Open Mic is the series on BLISTER where we invite various people in the outdoor industry to say what they have to say, and share whatever it is they feel like sharing at this particular point in time.

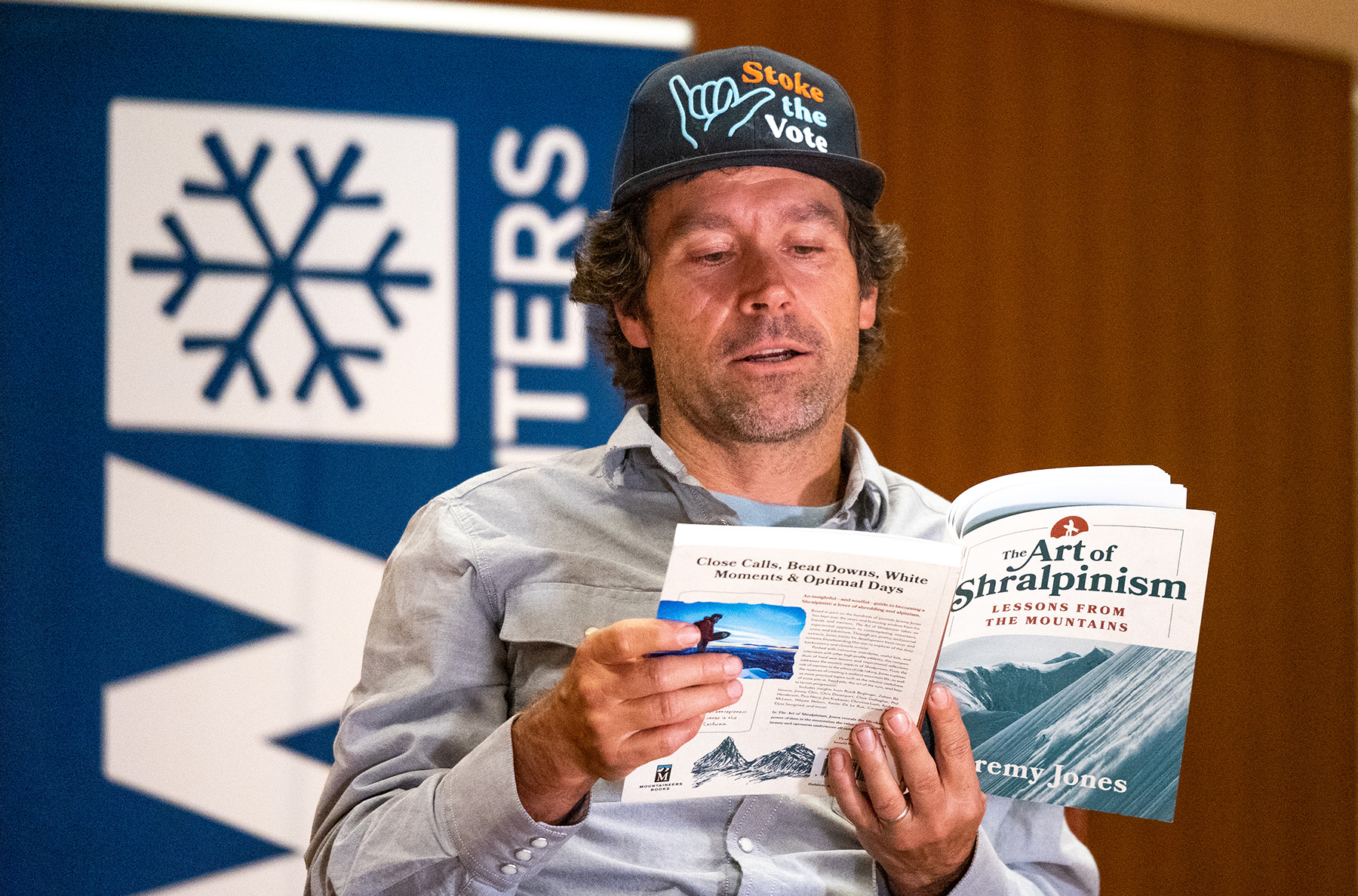

Today, we hear from Jeremy Jones, with an introduction by Jonathan Ellsworth:

INTRO

Few people in human history have carved lines down big mountains like Jeremy Jones. And while it’s one thing to be able to do that, it’s a whole nother thing to be able to communicate that experience through writing.

For the past several months, I’ve been working my way slowly through Jeremy’s book, The Art of Shralpinism: Lessons from the Mountains, published by Mountaineer Books.

Why slowly?

Because the sentences keep forcing me to stop. Frequently, they’re too rich or nuanced to blow through them without pausing to appreciate what’s going on, or to proceed without thinking through the point that’s being made. And this is true right from the jump, right from the opening pages. As you’ll see below, this isn’t a book that takes its time warming up and getting good.

Furthermore, I felt like the Prologue of the book is a perfect fit for our Open Mic series, so I reached out to Jeremy to see if he would be open to publishing those first pages of The Art of Shralpinism here, and here we are. But back to those sentences.

The act (and art) of skiing and riding — activities that millions of people are deeply passionate about — does not have the legacy of great writing that sports like running, climbing, and alpinism do.

And while I think it’s fair to assume that Jeremy’s intention was, first and foremost, to lay out more of an ethic or a way of life in this book than to (first and foremost) create some great work of literature that happens to have riding at the center of the story … there are numerous descriptions and passages in The Art of Shralpinism that hold up to the descriptions and passages of the writing of John Krakauer, Christopher McDougall, and even (dare I say it?) one of my all-time favorite authors — someone who, in his own way, was every bit as passionate about wild places and the outdoors — Henry David Thoreau.

If this seems hyperbolic, I submit just this one description — of several descriptions — that appear in the first pages of Jeremy’s book, published below:

“To understand when the portal opens so we can dance with the dragons has been my life’s focus.”

Read that again. Slowly.

To define the intention of your life with the words, To understand … when the portal opens … so we can dance … with the dragons…” that is topshelf writing about a peak experience.

It also avoids cliches entirely. Lazy writing falls back on old, worn-out phrases and images — e.g., This ski “floats like a dream,” and “carves like it’s on train tracks.” These are bad cliches that actually are impediments to thinking, that shut down more accurate ways of communicating an experience, and avoid the harder work of detailing exactly what a ski does or doesn’t do.

Great writing finds new vivid imagery that reveals the character of a thing or an experience. And I would argue that, if you’ve ever attempted to mitigate avalanche conditions and read the snowpack in consequential, big-mountain terrain, Jeremy’s description will resonate with you deeply — even if you never thought to articulate assessing risk and riding big lines in those terms.

I’ll leave it at just this one example. But there are several more in the opening pages of this book, and many more throughout the book.

And even if you aren’t particularly inspired by good writing, I’d still recommend this book if you spend time in the mountains, because its lessons might help keep you alive.

Finally, if you’d like to learn more about the insights, tactics, failures, stories, and principles of one of the greatest big-mountain riders of all time — alongside Jeremy’s own artwork and illustrations — then The Art of Shralpinism is also for you.

Here’s a taste. Take your time, see for yourself.

— Jonathan Ellsworth

Prologue — The Art of Shralpinism: Lessons from the Mountains

My mind is burning a hole through the blind rollover below me. What’s behind it? How steep is the face? Am I in the right spot? I stave off dry heaves with deep, controlled breaths. My snowboard is strapped to my feet, below me a 3,200-foot spine wall in Alaska’s Fairweather Range. The closest town is 50 miles away. The bottom of the face is guarded by a horizontal cliffband ranging from 20 to 200 feet tall. There’s no feeling in my toes, and my boots are loose because of frozen laces.

Yesterday afternoon, my riding partner, local Alaskan Ryland Bell, and I left the comforts of base camp with the hopes of being where I am right now, at exactly this moment. So much perseverance despite a sea of doubt, the efforts to cross the bergschrund and wallow and claw our way up the couloir. Topping out at twilight, we celebrated with a hug and a cheer before digging into the side of the mountain and getting some fitful sleep.

It is the moment of truth. I crank my bindings one last time, take a final deep breath, swing my board, and let unchecked gravity take me toward the abyss. One side of my brain screams, “Stop, stop, stop!” while the other fights back with “You got this! Hold the line!” I am playing a zero-mistake game of chicken with gravity and Russian roulette with the snowpack. The descent has played out in my head a hundred times. I have planned every turn, anticipated every blind spot and every type of snow texture, but now I let go. The world becomes quiet, my focus acute but not forced. The moment takes me.

An onlooker might call me crazy. An adrenaline junkie daredevil. But they don’t know the whole story. They don’t know that I’ve been sleeping under this peak for weeks building up to this moment. They don’t see the person who is in the perfect spot to dig me out if I do get into an avalanche. They don’t know that my life’s focus since I was fourteen has built up to my being here at this very moment. They don’t see the young kid who dominated amateur competition, got third in his first pro race at sixteen, and kept riding just fast enough to pay some bills, travel on the world tour, and almost make the Olympics. They don’t know I have two older brothers who taught me the fine art of dirtbagging and ski bumming, who called me at nineteen with the message “Sell everything, bring CLIF Bars and a sleeping bag, and get up to Alaska—we have a spot in our tent on Thompson Pass.”

That fateful afternoon in Alaska, when I followed my brother’s track in the waning dusk over the first blind roll of my life, it didn’t feel wrong, like I was willingly riding off the end of the earth to my death. I pushed through the fear and over the roll where the steepest, longest, most beautiful slope of snow lay below. In the pink light of the sunset my turns grew bigger and bigger, and I reached speeds I had only hit in a Super-G course. I was at ease and in total control.

Alaska’s grasp on my life was immediate. Things that had never been done before in the mountains elsewhere could frequently be done in Alaska’s stable, coastal snowpack that covered its steep, glacier-laden mountains. Within two years my brothers would start their movie company Teton Gravity Research, and my goal of being the fastest snowboarder on the World Cup circuit dissipated. My new compass heading was to push my snowboarding to new levels on the world’s best mountains and document it on film. Too many close calls too early on led to avalanche classes and a hyperfocus on risk management. We built a protocol—a method of mountain travel that limits risk—with the help of more experienced teammates, which enabled

us to consistently find the edge, tickle it at times, but never cross it.

To understand when the portal opens so we can dance with the dragons has been my life’s focus, although my approach has slowly evolved and morphed over time as I’ve gained more knowledge. When I was thirty, my career was about as solid as a pro snowboard career could be. My paycheck was based on being in snowboard movies and magazines, and I was in both, more than anyone else in the world. Most riders work all year for a single movie part, while I had just finished my most successful year ever, racking up a total of five parts. I was a master with a helicopter, where I could film a video part in three or four sunny days. But my body was breaking down, as was my mind. I had come to the edge of where I could take my snowboarding, as well as where I could take a helicopter or a snowmobile. That stagnation is the death of the brain and the antithesis of progression is a concept to which I’ve always held firm: I felt that if I wasn’t pushing the sport forward, then I should get out of the way so the next kid could.

The other major factor was what I was seeing happening to the mountains, specifically the effect climate change was having on them—shrinking glaciers, summit rainfall in January, low-elevation resorts struggling to open. These changes meshed with what the scientific world had been warning us about. It did not sit well with me that my personal carbon footprint was negatively affecting the very thing my life was centered around: snow. At this time I turned toward “foot-powered” snowboarding and riding the best line of my life in the backcountry. And getting there under my own power.

I wrote about this change of perspective in my journal in 2007: “We were like big game hunters equipped with spotlights and rifles. It was time to grab the bow and arrow and camping gear—time to give these mountains the respect they deserved. Time to sleep under these dream lines, to learn from them and live with them. Then when the time became right, to tiptoe up them and snowboard back down.”

With a whole new crew of riders and filmers, I set out to make my first foot-powered snowboarding film, Deeper, which I thought might be my last film ever. A year into filming, with hardly a thought, I left my sponsor of nineteen years, Rossignol, and started Jones Snowboards because the splitboards I needed to achieve my new goals didn’t exist—I had to design my own.

Two years into backcountry filming, Ryland and I are poised to drop into the biggest spine wall of our lives. We had climbed and bivied at the top of the face, waiting for morning to come. Picking up speed, I find my flow. Even though I’m in total control, there is no way I can stop. The

slope is too steep and each turn creates small sluffs that build into small avalanches. These are predictable slides, and depending on my appetite, I mix it up and play with them like a surfer plays with a wave. We call this “sluff management.” But my internal Spidey sense knows that I have monster sluff building above me and to my left. Moving at the same speed as the sluff, I feel the weight starting to grab the tail of my snowboard. An essential rule in sluff management is to never sluff your exit—or at least get to your exit before your sluff does or find a

safe spot to pull up on an “island of safety” while the sluff cascades through your line. This is poor sluff management, something I try to avoid at all costs.

My exit is to my right, off the smallest part of the cliff. I purposefully do not ride above it until the end of my line in order to leave it clean. This means that the majority of my line is over the biggest part of the cliff. Cut over too early and I sluff my exit, too late and I’m dragged off a huge cliff and get seriously hurt or worse. As much as I wrestled with this in the days leading up to my line, my mind is totally free of any such thought. I bounce down the spines and dabble with a rare “white moment.” Everything is quiet, despite the rush of my sluff and the wind. Hundreds of micro-decisions and adjustments are being made, but I give them no thought. My mind and body are one. I perfectly position myself over my exit air just as my sluff reaches it. Together we fly through the air like I am jumping a snow waterfall. The landing is soft and steep, and although it is now partially hidden from the explosion of my sluff off the cliff, I stomp the landing. Coming out of the smoke, I wait a few seconds and then lean into a few celebratory powder turns before straight running toward the glacier valley below. My body shakes. Uncontrollable

screams are followed by sobs and tears.

Ryland and I have just ridden one of the best lines of our lives, all under our own power. A huge achievement for the time. That line will stay with me forever, but all I can really think about is that I will see my infant daughter and wife again. That I will live to ride another day. The sad truth is that too many of my friends, heroes, and mentors have not lived to ride another day.

What follows in these pages are the people and experiences that define me. I’m not proud of every decision I’ve made in the mountains, but often we learn the most from our mistakes. The trick is not dying in the process. I’m not better than those who’ve fallen to the mountains. I’ve tried to be honest about the risks, stack the deck as much as possible, pick the right time to walk on the moon and with the right plan and the right people. I’ve tried to be present enough to know when the mountains lie down and welcome you, or when the danger scale tilts too far in the wrong direction and it is time to back off.

At the heart of this passion is the ability to push through significant mental and physical barriers when the struggle is grand but also to have the wherewithal and awareness to recognize nature’s subtle signs that turn a green light to red in an instant, requiring you to abandon one of your life’s greatest goals. This mix of gusto and humility, fearlessness and fear, grit and sensitivity, requires a deep understanding of who you are as a person at your innermost core, as well as an intimate connection with nature and your partners, plus a deep understanding of the behaviors, characteristics, and subtleties of all things snow. This is the Art of Shralpinism.

About Jeremy Jones

Jeremy Jones is an author, climate activist, founder of Protect Our Winters, and one of the greatest big-mountain snowboarders of all time. For more from Jeremy, check out our Blister Speaker Series video and podcast with him.

Damn. Thanks for sharing this.