Suspension 101: Basic Designs

We covered some basic concepts and definitions in our first Suspension 101 article, so you should now know the difference between a full suspension and a hardtail, and you should have a pretty good sense of the amount of travel you want in your bike.

Now we delve into suspension design, and how different companies try to achieve the “holy trinity”—how to make a suspension system that (1) absorbs bumps, (2) isn’t affected by braking, and (3) lets you pedal uphill without wanting to kill yourself?

In an ideal world, suspension would smoothly absorb all bumps, without being affected by drivetrain forces or braking. In reality, no such thing exists—all suspension designs are a trade-off of these three goals.

Over the years, there have been all kinds of interesting suspension concepts out there that try to achieve a good balance of the three ends. These days, however, there are a relatively small number of designs that make up the vast majority of the market.

Suspension Design – Forks

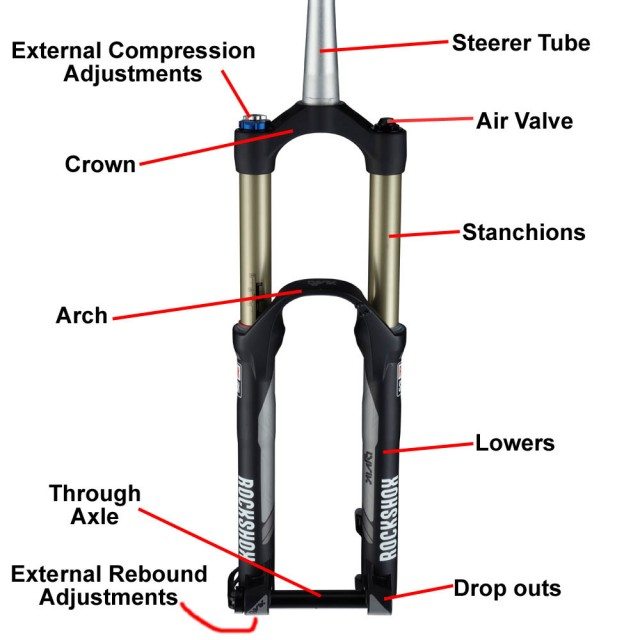

Most suspension forks have a fundamentally similar design these days. Essentially, they’re telescoping tubes with a spring inside.

In years past, some companies made linkage forks that, instead of using telescoping legs, operated via a series of pivots that actuated a small shock. (Google the Girvin Vector for one of the more common examples). Linkage forks, while offering a few benefits, have pretty much gone the way of the Dodo.

The vast majority of modern suspension forks are “upright,” meaning that a smaller diameter upper tube (the “stanchion”) slides into a larger diameter lower tube (the “lowers”).

There are a few companies making inverted forks, meaning that the stanchions slide up into a larger diameter upper tube (the Manitou Dorado is the most common example of this).

By using larger diameter tubing at the top, the inverted forks gain fore-aft stiffness. This also keeps the suspension movement smooth since the added stiffness helps prevent the telescoping tubes from flex-induced binding.

But the trade-off is that inverted forks tend to be much less stiff torsionally. This means that the front wheel will deflect much more easily because the fork has a more difficult time holding the wheel straight.

Arguments about which design is better fill hundreds of pages of internet chat rooms, but of the two major fork manufacturers (Rockshox and Fox), Rockshox makes only one inverted fork (the XC-oriented RS-1) and Fox makes only upright forks. So for now, at least, it seems that the upright fork advocates are winning.

Suspension Design – Frames / Rear Suspension

Like forks, most rear shock designs are fundamentally similar. But there are quite a few frame designs on the market today that use different configurations to actuate the rear shock.

At the most basic level, rear suspension involves one or more pivots that (1) allow the rear wheel to move up and down, and (2) push on a rear shock.

But the location of the pivots and the manner in which the frame pushes on the rear shock are the subject of plenty of debate.

There are basically three goals of rear suspension:

(1) The suspension needs to do a good job of absorbing bumps.

(2) The less that pedaling forces affect suspension, the better.

(3) Braking shouldn’t affect the suspension, either.

There are a few other considerations such as weight distribution, but in this broader discussion, those considerations are secondary to the three basic suspension goals.

In a perfect world, suspension movement would achieve all of those goals. In reality, no such technology exists. But there are several frame designs that aim to strike this balance.

An in-depth explanation of each concept would get quite long, but here’s a quick rundown of what’s out there and the pros and cons of each. Keep in mind that this is a very generalized discussion, and there are quite a few variations on each of these different designs.

High Single Pivot (example, Santa Cruz Heckler). A single pivot that is usually a few inches above the bottom bracket (often lined up with the outer edge of the largest chainring).

Pros: It does a good job of absorbing large bumps; no patents on the design (and therefore less expensive to build).

Cons: The suspension gives noticeable feedback in the pedals; not great under braking.

Linkage Driven Single Pivot (example: Kona Satori). The rear axle is on the chainstay, meaning that, as the suspension compresses, the rear wheel travels in a circular arc around a pivot location that’s usually just behind the bottom bracket. The shock is compressed via a series of links and pivots.

Pros: Decent bump compliance; no patents on the design (and therefore less expensive to build).

Cons: Not an efficient pedaler; some braking feedback.

FSR link (example: Specialized Enduro). Rear axle is on the seatstay, with a pivot slightly in front of and below the axle. Similar to the linkage driven single pivot, the FSR link has a modified axle path that leads to slightly better bump compliance and better braking abilities.

Pros: Good bump compliance; good under braking.

Cons: Not a very efficient pedaler.

DW Link (example: Pivot Firebird). A rear triangle, without pivots, is connected to the front triangle by two links that move in the same direction, one in the vicinity of the bottom bracket, one higher up on the seat tube, essentially making a parallelogram.

Pros: Pedals well; does well under braking.

Cons: Bump compliance isn’t quite as good as some other designs; patented design means it’s more expensive to build.

VPP (example: Santa Cruz Nomad). Similar to the DW link, except that the two links connecting the front and rear triangles move in opposite directions (i.e. one swings backward while the other swings forward).

Pros: pedals well; does well under braking.

Cons: Similar to DW link, sacrifices some bump compliance; patented design means it’s more expensive to build.

Other Dual Link Designs (example: Giant Reign). There are a few other companies that are building “dual link” designs that are similar to the DW link and VPP bikes. The pros and cons of these designs are potentially similar to the DW link and VPP bikes, but it really comes down to exactly how the linkages are designed on each specific bike.

ABP / Split Pivot (example: Trek Fuel). Trek puts its “ABP” design on most of its full suspension bikes. Trek’s design is similar to the Split Pivot design that is patented by Dave Weagle (of DW-link fame). Both designs incorporate a pivot that is concentric to the rear axle.

Pros: It has the good bump compliance of the linkage driven single pivot, but it does much better under braking.

Cons: Still not a particularly efficient pedaler; patented design costs a bit more.

If you’re all clear on the different approaches to suspension design and are interested in fine-tuning your ride, read on to the next article in our suspension series: Suspension 201: Anatomy of a Suspension System.

What about Knolly? It doesn’t appear to fit any of these categories? Similar to DW, but different enough that I’d think it MUST act a bit differently?

Also, looks like Yeti SB66 is similar to VPP?

Hey Brian,

The Knolly bikes use their “4xFour” linkage. In terms of the path that the wheel follows as the suspension compresses, that linkage is generally similar to Specialized’s FSR link (meaning they have a pivot slightly in front of and below the drop out). Knolly obviously uses some additional linkage to actuate the shock, which (as far as I can tell) is how they avoid infringing on the FSR patent. This will give the Knolly a different rate curve than other FSR bikes.

The Yeti “switch link” suspension design (used on the SB-66) is somewhat unique. It bears some similarities to a high single pivot bike; the rear wheel basically travels in an arc around the main pivot location above the bottom bracket. It also has a link that connects into the shock, but that link doesn’t directly impact the path that the wheel travels – it’s there to give the desired leverage ratio on the shock and to stiffen up the frame. But obviously that’s not the whole story; the eccentric bearings on the Yeti allow the chainstay length to effectively lengthen and shorten as the suspension compresses, which has an effect both on the pedaling efficiency as well as the leverage ratio acting on the shock.

On both the Knolly and the Yeti, you can essentially look at the suspension linkage as two parts: there are links that control the path of the wheel as the suspension compresses, and there are parts that compress the shock. For example, on the Knolly Chilcotin, the “extra” linkage on the upper part of the seat tube has no effect on the wheelpath – you could remove it and the wheel would still swing in the same arc. That linkage does, however, serve an important role in actuating the shock – the shape and location of those links will determine what the leverage ratio on the shock is at any given point in the shock’s travel.

Hopefully that answers some of your questions, but feel free to post any follow ups you might have.

-Noah

Knolly is simple 4-bar with Horst link. however it has additional ‘push-bars’, but it doesn’t change kinematics.

How about the KS link on a Banshee? Is that a VPP?

Hay Alex,

The Banshee KS link bears a little more similarity to a DW link in terms of pivot layout, but they’re not necessarily going to ride the same due to the differences in leverage ratios that each design produces on the shock. At their heart, both the DW Link and KS link are more or less parallelograms that move the rear wheel slightly rearward at the beginning of its travel, and then more upward further into the stroke. The KS link drives the shock directly with the rear triangle, whereas the DW link bikes generally drive the shock with the upper linkage arm. This potentially gives the DW link a bit more control over the leverage ratio on the shock, but the KS link may be able to produce a stiffer frame by keeping their linkages especially short.

“he KS link drives the shock directly with the rear triangle, whereas the DW link bikes generally drive the shock with the upper linkage arm. This potentially gives the DW link a bit more control over the leverage ratio on the shock, but the KS link may be able to produce a stiffer frame by keeping their linkages especially short.”

generally not true :) Pivot Mach 5.7 drives shock directly with rear triangle.

It all depends on designer and producer imagination :) and what they want to achieve – ratios, path, braking action etc.

How about Mongoose’s freedrive and GT’s new I-drive (basically the same as the freedrive) I’ve always wabted to try those and comoare them to my La pierre’s FSR.

The GT and Mongoose systems are somewhat unique, although they bear some vague similarities to other designs that have existed in the past. It should also be noted that the newer GT’s use a couple different designs (the Fury has a different pivot layout than the Force and Sensor). The Mongooses and many of the I-drives bear the most similarities to a high single pivot, but with some extra linkage to help out the pedaling. They basically have the upsides of a high single pivot (good wheel path for bump absorption), but with some of the downsides fixed (less chain growth).

In terms of efficiency, I’ve found these designs to pedal very well. As for ride quality, the couple of GT’s and Mongooses that I’ve ridden have felt a bit less supple than some other designs out there, but that should be taken with a large grain of salt. I’ve only ridden a small handful of these bikes over the years, so any blanket statements I make about how the suspension platform performs is really just a first impression.

I found the information here very helpful so Thank you sir.

What can you say about the suspension designs in relation to the different mountain biking disciplines out there? Like which is good for what and so on?

I really like the kona magic link bikes. they are essentially a four bar right? Also, thoughts on the mountain cycle battery frame? I think the design is unique too.

Hey Joshua,

You can talk to ten different engineers and get ten different answers about which designs are best for the various disciplines of the sport. Look at any of the top end XC bikes out there and you’ll see most of the designs represented. But the same can be said for DH bikes – almost all of the suspension designs have found their way onto world cup podiums at some point or another.

Ultimately, I think most of the designs can be effectively used in a bike for any of the various disciplines, but they might favor different riders. So a VPP bike that pedals well might favor a DH racer who emphasizes fitness, whereas a a single pivot design might be a good fit for a racer on a budget or someone who is more inclined towards pumping and “flowing” through the course rather than peddling their asses off.

Also keep in mind that each design can be tweaked to fit the needs of whatever discipline it’s being designed for. So a short travel DW link bike that’s intended for XC racing is going to look and feel quite a bit different than a long travel DW link bike that’s designed for DH. For example, compare the Turner Czar with the Turner DHR; both are DW link bikes at their heart, but there’s obvious differences.

The Kona magic link bikes were an interesting experiment that, in my humble opinion, are best treated as a brief lapse in judgment from Kona’s engineering department. The general premise was good; a bike that will act like a short travel xc bike on small hits, but was also able to swallow large hits when needed. The reality was that the rear end tended to be somewhat unpredictable in its reactions to bumps, not to mention heavy, complex, and expensive. There’s a reason Kona doesn’t make these anymore.

The Mountain Cycle Battery is a high single pivot – Mountain Cycle has been using that basic design since the early 90’s. The Battery is somewhat unique in that it’s a slopestyle bike with really short geometry, but as far as the suspension design goes, it’s pretty straight forward.

Thank you for the reply Noah.

Let us not forget that rear shock technology has gotten better through the years to the point that almost any suspension design has offers a solid ride due to the quality of the rear shock. I am currently using the latest Epicon RC rear shocks available from suntour and no dont shrugg just yet, hehe It actually offer fantastic small bump compliance for the money paid and considering that it offered compression adjust is another plus. Older models did not. Still not the best in square edged obstacles. I climb and descend on a four bar with an average rear shock, it an be very difficult. So-so traction, bump compliance,braking performance, not to mention loss of energy due to suspension movement when pedalling. But with the latest from suntour, I hardly even set the lockout when climbing steep singletrack, rocks, and roots since it smooth and works very well. Paid $100 for it.

I am no means advertising suntour, I am just saying that even a four bar suspension can ride better with the right shock installed. :)

Someday, I can get my hands on an Ibis mojo, my dream bike and I would be very happy but sometimes, I keep asking myself, Is it really worth it? They cost too much because of the patent right and of the part that it is made of carbon too. A high quality shock from fox or rockshox can improve my ride for less. then again, sometimes its not the shock but the technology and geometry the frame is built around that matters.

As for the mountain cycle battery, I was actually referring to the zen 2, I thought it was the battery bike.

And about Kona’s Magic Link. I agree that it was unique yet short lived. I liked the Idea since I wanted an purpose bike that can do it all. ride like an XC bike but descend like a DH bike. There simply no such thing as that. You can never build a good bike without compromises no matter how expensive it gets.

Definitely agree that suspension has gotten way better over the years – with a modern shock, the most inefficient bikes still pedal pretty well.

And yeah – the new Suntour stuff looks to offer a lot of bang for the buck. I briefly road their Auron fork and, while it wasn’t quite as good as some of the higher priced offerings, it definitely held its own.

Is a Mojo worth it? That’s a tougher question – it’s an awesome bike without a doubt, but once you get into higher end bikes, the performance differences gets increasingly narrow. The performance jump from a $500 bike to a $2000 bike is huge. But the performance jump from a $2000 bike to a $3500 bike is less significant, and generally speaking, the higher the price tag goes the less significant the performance increases become. Whether it’s worth it really comes down to your individual situation and preferences.

As for the Zen, that one isn’t entirely unique but its different from the Battery. It’s still a high single pivot at heart and it’ll retain many of the characteristics of a high single pivot, but it’s got a bit of linkage that actuates the shock that provides a changing ratio as the suspension compresses. This is a similar idea to something like the Santa Cruz APP bikes (the now discontinued Butcher and Nickel).

@Noah

Thanks again for the replies! im starting to dig your website. Hope to see more content, reviews and maybe enduro or trail tips in the future! :)

What about Ellsworth’s suspension? How does it work? Is it any good?

Hey Daniel,

People’s opinions on Ellsworths seem to be more polarized than any other brand I can think of; people either love them or detest them. Personally, I haven’t spent a whole lot of time on Ellsworths, so I can’t really comment based on my experiences. The basic pivot layout is similar to a horst / fsr link; there’s a pivot on the chainstay just in front of and below the rear axle, and there’s a rocker arm that actuates the shock. That said, I would venture a guess that an Ellsworth will ride quite differently from a comparable FSR bike because, even though the basic design is similar, the exact locations of the pivots are quite different.

Ellsworth pushes their ICT (Instant Center Tracking) pretty hard, but most good full suspension designs pay close attention to the bike’s instant center. Santa Cruz has a pretty good explanation of instant centers here: http://www.santacruzbicycles.com/en/us/news/346.

Since I haven’t ridden an Ellsworth, I can’t really say if their design offers any substantial improvement over an FSR link, or any other design for that matter. It does seem like Ellsworth frames have struggled with some warranty issues over the years, but those issues may be behind them at this point. If you’re considering an Ellsworth, it’s also worth paying attention to their geometry; thus far, it doesn’t look like they’re jumping on the “longer is better” bandwagon.

Thank you Noah for the reply. Much appreciated.

Pardon my ignorance but why is Ellsworth the most polarizing bike if their suspension design is not that extra ordinary or revolutionary? And you said that they are not the only design that pays attention to ICT, then why the love it or hate it status? Is there something unique to their suspension design that will make one either love it or hate it (more than any other bike) ? Does their slightly different pivot locations make their Horst Link better or worse?

Well, that’s a good question that I’m not sure I have the answer to, but since this is the internet, I’ll do some speculating: From what I’ve read, there are quite a few people that really like how the Ellsworth design rides and they tend to defend the bikes. On the other hand, there are also quite a few people that 1) found the frames to be prone to breaking, 2) found the frames to be flexy, 3) found that Ellsworth’s customer service was less than spectacular, and/or 4) found that Ellsworth’s somewhat over the top marketing spiel and blatant bashing of other designs to be lacking tact. For some reason, these two camps seem to like to argue a lot.

Ellsworth had some patents on their design (which I believe are expired at this point), so in that respect, the design is unique. As for whether the design is better or worse, I guess I can’t really say since I haven’t spent much time on one. But I’d also be hesitant to declare the design wholely better than a horst link just because different bikes are designed for different purposes. For example, just from looking at the Ellsworth bikes, you can see that the design becomes somewhat problematic when used in longer travel applications – the rocker arm becomes extremely long, which means it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the rear end of the bike stiff without taking on a big weight penalty.

So, long story short, suspension design and the location of the pivots certainly matters, and my impression (having not really ridden an Ellsworth) is that their design works very well in some applications. But as with most things, there are other factors at play.

Thank you again Noah for indulging me.

I am looking at getting an enduro bike and really want to understand suspension designs from a factual/physics point of view instead of relying on what marketing materials claim. Thus all my questions.

As to why I was specifically asking about Ellsworth… well from your article, not much was discussed about their (specific) suspension design and I have ridden a couple of Ellsworths and want to understand their suspension design logic. But I am not only interested in their design logic. In fact, I am also interested in all other manufacturer’s designs. I just wanted to start learning from the most simple designs before moving on to more complex ones.

I know that the best way for me to decide which bike to get for enduro purposes will be to try them all. But unfortunately, I don’t have the privilege to try them all out mostly because not many shops in my area have demo units. So I will have to rely on my understanding of the suspension designs and “virtually ride” the bikes in my head based on my understanding of the designs. (Ellsworth dealer here has demo bikes…but don’t want to purchase based on that alone without considering other designs).

Is there a site or article that you can refer me to for me to read up and understand more about mtb suspension designs? I want to understand more so I can decide which bike to get.

Thanks in advance Noah. I have learned a lot from your site. Keep it up!

I hear you; there’s so many designs out there that look interesting, but it’s hard to find a way to swing a leg over more than a small fraction of the options. But when it really comes down to it, it’s really hard to look at a bike on paper and know what it’s going to ride like. There’s so many variables, and some really minor changes can make a big difference. For example, look at the rearward pivot location (the one near the axle) on an Ellsworth Epiphany vs a Specialized Enduro vs. a Norco Range vs. a Rocky Mountain Altitude. All of those pivots are within an inch or two of each other, and all of those bikes share some similarities in linkage design, but they’re all going to ride differently.

That’s not even getting into shock tunes, leverage ratios, frame stiffness, wear on the bearings, wear on the shock / DU bushings, and any number of other factors that frame designers (hopefully) are taking into consideration. And that’s also ignoring the fact that modern shocks are getting to be pretty damn good, and they can help minimize some of the downsides that otherwise sub-par frames might exhibit.

But to get at your question, I think the “Joe’s Corner” blog on the Santa Cruz site has some good information: http://www.santacruzbicycles.com/en/us/joes-corner

Also, here’s a site that has graphs of various suspension traits for a ton of bikes, and if you can read spanish (or want to deal with google translate), there’s some discussion: http://linkagedesign.blogspot.com/

But like I said, it’s tough to get a really good idea of how a bike will ride just by looking at numbers and graphs on paper. If you can make it happen, something like outerbike (http://www.outerbike.com/) is a great option to try a lot of different bikes. You can ride them, make some notes, and then go back and look at the graphs and compare designs. At least for me, that makes it a lot easier to start wrapping your head around how certain suspension designs actually compare, and then you can use that information to assess other bikes that you haven’t ridden yet.

Personally, I find that the bikes I like best aren’t always the “best” suspension design. Geometry, weight, and componentry, and a few other factors all play as big (if not bigger) a factor as the location of the pivots.

Hello again Noah!

Pardon my lengthy messages. I guess what I really want to know is this:

I realize that all suspension designs want the same things… as per your article “how to make a suspension system that (1) absorbs bumps, (2) isn’t affected by braking, and (3) lets you pedal uphill without wanting to kill yourself?”

I also realize that there is more than 1 way to achieve the above. But is there one method that is superior to all in achieving the objectives? And if there is one “holy grail” method, which is it? And are different suspension designs just a way of achieving the objectives just a way of getting around patents of superior performance or are they really necessary innovations? Is simpler designs better or are complex designs needed as simple does not work?

Sorry for my complex questions. Just so many designs and theories that I am getting dizzy.

Hey Daniel,

I guess the short answer is: no. There isn’t any design (at least none that I’ve found) that does a perfect job at absorbing bumps of all shapes and sizes while still remaining fully active under braking and that isn’t affected by pedaling forces in any gear. I’m no engineer, but I would say that such a thing is pretty much impossible, at least with bikes configured as they are now. I would also add that, while those three attributes are what a suspension designer is considering on a fundamental level, don’t forget that there are quite a few other factors at play (cost, patent issues, weight, stiffness to name a few).

One reason it’s impossible is that bike drivetrains have gears, which means that the forces exerted on the suspension by the chain come in at varying angles, depending on what gear you’re in. As far as I can tell, it’s not possible to make a suspension that isolates those forces in all gears. This is one reason that a few companies continue to play with gear boxes on bikes, but those options have yet to really catch on (they’re expensive, somewhat unreliable, and they tend to be heavy).

So since it’s more or less impossible to achieve that holy grail, companies will prioritize different traits. Some bikes will absorb bumps better, some will brake better, and some will pedal better. Finding the right balance of those three traits for a given bike is what frame designers are trying to do, but different people riding in different locations will have their own priorities.

Maybe all of your riding involves mellow fire road climbs where pedaling efficiency doesn’t really matter because you can just throw your rear shock in “climb” mode. Or maybe all of your descending is super steep and riddled with brake bumps so a suspension design that stays active under braking is important. Or maybe you ride a broad range of trails, so you need the best balance you can find.

These days, I would say the bikes that come the closest to achieving the holy grail are the ones that are working closely with the suspension manufacturers and building their frames with a thorough understanding of the damping circuits in the suspension. Like I mentioned before, a good shock can make a mediocre design feel pretty good. Similarly a good rear shock can make a great design feel fantastic (and a bad shock can make it feel horrible). Take a look at Tom Collier’s review of the Avalanche Chubie rear shock on his Santa Cruz Nomad; the shock substantially transformed how that bike rode, and obviously didn’t involve any changing of the frame design. http://blistergearreview.com/gear-reviews/avalanche-chubie-rear-shock

I guess the take away point is really that there are a ton of variables at play when it comes to talking about rear suspension. An in depth discussion of any one aspect could literally fill an entire book (look to the motorcycle world if you want to find good reading on suspension design and theory). There is no holy grail; it’s all a matter of trade offs. What trade offs makes the most sense for you really depends on what you’re looking for and what type of trails you ride most frequently.

Noah… Thank you again for your reply. Very enlightening.

I guess I will really have to actually try as many different bikes with different suspension designs on the trails that I actually ride… cannot be be done “virtually in my head”. I was hoping to shorten the decision process by choosing 2 or 3 different suspension designs/brands based on sound physics principles and going by ride feel after narrowing down my choices.

Maybe I should just get a hardtail and let my legs do all the work. Hahahahahaha! (legs are best suspension right?!)

Best regards,

Daniel

Heh. Legs are indeed very good suspension, but they don’t work quite so well on some of the smaller bumps. I do still spend a lot of time on my hardtail though!

But yeah, there’s no substitute for riding lots of bikes. And I wouldn’t over think it too much; there are lots of really good bikes out there, and all things considered, the differences between them are relatively minor.

Hell, riding my Canfield Yelli Screamy (hardtail 29er) back to back with my Specialized Enduro (6.5″ travel 26er) on the same enduro course, I’m not all that much faster on the Specialized – and those are completely different bikes. When you’re comparing two bikes with similar geometry, wheel sizes, and travel, the real world differences at race pace are probably going to be measured in fractions of a second. That’s not to say it doesn’t matter, it’s more to say that you’ll be fastest and have the most fun on the bike you like best, which isn’t necessarily the bike that has the “perfect” design.

Noah!

“But yeah, there’s no substitute for riding lots of bikes. And I wouldn’t over think it too much; there are lots of really good bikes out there, and all things considered, the differences between them are relatively minor.”

” it’s more to say that you’ll be fastest and have the most fun on the bike you like best, which isn’t necessarily the bike that has the “perfect” design.”

– Well said.

Am now looking into the article about how good/great shocks can transform a bike… to confuse me some more! Hahahaha!

Thanks again Noah!

quick one..

Noah!

debating on: Santa Cruz Nomad C, Pivot Mach 6 Carbon or Intense Tracer 275 C???? opinions ;)

Ha! That’s a quick one???

Well, to start with, the Nomad and the Tracer are both VPP designs, so they at least share some basic similarities. The Mach 6 is a DW link, so to some extent it’s the odd one out.

I haven’t spent a ton of time on any of those bikes, but of the three, I’ve spent the least time on the Nomad. So, that being said, here are the broad generalizations that I’d say about those bikes (and, these being broad generalizations, I’m sure there are plenty of people who might disagree).

The upside is that all three of those bikes pedal pretty well. If I was going to spend all day pedaling uphill on a ~6″ travel bike, these three bikes would be high on my list of contenders. There are, of course, trade offs.

In my experience, the trade off on the Mach 6 is small bump sensitivity. It has a reasonably firm pedaling platform at the cost of sucking up those smaller bumps along the trail. But it has good mid-stroke support and it doesn’t get crushed on bigger hits.

On the Nomad and the Tracer, I think the trade off is mid-stroke support. On many of the VPP bikes I’ve ridden, there’s a fairly distinct platform where the suspension seems to stiffen up. This really helps the bikes pedal well, but the transition past that platform often feels a weird to me. Particularly when I’m trying to pump the suspension or pop the bike off of a small lip, I feel like the platform drops out from under me. This isn’t a problem for straight up plowing, but it makes the bike feel a bit less lively. I noticed this feeling in my brief time on the Tracer, and I’ve noticed it on the older Nomad. I’ve only had a very brief parking lot test of the new Nomad, which isn’t really enough to draw any conclusions, but that feeling seemed less noticeable in the couple of minutes I was aboard the bike, at least compared to the Tracer.

All that said, the suspension tune on all three of these bikes is particularly critical, and a good tune can minimize the downsides (and maximize the upsides).

So, long story short, they’re all really nice bikes. If you haven’t ridden any of them and/or don’t have any clear preferences as to DW vs VPP bikes, I’d probably suggest making your decision based on other factors (in rough order: 1) fit; 2) parts spec; 3) price; 4) weight).

Thanks a lot Noah!

I demoed the Nomad for a couple hrs at Grand Targhee resort, I did an uphill lap and it did good (1X10shimano) then I went for the lift service to ride their DH trails and it felt good but like you said…”the suspension tune is particularly critical” and a couple hrs were not enough to get the real feel.

I own 2 bikes a Trek ’08 remedy 8 with 2014 suspension (pike & monarch plus) and components (xx1DT, guideRSC,150mmLevTi) sweet set up and a DH Ventana El Cuervo (a tank), I’ve been riding these bikes for 6 years (slc-PC,UT), now I’ve got my eye on the Nomad with CC DB air CS or Custom Santa Cruz Nomad Rear Shock by BikeCo.com

Thanks

I used to own a locally produced FS bike before that had the four bar configuration. It was a light bike but flexy, yet I’ve used it till i got another one. My replacement is not exactly new either but the suspension design is remarkably different. From a four bar, i went to a floating single pivot, in particular the Cannondale Moto’s hatchet drive. The Cannondale Moto kept afloat using a fox shock while the four bar bike kept afloat with an epicon shock (which worked remarkably well by the way despite the namesake).

All i can say is that, both bikes handled suspension wise remarkably well. Both mitigated the bumps really well and traction is superb. I did have to rely on pedal platforms, like the pro pedal in the RP fox shock and lowering the compression setting on the epicon shock to make difficult climbs work great.

But the ride was never perfect. Its not the suspension design that mattered though, it was the fit. The local four bar bike with the Epicon had a ridiculous top tube, the chainstay is longer than most and the wheelbase is longer too. lastly, it was an XC/trail oriented bike so geometry is different.

The cannondale moto carbon however, it was a small and I fit a shorter stem, a wider bar so cockpit wise, I was comfortable. Also the wheelbase is short and the chainstay is also shorter, lastly the bike is stiff because of the carbon mainframe and beefy rear triangle. The bike is an AM bike by the way.

I know its like comparing apples to oranges but the bottomline is, there’s no suspension design that works best for each facet of mountain biking.

Each suspension design is great, but, fit, comfort, the stiffness of the bike at least for me matters the most in the end. Plus, the advent of state of the art shocks today, even single pivots, the most basic in suspension design for bikes can ride amazingly well and especially when the geometry is spot on among other things.

To demo bikes is the best way to know which one rides the best. But the best will always a subjective criteria. At the moment, I love the floating shock design. Going through rock gardens feels king, and climbing is remarkably comfortable as well even with the shock fully open. I long to try a trek ABP, full floater though or maybe commencal’s older FS design and see if there’s a remakably difference. provided of course the bike geo among other things are spot on.

hi, how about the Felt equialink design?

Hey Eyal,

The Felts are an interesting bunch; lots of links and pivots. I owned a Felt Redemption for a while, which is a bit longer travel than most of the Felts on the market today.

While most full suspension bikes these days are some variation of a 4-bar design, the Felts are actually a 6-bar design. Whether that’s a good thing or not probably depends on who you talk to. My take is that 1) the design seems to pedal reasonably well while still being pretty active over small bumps, 2) All those pivots make it a bit of challenge to keep the frame weight down, and 3) all those pivots and links also make it a bit more challenging to keep the rear end stiff.

I can also say that my Redemption tended to blow through its travel and bottom out harshly, but if I were to guess, I’d place a lot of the blame for that on the rear shock tune (a DHX Air, which was somewhat notorious for that problem).

Thanks for the excellent article and Q&A.

I am curious how you would classify the Canfield Brother’s Balance suspension design? Because of my ignorance, I don’t even want to guess but it is definitely touted as being an excellent design and great riding bike (I’ve put approx 1000k on a yelli screamy so I enjoy their take on things—-even though I’ve now moved on from the yelli)……

Hey T.C.

I haven’t spent much time on the Canfield full suspension bikes, so I can’t really comment on how they ride. All of the current full suspension Canfields use some variation of a 2 link design, which is generally similar to a DW link or Giant Maestro. That said, the devil is in the details, and it’s a reasonably safe assumption that the Canfields probably ride a bit different than, for example, a DW-Link equipped Pivot.

At least on their DH bikes, Canfield has emphasized the rearward movement of the axle path. The main idea there is to more efficiently get the rear wheel out of the way of bumps, and by all accounts, the Jedi does that really well. It does, however, present a couple of challenges, the first being that a rearward axle path means that the chainstays effectively get a lot longer as the suspension compresses. This can make for some odd and undesirable pedaling characteristics, which Canfield addresses on the Jedi by using an idler pulley. From talking to people that have spent some time on a Jedi, it also sounds like the rearward axle path takes a bit of getting used to in hard corners – as the bike compresses into the corner, the rear end gets significantly longer, which might feel weird to someone coming off of a bike that keeps the rear end relatively short throughout its travel.

Just from looking at the Balance and speculating about its suspension movement, I’d guess that it doesn’t have nearly as much rearward movement in the rear end as the Jedi. On the upside, this makes dealing with pedaling forces a lot easier. On the other hand, it’s probably not quite as much of a bump swallowing monster as the Jedi.

Thanks for all your insight Noah.

The Jedi is a very unique bike in all the ways you mentioned, especially radical rearward wheel path. The Balance and Riot use a different design, Canfield Balance Formula, patent #US 9,061,729 B2. Issued this year and shows how to achieve the “Holy Grail” of pedaling efficiency.

With all the suspension designs and media hype,you really need to demo different designs on trails you like to ride. Then you can see what feels good for you, it’s very subjective. It would be interesting if you could ride3-4 bikes with the suspension somehow covered, like a blindfold test,then choose one and see if it’s the design you thought it was.

What are your thoughts on the new 2015 updated switch infinity suspension on the Yeti SB6 C?

So, I haven’t seen any posts for the DiamondBack knucklebox migration suspension? I am looking at the Mission 2 but not sure if this old technology, or if its worth the discounted price?

Hey Mike,

At its heart, the Diamondback knucklebox design is a linkage driven single pivot (like the Kona pictured in the article). The rocker arm is in a different place than on the Konas, and I would assume that the suspension action might feel a bit different, but in terms of the basic upsides and downsides of the design, it definitely still falls into that linkage driven single pivot category. Incidentally, the older Diamondbacks that had a more triangular linkage piece and a vertical shock orientation also fall into that same category.

-Noah

i have an old single pivot trek bruiser 3, and i cant seem to find a suitable rear shock for it..can you give me some advice on what kind of rear shock should i put in it?..most rear shock that i put doesn’t seem to work,even if it has a 600lbs/in of coil in it.

thanks

SO what is the best type of suspension

What could you say about the round tube turner DHR’s I know that they’re a single pivot, but they’re not a true single pivot, I think they called it a “modified single pivot”.

Hey Tyler,

I’m assuming you mean the older DHR (the newer ones are a DW link). All of the older DHR’s were linkage driven single pivots. So the rear end pivots in a circle around a single pivot that’s just above the bottom bracket (the same basic pivot location as the Kona Satori in the article). To actuate the shock, there’s a short swing link that both helps stiffen the rear end, and provides a means to modify the leverage on the shock as the suspension compresses. So, at it’s heart, it’s pretty similar to that linkage driven single pivot on the Kona Satori, but the configuration of the linkage is obviously quite different, and the DHR gets the job done with fewer links.

What do you think about Diamondback Knuclebox?

Noah, if you would be so kind as to describe the differences and maybe advantages of Canfield’s Balance suspension design and Canfield’s Formula suspension design (used on the Balance and Riot) it would be much appreciated! Just to throw out another brand that hasn’t come up yet, how does the YT Capra’s suspension design compare? Thanks

Hey Logan,

Like I mentioned above, all of the current Canfield bikes are generally based around a dual link design that’s vaguely similar to a DW link in terms of layout (2 links, both rotating in the same direction). But don’t take that to mean that they’ll necessarily ride like a DW link bike; there’s way more to it than that.

Like Lance mentioned in his comment, the Jedi’s linkage is designed to achieve a bunch of rearward travel – when the suspension compresses, the rear wheel moves backwards (as well as up). This can help the bike roll over square hits more efficiently, but makes things tricky when dealing with pedaling forces. The design on the Balance and Riot, while still a dual link setup, is designed with efficient pedaling in mind (and that’s what Canfield’s “Balance Formula” patent primarily deals with). So it has way less rearward travel than the Jedi, but it’ll pedal relatively efficiently.

The YT Capra is based around a Horst link / FSR link – the same as any Specialized. The main difference here is that the shocks on the Specialized bikes are generally driven off of the swing link, whereas the Capra’s shock is driven off of the seatstay (although it still has a swing link to stiffen things up and modify the leverage ratio a bit). The Jeffsy uses this same linkage layout, but the Tues drives the shock off of the swing link. That difference really just come down to what the company is trying to achieve with their leverage ratios for each bike.

Noah,

The longest running thread!! Thanks for all these amazing explanations. Very thorough.

How different or same is the Niner CVA suspension from these others. And I’ve heard that the BMC APS is just a DW link. Can you kindly shed some light on the pros and cons of these two? Thanks.

Hey Aaron,

Both the Niner CVA and the BMC APS are, at their heart, dual link bikes with co-rotating links (meaning they move parallel to each other). The exact link layouts are a little different though.

The Niner CVA bears some basic similarities in terms of link layout to the Giant Maestro design (the lower link on the Maestro is above the bottom bracket, while the CVA is below, and both designs are using links that are a bit longer than DW link bikes). While the exact traits are going to vary quite a bit from bike to bike, my experience has been that the Niners tend to pedal fairly efficiently, and have slightly better small bump sensitivity than some of the DW link bikes.

The BMC APS linkage definitely has a lot of similarity to DW link bikes – they’re both using relatively short links operating parallel to each other. The APS design also ends up with fairly similar pedaling characteristics and leverage ratios as some DW link bikes. Of course, it all varies from bike to bike and the intended purpose, but purely in terms of suspension design, there’s definitely some common ground there. I haven’t ridden any BMC’s, but based on the basic linkage layout and the numbers on the suspension kinematics, I’d expect them to ride somewhat similar to a DW link bike.

Thanks for this great thread, so much information!

Is there a consensus yet on the best climbing dual suspension setup?

Thanks again!

Just chiming in to say I learned more about suspension from this article and the comments by Noah than from several sites I have been to.

I am currently looking for my first full suspension, mid travel bike in the 3k range, and truly appreciated this page. I want to have a solid understanding of bikes before I buy, and this has helped clear up the muddy water where each manufacturer has the best suspension… according to them.

Thanks again!!

I’ve been looking to finally upgrade to a fs after about 20 years on a hard tail. I was looking at the Motobecane Hal6 from bikesdirect. Would that be a DW link suspension? Any thoughts or feedback would be appreciated. The reviews seem to be pretty good but I know a lot of technology goes into proper frame design. Thanks!!

Thanks for the good article to help me as a consumer be informed with my next purchase. I have a 2000 GT i-Drive and it has held up great all this time. I am thinking about a new bike so I went to all the bike shops around. I rode Scott spark 960, Trek fuel ex7, specialized camber lowest spec and a yeti sb 4.5. Granted I just rode around the sidewalks and played around on the curbs and stuff but all the bikes felt like they were bending in at the bb when I stood up and bounced my weight on them and also pedaling hard. That is except for the yeti. Is this a matter of those bikes being around 2K and the yeti at 5K or is it their design? I prefer the feel of my old bikes suspension over the 3 new bikes that were “cheaper” but the yeti was familiar feeling and had all the new stuff like modern geo, disc brakes, new tire size etc… was the iDrive ahead of its time or what? I could be just used to riding it all these years, but it felt better with the old spring shock and mechanical Judy c fork. It’s a short steep and heavy bike that needs to be replaced but not sure if I will like one of the budget options.

I think the patent on the FSR is now expired, so companies can produce FSR-type designs.

Hi

What kind of linkage would my 2013 sunn charger S2 be? Looks like an fsr link but the “link” is inside the front triangle instad of on the seattube. Thanks