Intended Use: XC to DH; any bike where you want to change your seat height quickly.

Rider: 5’9”, 150 lbs, prefers downers to uppers.

Bike: Pivot Firebird on lots of sloppy spring rides

Test Locations: Western Montana. A little bit of everything—long climbs, smooth flow, wet roots, big drops, the occasional patch of snow, and most everything in between, with an emphasis on cold and rainy.

Test Duration: About a month

MSRP: $299

[Editor’s Note: We’ve updated this review, which originally ran June 25, 2012, with a section about the GravityDropper post’s long-term durability.]

GravityDropper posts are not new—they’ve been around for longer than any other dropper post currently on the market, vintage Hite Rites notwithstanding. The Turbo is the “newer” version of the post, but has still been available for considerably longer than most of the alternatives. When much of the competition is trending toward more complexity, however, the GravityDropper remains resoundingly simple. A lack of hydraulic gadgetry and pneumatic whiz-bangery isn’t necessarily a bad thing, though.

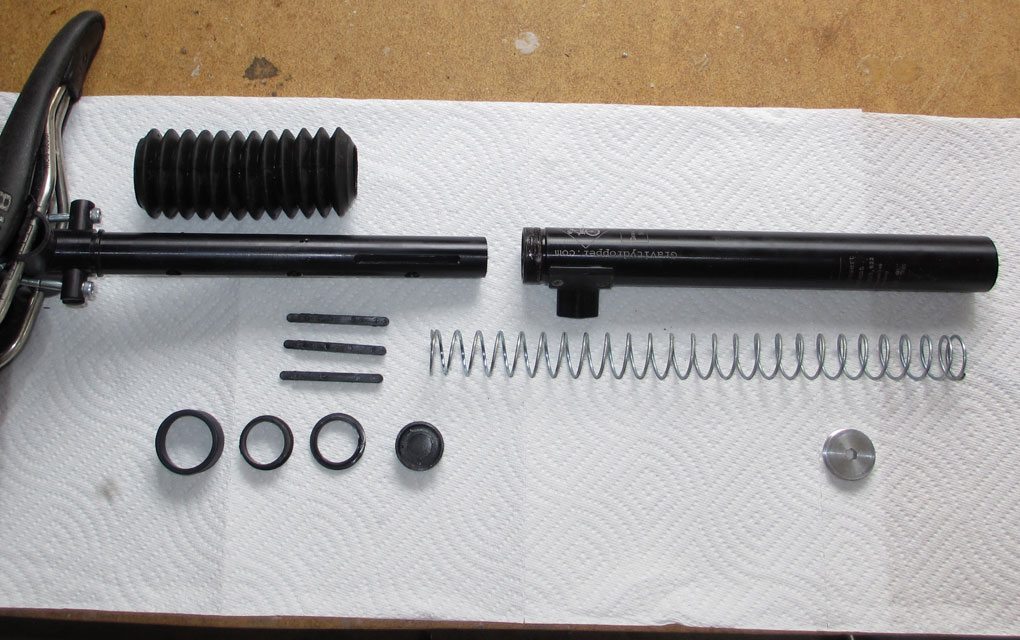

The Turbo utilizes an exceedingly straightforward design: an inner post with holes in it telescopes in an outer post. A cable-actuated pin engages into the holes, giving the post three different height options: all the way up, all the way down, and somewhere in the middle. A spring is used to return the seat to the “up” position.

The Turbo comes with plenty of options, including where the “middle” hole is located. I elected for two inches down on mine, though one inch down is also available. I also chose five inches of drop (as opposed to three or four), a left-hand remote (right is also available, but they’re not universal), a 30.9 diameter (several other sizes are available; GravityDropper will provide a shim, if necessary), and a standard two-rail saddle mount (also available for I-beam). You can even get custom engraving for an extra $15 in case you need your name on your seatpost.

While relatively light, the Turbo is still portly compared to a straight post. At 470 grams, it’s a bit lighter than a Rockshox Reverb (520 grams), and quite a bit lighter than a Kindshock IS-950r (605 grams) or a CrankBrothers Joplin (590 grams). Given its simplicity, however, I’m actually somewhat surprised the GravityDropper isn’t a bit lighter. It seems like the Turbo could potentially be redesigned to trim some fat, which could make the GravityDropper a great option for the weight-conscious crowd.

GravityDropper also offers the Classic model, which is similar to the Turbo but operates via magnets. The Classic requires that the rider “butt-tap” the seat to make it rise, but the Turbo requires no such tapping—you push the remote lever, and the seat comes up.

From my perspective, there are four main selling points of the Turbo: (1) the aforementioned simplicity; (2) the cable mounting position; (3) a proper two-bolt seatpost head; and (4) it’s made in the U.S.A., in my home state of Montana, no less.

The simplicity of the post became apparent after my first really muddy ride with it. The post got thoroughly gummed up and needed a rebuild. A good test of any mechanical piece of bike equipment’s simplicity is to take it apart and put it back together, and if I can successfully complete a rebuild without instructions, without breaking anything, and without ending up with spare pieces, bonus points are awarded. The Turbo definitely passed.

I rebuilt and cleaned the post in a relatively short period of time without any significant hiccups. There are only 11 parts in the post (a few more if you include the remote lever and actuation mechanism), and the complete rebuild required nothing more than a couple of hex wrenches and a pair of pliers.