When Ibis Cycles founder Scot Nicol sold the brand in 2000, its new ownership claimed it would show the cycling world “how to run a company.” Within 20 months, they’d driven Ibis into bankruptcy. In 2005, Ibis re-launched on the belief that bike-building should be as much about fun and creativity as it is about the latest bike technology. Seven years later, that belief remains intact.

When Ibis Cycles founder Scot Nicol sold the brand in 2000, its new ownership claimed it would show the cycling world “how to run a company.” Within 20 months, they’d driven Ibis into bankruptcy. In 2005, Ibis re-launched on the belief that bike-building should be as much about fun and creativity as it is about the latest bike technology. Seven years later, that belief remains intact.

It is the winter of 1980-1981, and Scot Nicol is feathering the end of a bronze rod along the joint between two steel tubes in a garage in Mill Valley, California, north of San Francisco. He is holding the rod in his left hand while, with his right, he keeps a blue flame about six inches away from where the steel and the rod meet, causing the bronze to melt and fuse the tubes together. Watching him is Joe Breeze, who along with Charlie Cunningham is acting as a mentor to the young Nicol toward the end of his apprenticeship in mountain bike building.

Nicol is in a good spot. Not only are Breeze and Cunningham masters of the craft, but each has been pivotal in the early development of the mountain bike. In 1977, Breeze began building his own bikes in Marin County, bikes that he called “Breezers.” Each frame was made of 4130 cro-moly steel and, collectively, they were the first off-road bicycles ever made. Two years later, Cunningham was the first to build aluminum off-road frames.

While apprenticing under Breeze and Cunningham, Nicol is also living with Steve Potts, an original “Repack” Downhill racer, an early incarnation of today’s downhill mountain biking. Potts and Cunningham, along with builder Mark Slate, would later go on to co-found Wilderness Trail Bikes, a key innovator in bike components.

Every day on his way to work with Breeze and Cunningham, Nicol rides from Potts’ house over Mt. Tamplais—terrain that many consider to be the birthplace of the sport—to the garage in Mill Valley, and back.

But it is Breeze and Cunningham who will have the greatest effect on Nicol. Although they are both early masters of bike construction, they each have a very different approach to bike building. Breeze looks to tradition, and excels in detailed craftsmanship and doing things the way they’ve always been done; Cunningham questions everything in a constant effort to improve every detail of his bikes.

When Nicol goes on to found Ibis Cycles later in 1981, his approach to bike building is a marriage of Breeze’s and Cunningham’s styles. His Ibis frames are fillet-brazed steel (like the Breezers) but with a shorter wheelbase and more compact frame (like Cunningham’s aluminum bikes). The result is a bike that feels more light and agile, a theme that is reflected in the company’s name.

When Nicol goes on to found Ibis Cycles later in 1981, his approach to bike building is a marriage of Breeze’s and Cunningham’s styles. His Ibis frames are fillet-brazed steel (like the Breezers) but with a shorter wheelbase and more compact frame (like Cunningham’s aluminum bikes). The result is a bike that feels more light and agile, a theme that is reflected in the company’s name.

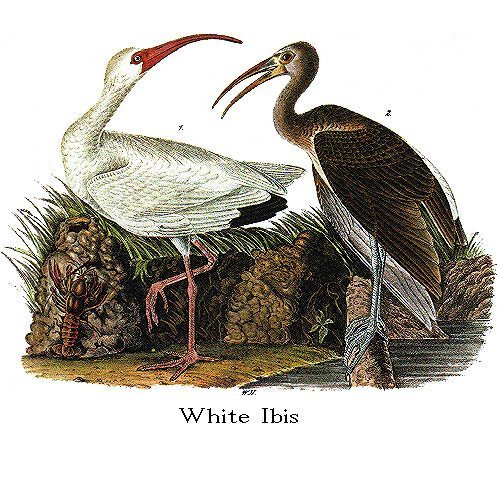

“Traditionally, a lot of bikes were named after birds,” Nicol says. “I had an Audubon bird encyclopedia that had a beautiful photograph of an Ibis, and I named it Ibis because I liked the look of the bird.”

As a wading bird similar to a heron or an egret, a walking ibis resembles something like a football on toothpicks, but Nicol is quick to note, “We prefer to think of it more in its flying mode.”

Early on, Ibis made clear that it was not afraid of risk. In 1988, Ibis built four frames out of NASA-grade carbon fiber, which Nicol, channeling Cunningham, calls “a great experiment.” The carbon was so expensive that each tube cost hundreds of dollars.

“Most of that material ends up in space,” says Nicol. “We were definitely pushing the envelope, [and] the technology we had wasn’t quite developed. The manufacturing technique [eventually] changed to build bicycles.”

Six years later, Nicol would write a seven-part series for VeloNews called “Metallurgy for Cyclists,” whose fifth installment was titled “Carbon Fiber Boasts Tremendous Potential.”

Along the way, Ibis found humor in the rest of the industry’s high-minded seriousness. (Biking is first of all fun, remember?) So Ibis gave their bikes names like the “Moron,” a response to Columbus’ “Genius” and Ritchey’s “Logic”—both steel frames with more material on the ends—and the “Hakkalügi,” to Kona’s “Haleakala.” (If you don’t get it right away, just say “Hakkalügi” out loud a few times.)

Then came the turn: in 2000, for reasons he prefers not to discus, Nicol sold the company. Ibis’ new ownership, which came from the biotech industry, claimed it would show the cycling world “how to run a company.”

Twenty months later, Ibis was bankrupt.

Its headstone read: 1981-2002.

Nicol, however, would have it read 1981-2000, since he doesn’t consider the 20 months after the sale to count. Those new owners were “just impostors,” he says.