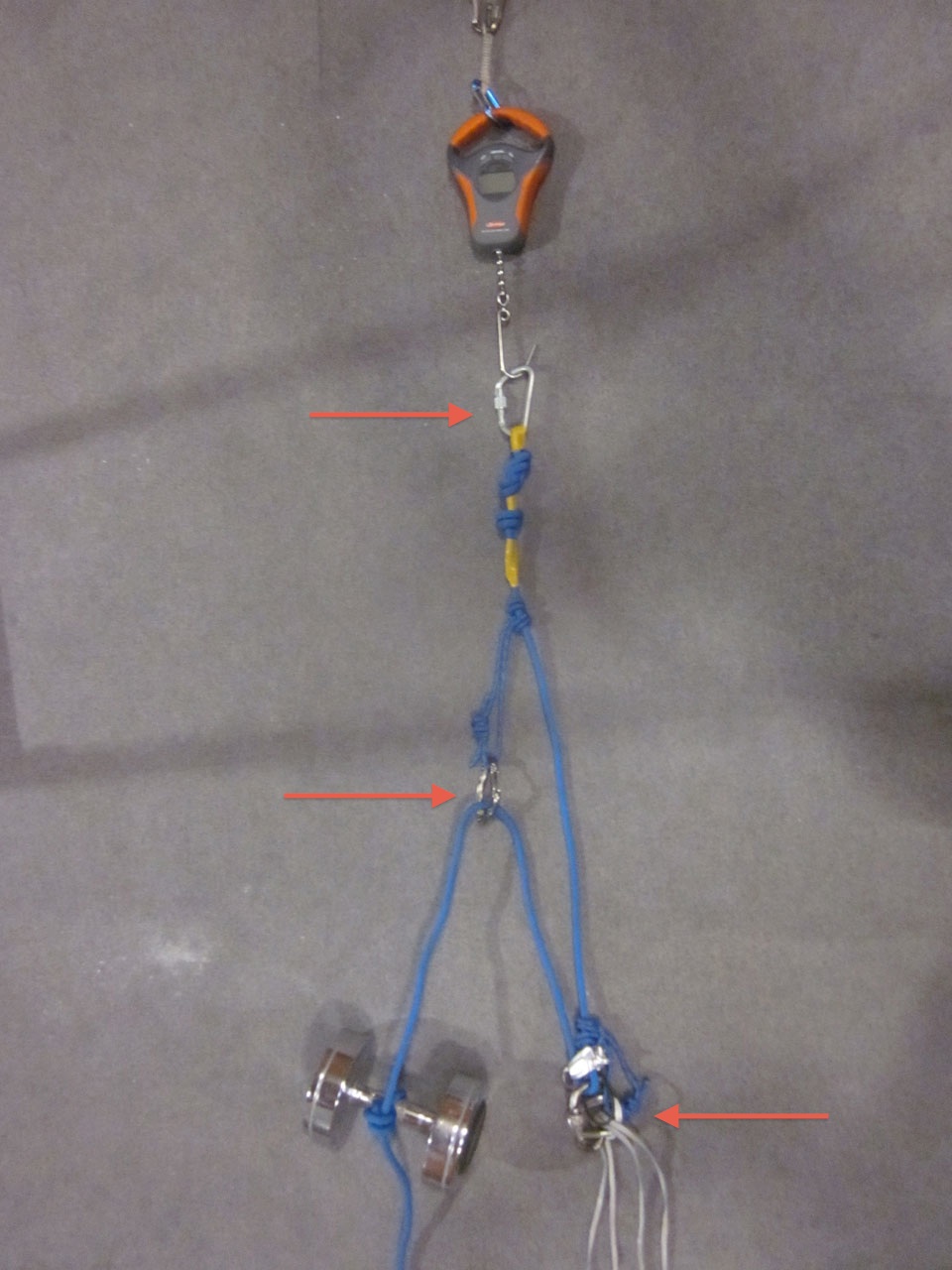

How much would carrying one Revolver improve your pulley, versus a regular, garden-variety carabiner? With the use of a spring-loaded strain gauge, I set to finding out. To do so, I set up a standard 3:1 with an ATC and a couple of prusiks. As a control, I set up the pulley system using all regular carabiners, hung a 30-pound weight from the hauling end of the rope, and recorded the force experienced by the strain gauge. I subsequently recorded readings with the Revolver as the anchor carabiner (the first pulley point) and again with the Revolver at the second pulley point.

First, a quick breakdown of the set up: though there are many, many options available to you for gaining mechanical advantage with your rope and other basic equipment, this 3:1 setup is among the most basic and is quite easy to rig. Though it isn’t required for the pulley to function, I included an ATC and prusik backup (as you would in real life to prevent any rope that you’ve pulled in to slide back through the system once you let go) to try and replicate a pulley system as I would build it in the backcountry.

I also want to note that while I strongly believe that climbers ought to know basics of both self-rescue (including basic haul systems and first aid), effective instruction on these topics is beyond the scope of this review. For a more detailed look at rescue techniques, I highly recommend the book “Climbing Self Rescue: Improvising Solutions for Serious Situations,” published by The Mountaineers, as an excellent starting point. Even these references books are, of course, inferior to undertaking proper instruction.

Back to the testing…

Lab Tests

In this arrangement, the strain gauge was located in the part of the system that would normally be whatever is being hauled (injured follower, etc.). Using the regular carabiners, the 30-pound weight exerted 46 pounds of force on the strain gauge. This represents a significant loss due to friction and rope stretch. With the Revolver placed at the anchor, 52 pounds of force was transmitted to the strain gauge. The reading held relatively steady at 53 pounds when I moved the Revolver to the second pulley point.

This represents a roughly 13% improvement in your hauling power by substituting in one Revolver over a regular carabiner in a 3:1 haul system. While this is actually less of an improvement than I was expecting, it is certainly enough of a difference to be noticed when pulling up a partner. It’s also worth remembering that these values were comparing a haul system with two regular carabiners at the apexs vs. one regular carabiner and one Revolver. Ideally, a haul system will have two pulleys to minimize friction. Considering the fact that comparable improvements in efficiency were achieved by both configurations involving the Revolver, I think it’s fair to expect a similar degree of improvement (beyond the 52 pounds seen in this case) by supplementing with a second Revolver or a proper pulley.

Bottom Line

My findings leaves me convinced that the Revolver deserves a place among my gear for “what if” situations. I am not sold on the idea that they’re even close to worth it ($26 for the non-locking wire gate; locking versions are available for even more money) for normal climbing situations.

It seems to me that if you are trying to get a handle on a terrible rope drag problem, you’re better off either (1) practicing more and refining your gear and sling usage or, (2) saving the money you would spend on a few Revolvers and putting them toward a set of double ropes (or even just one). Yes, a rope is more expensive, but a second rope offers so much more utility than simply reducing drag that it’s worth the extra investment.

For rescue situations, however, having even one Revolver is nice. And while it’s still expensive for a carabiner, it’s the same price as the cheapest pulleys on the climbing market. So if you’re looking to add to your rescue gear, why not just buy a pulley that you can use as a full-strength carabiner also?

Nice informative review! I wonder how much of a difference carabiner profiles make in terms of friction when pulling under load. A rounded HMS carabiner would seem to reduce friction whereas a regular carabiner with a more squared off profile would add friction. On the test without the pulley-biner did you use a rounded biner or more straight edged? I guess you can have the best of both worlds with this pulley biner.