Editor’s Note:

Welcome to our first Open Mic piece of 2024. The piece was actually written by Sander Hadley more than a month ago, on December 5th. But an extremely busy end of 2023 — coupled with an extremely busy start to 2024 around here — means that we are only publishing this piece now. But, for reasons that I think will be apparent to those of you who have been seeing the snow reports around a number of places across the western U.S. (at least), well, it sort of underscores what Sander is getting at here. Please enjoy.

— Jonathan Ellsworth

Open Mic is the series on BLISTER where we invite various people in the outdoor industry to say what they have to say, and share whatever it is they feel like sharing at this particular point in time.

Today, we hear from Sander Hadley:

I’m writing this on December 5, 2023, and what I really want to know is:

Where is the snow?! Come on Mother Nature!

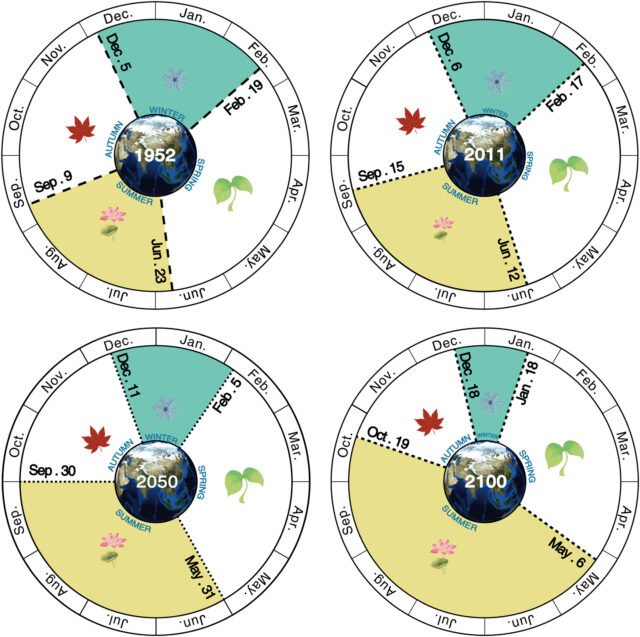

Did you know that, despite the snowsports industry’s best marketing efforts, winter is astronomically defined as starting on December 21st, and ending on March 19th?

Astronomical dates are based on the Earth’s relation to the sun — the way that the Earth orbits the sun, as well as the Earth’s axial tilt. During the North American winter solstice, the North Pole is tilted farthest away from the sun, which makes for the shortest day of the year, and the longest night of the year.

The other system for defining seasons is meteorological.

Based on calendar months and temperature patterns, the meteorological system is used to collect data and monitor the climate. It divides up the 12-month year into four equal parts: winter (December – February); spring (March – May); Summer (June – August); and fall (September – November). Winter is the coldest, and Spring is the warm-up period that follows. Summer marks the peak of high temperatures, and fall marks the cool down from summer.

If you’ve been a skier or snowboarder for more than a few years, you know that winter predictions from things like the farmer’s almanac or how high the beehives are in the trees are about as accurate as drawing straws.

Some other theories focus on how thick onion skin is during harvest; how bushy squirrel tails are in the fall; and how foggy it is during the month of August.

Then, there are some actually scientific indicators of snowfall, like ocean temperatures, or volcanic eruptions that disturb atmospheric layers.

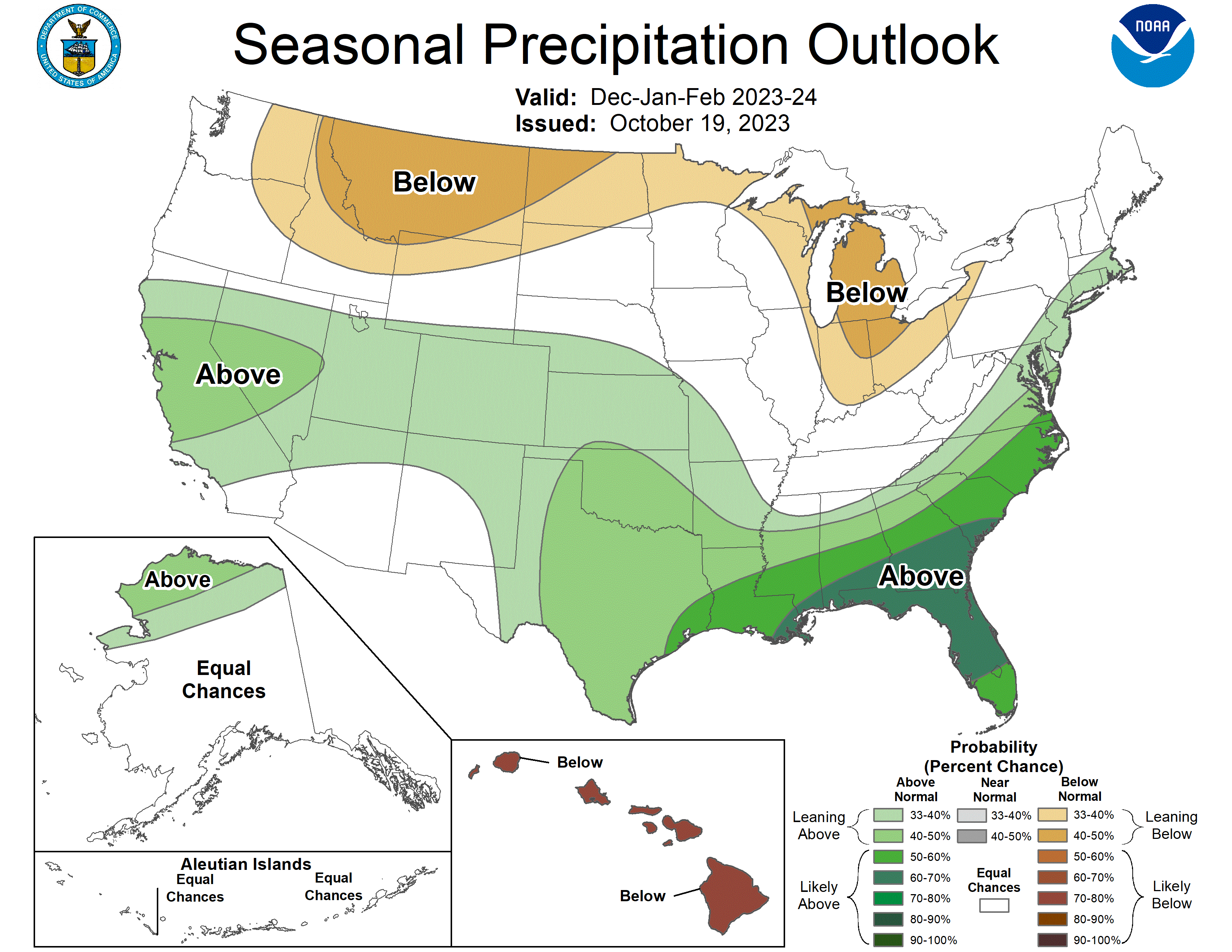

In El Niño (“little boy”) years, trade winds weaken, and warm ocean water is pushed against the west coast of the Americas. The warm ocean water forces the jet stream further south than its neutral position, which leads to wetter conditions across the southern U.S., and leaves the northern U.S. high and dry, with mild temperatures and low precipitation.

La Niña (“little girl”) is the opposite of her brother: stronger than normal trade winds and warm water pushed toward Asia lead to the upwelling of cold, nutrient-dense water in the western seaboard. This combination pushes the jet stream further north, leading to drought conditions in the southern U.S., while northern parts see cooler temperatures and higher precipitation amounts.

As for skiers, most of us end up sounding like Charlie from “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” combining half-baked theories and actual scientific conclusions into a winter forecast.

My hometown of Pocatello, Idaho, sits right on the edge of the normal jet stream in the southeast corner of the state. So even in a La Niña year, we might end up with the dry, southern end of the stick or vice versa. Add in the volatility of a changing climate, and weather predictions get even murkier.

The planet is heating up. November marked the sixth straight month of record-high temperatures across the globe. This is causing big changes, and the seasons are shifting. If we continue to emit carbon at our current rate, by the year 2100, summer will extend to six months of the year, while winter will dwindle to just two.

Think of the implications for agriculture, animals, and humans, let alone … our snowpack.

With all of these factors leading to increased volatility of weather, shouldn’t we be grateful for any amount of snow the spiritual mother deity in the sky gives us? After many years of all-too-high expectations not being met, I stopped checking the early season forecast. Sure, I’ll look at a weather app so that I know whether it’s going to be sunny or precipitous, but getting all bent out of shape over a discrepancy of a few inches of snow doesn’t help me this time of year when I’m already getting FOMO from social media.

A friend recently asked me how much I thought it was going to snow before a big forecasted storm. “I’ll believe it when I see it,” was my answer. Maybe a bit superstitious, I try to manage expectations when someone near me says something along the lines of “Did you hear? Lots of snow forecasted.” Asking questions like, “Where is the snow?” and antagonizing mother nature makes you a Simpsons cartoon.

Maybe think about lowering those expectations as a way to scrape together some happiness. Do your best to not compare this year to past seasons, especially if you live in the western U.S. Because things are only going to get more volatile and less predictable.

My home mountain of Pebble Creek Ski Area usually opens around Christmas and closes around the end of March, so by the astronomical definition, I am skiing all winter long.

So what is there to complain about? I’ll continue to play it where it lies here at home until I can’t anymore. Let’s appreciate what we have. And let’s be patient.

About Sander Hadley

Sander is a professional skier from Pocatello, Idaho. To hear his story in his own words, listen to episode 207 of the Blister Podcast.

Sources

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina.html

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2020GL091753

https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/old-man-yells-at-cloud

https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/pepe-silvia

https://www.almanac.com/content/first-day-seasons

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=123684