Öhlins TTX1 and TTX2 Air

MSRP:

- TTX1 Air: $740

- TTX2 Air: $780

Adjustments: Air pressure; rebound; low- and high-speed compression

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- TTX1: 406 g (210 x 55, w/o mounting hardware)

- TTX2: 477 g (210 x 55, w/o mounting hardware)

Bolted To: Guerrilla Gravity Trail Pistol, Propain Hugene

Test Location: Western Washington

Reviewers:

- Zack Henderson: 6’, 160 lbs / 183 cm, 72.6 kg,

- David Golay: 6’, 175 lb / 183 cm, 79.1 kg

Test Duration: 7 months

Metric:

- 190 x 37.5 mm

- 190 x 40 mm

- 190 x 42.5 mm

- 190 x 45 mm

- 210 x 47.5 mm

- 210 x 50 mm

- 210 x 52.5 mm

- 210 x 55 mm

- 230 x 57.5 mm

- 230 x 60 mm

- 230 x 62.5 mm

- 230 x 65 mm

Metric Trunnion:

- 165 x 37.5 mm

- 165 x 40 mm

- 165 x 42.5 mm

- 165 x 45 mm

- 185 x 47.5 mm

- 185 x 50 mm

- 185 x 52.5 mm

- 185 x 55 mm

- 205 x 57.5 mm

- 205 x 60 mm

- 205 x 62.5 mm

- 205 x 65 mm

Intro

We came away quite impressed with Öhlins’ TTX22 coil shock when we reviewed it a few years ago, but what about their two air options, the TTX1 and TTX2? And how do the TTX1 and TTX2 compare to each other, given that — as we’ll detail more below — they share a damper design, but pair it with substantially different air spring layouts?

We were curious to find out. And now having had two different reviewers spend a lot of time on three different TTX Air shocks, we’re ready to weigh in.

Design

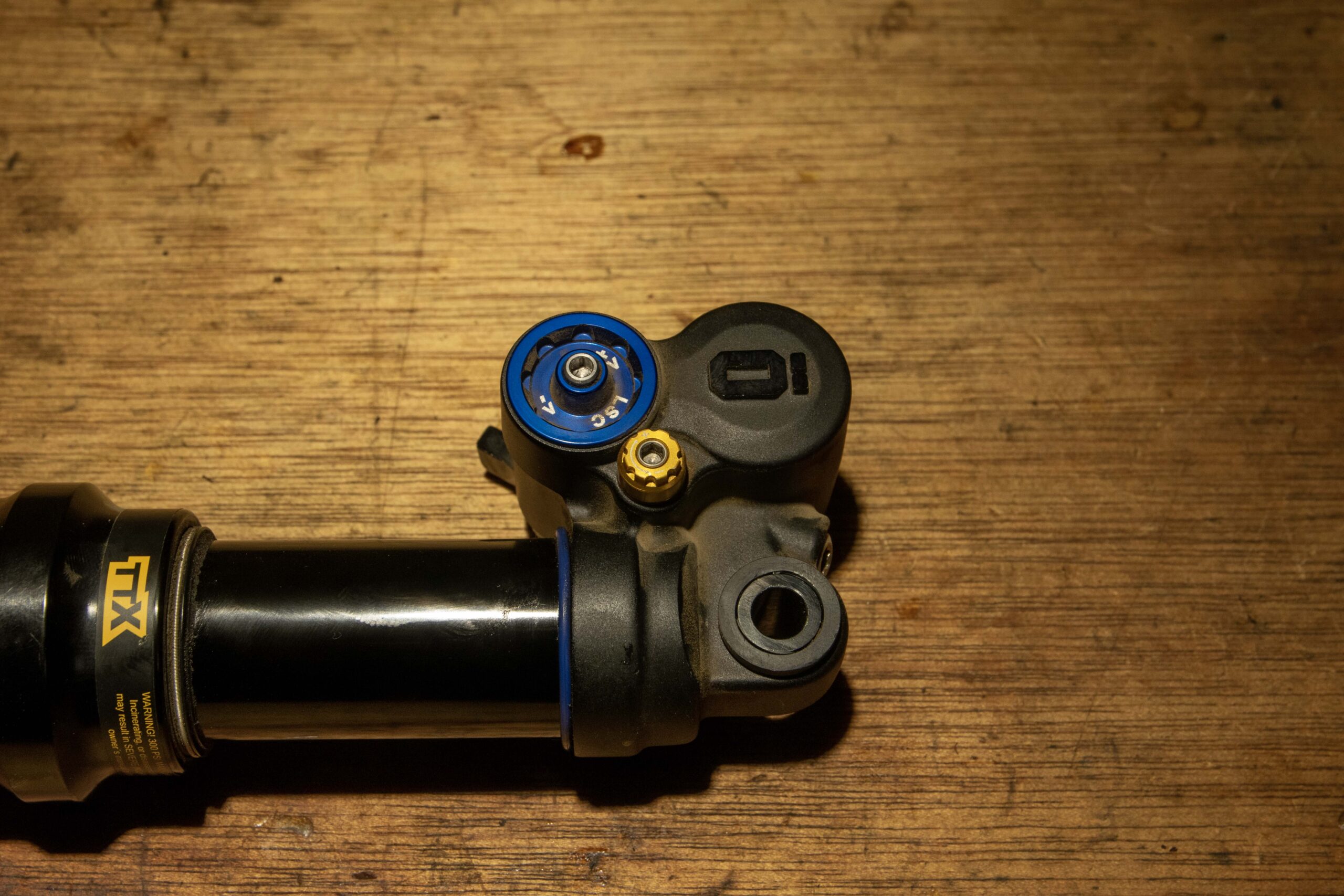

Both the TTX1 and TTX2 use a damper design that’s conceptually similar to that used in their TTX22 coil shock that I reviewed a couple of years back, just reconfigured and re-tuned for the packaging demands and performance characteristics of the air-sprung layout. As per usual for Öhlins, the damper is a modified twin-tube layout with a check valve that effectively makes it perform more like a monotube damper on rebound. If you want to get nerdy on the details of how that works, our TTX22 review has a rundown, but it’s not critical for getting a handle on the TTX1 / TTX2’s performance — as we’ve noted before, drawing particular conclusions on the performance of a given damper based solely on whether it’s a mono- or twin-tube layout doesn’t tend to mean much.

[The TTX1 and TTX2’s damper is packaged a bit differently from that of the TTX22, including moving the rebound adjuster from the lower eyelet to the shock body, but the concept is still similar.]

And speaking of adjustments, the TTX1 and TTX2 both get adjustable rebound plus high- and low-speed compression, with a climb switch. The climb switch is actually packaged into the same adjuster as the high-speed compression, owing to the unusual internal arrangement of that adjuster. In most cases, high-speed compression adjusters work by adding spring preload to a shim stack, changing the amount of force needed to get the shim stack to start to open and bypass the low-speed circuit; Öhlins instead uses a lever that varies the flow path that oil takes to reach the shim stack, opening and closing different apertures so that the pressurized oil hits different parts of the shim stack where it has differing amounts of leverage, effectively, over it. It’s a different way of achieving a similar idea to Fox’s VVC design in some of their newer forks and shocks, with the goal of making a more fundamental change to the damping curve, rather than creating a “blow-off” effect where it takes more force to open the shim stack in the first place due to added preload but isn’t changed as much at higher shaft speeds past that point where the high-speed circuit opens up.

The tradeoff to that arrangement is that the Öhlins shocks only have two different settings for the high-speed compression, plus a third that serves as the climb switch; there’s far more resolution on the low-speed compression and rebound adjusters, with 12 clicks available on each. One minor downside of moving the rebound adjuster to the shock bridge from the lower eyelet (as compared to the TTX22 coil) is that it’s no longer tool-free on the TTX1 and TTX2 (requiring a 3 mm Allen key), though it’s also potentially easier to reach on some frame designs.

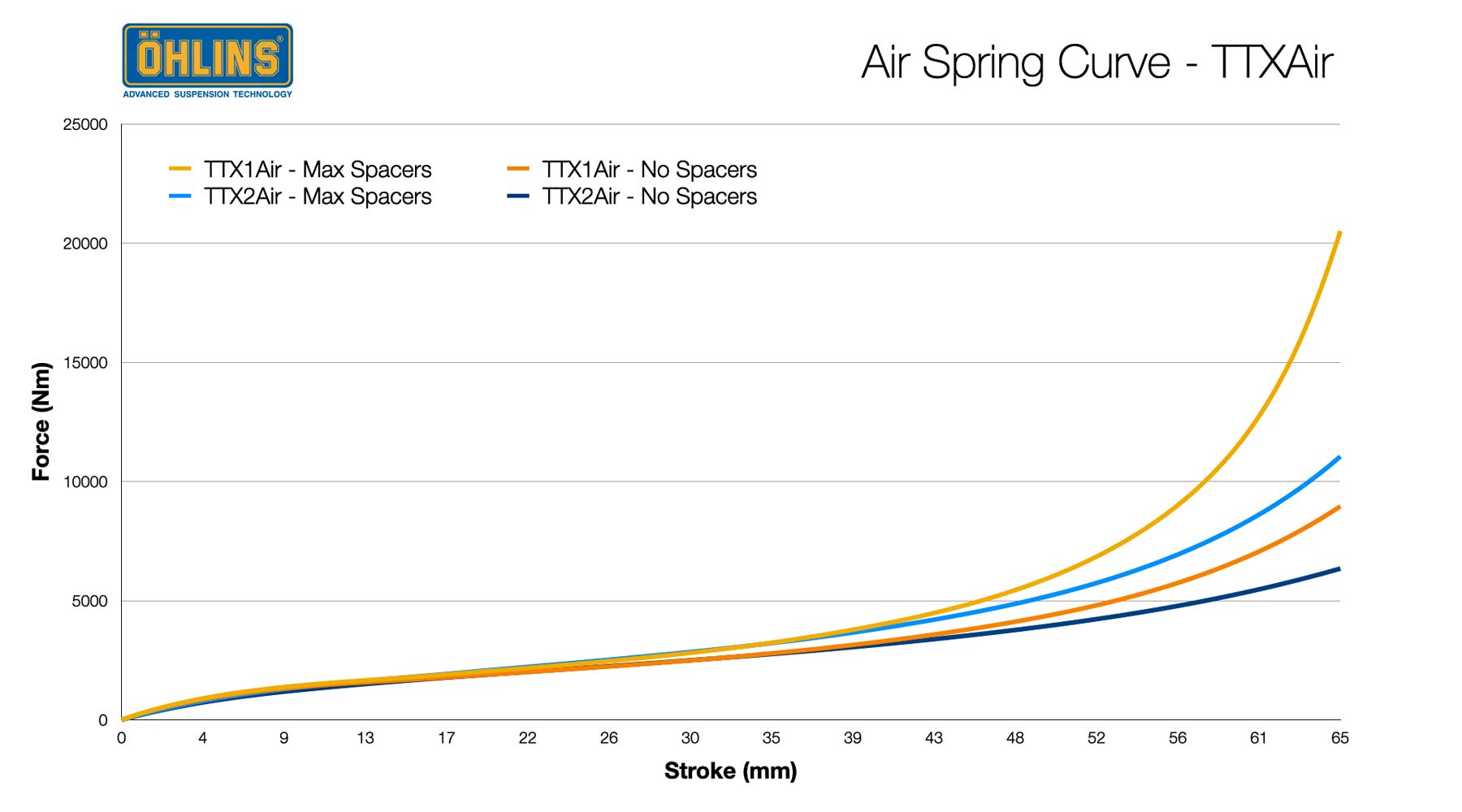

[The differences in end-of-stroke progression in that graph are dramatic but don’t overlook the fact that the TTX2’s force curves are also flatter early in the stroke.]

As indicated in that graph, both the TTX1 and TTX2 have options for various volume spacers to alter the overall amount of progressivity, similar to most other air shocks out there. For both the TTX1 and TTX2, installing the spacers requires deflating the shock, unthreading the air can, and snapping the desired spacers on or off as needed. In the case of the TTX1, removing the air can requires a strap wrench plus some way to hold the lower eyelet steady (bench vice, a box wrench, your frame, and many more options are potentially valid); in the case of the TTX2, there’s the additional option of a slotted Shimano bottom bracket tool (e.g., the Shimano TL-FC32) in lieu of the strap wrench.

The TTX2 also has the option for additional volume spacers in the outer sleeve to help offer all the different increments of total spacer volume. Öhlins’ guide to the various options is, frankly, pretty confusing, but the short version is that there are some medium-size spacers that clip onto the damper shaft that work on both shocks; the TTX1 uses different damper-shaft-mounted spacers for the smaller sizes, while the TTX2 uses thinner spacers in the outer sleeve for the finer increments. The chart that explains it in more detail can be found here; Öhlins’ support is there if you need more help.

It’s also relatively easy to change the stroke on the TTX1 and TTX2, though it does require a set of 8 mm shaft clamps in addition to the tools listed above. For that operation you need to open the air can as if to change volume spacers, but then also unthread the eyelet from the damper shaft (using the shaft clamps to hold the damper shaft steady, and with a little applied heat to break the thread locker). The travel-adjusting spacers — included with both shocks, in 2.5 mm increments — simply slide onto the damper shaft once the eyelet is removed. The damper shaft is solid and there’s no need to bleed the damper as part of that operation.

Interestingly, Öhlins isn’t offering the TTX2 (or the TTX1, less surprisingly) in longer 250 mm eyelet / 225 mm Trunnion mount versions for use on modern DH bikes — if you want an Öhlins shock in those sizes, you’re looking at the TTX22 coil.

As a final note on the design, it’s worth noting that both the TTX1 and TTX2 have somewhat unconventional layouts that can present compatibility issues. While the air valve is in different places on each shock, that valve is placed at the opposite end of the damper adjustments. On some bikes (like Zack’s Propain Hugene), this can present some clearance issues where the frame may have been designed for shocks with a more conventional architecture that keeps the air valve and damper adjustments on the same end of the shock, like the Fox Float X and RockShox Super Deluxe. While the TTX1 did work on the Propain, the clearances were such that it took some serious fiddling to get to the air valve.

On-Trail Performance

David: I’d planned on using a Guerrilla Gravity Trail Pistol as the test platform for the TTX Air shock, but that presented a bit of a dilemma: would the TTX1 or TTX2 be the better option? Öhlins recommends the TTX1 for shorter-travel and / or less progressive bikes while steering folks on longer-travel, more progressive ones toward the TTX2. At 130 mm of rear-wheel travel (with a longer-than-stock 55 mm stroke shock, which Guerrilla Gravity condones and tends to be my preferred setup on the Trail Pistol) and a moderately progressive linkage, the Trail Pistol seemed like a bike that could go either way.

The obvious thing to do was to try both to see how they stacked up — so I did just that. And what I found surprised me.

What wasn’t a big surprise was the damper performance — the TTX1 and TTX2 feel predictably similar there, and reminiscent of the TTX22 coil that also uses a largely similar design. The stock tune on both the TTX1 and TTX2 feels a little more firmly damped in compression than average for a “medium” baseline tune on a lot of modern Trail / Enduro shocks but isn’t way off in left field or anything like that. As someone who more often finds modern shocks to be underdamped for my taste than the other way around, the stock tune felt like a great fit for the Trail Pistol — able to provide settings I was happy with while still leaving some headroom to adjust in either direction. Öhlins has a bank of tune options to offer for riders who’d prefer something different from the stock aftermarket one, but the default tune feels like a nice middle-of-the-road option that should work pretty well on a lot of modern bikes, especially for folks who prefer slightly firmer compression damping than average.

The compression adjustment range on the TTX Air shocks isn’t massive, especially in terms of high-speed damping (again, there are only two high-speed settings, plus the climb mode position); the low-speed compression and rebound adjusters have a somewhat wider adjustment range and more resolution available on the adjusters (at 12 clicks each). Provided an appropriate base tune, it feels like a well-chosen range that offers a solid window for adjustment without being so broad that it creates much potential to arrive at an unusably off-kilter setup.

The climb mode on both the TTX1 and TTX2 strikes what I see as a nice middle ground of firmness — definitely more so than any of the many, many iterations of Fox Float X2 that I’ve ridden to date but lighter than the RockShox Super Deluxe; the Fox Float X is a much closer comparison, but if anything I think that one’s a tiny bit firmer than Öhlins shocks. In terms of damping with the climb switch engaged, the TTX1 and TTX2 feel just about the same, but the different air springs make for a noticeable difference in performance — more on that in a minute.

Tune considerations aside, the damper performance of the TTX Air siblings has been quite good. Both have felt consistent and predictable, with no appreciable fading at high temperatures or other such issues, and even at comparatively firm compression settings, neither has felt appreciably harsh or spiky on high-speed hits. Both versions feel tailored more toward being supportive and composed rather than ultra-plush and cushy, but especially for folks who’ve found stock damper tunes — particularly on lighter, more Trail-oriented shocks — to lack in composure under more aggressive riding, the TTX siblings are worth a look.

And that brings us to the point where the TTX1 and TTX2 really differentiate each other — and the area where I was most surprised by their performance: the air springs. The two shocks feel more different on that front than I think I expected going into the review — and also to my surprise, I found that I liked the TTX1 better on the Trail Pistol.

Öhlins has it about right when they talk about the differences in air spring performance between the TTX1 and TTX2 — the TTX1 can be made much more progressive than the TTX2 if you’re so inclined (though on the Trail Pistol, I didn’t need to; I settled into running 4,000 mm3 of volume spacers in the TTX1 and 10,000 mm3 on the TTX2, both well short of the maximum allowed in each). Where the two really stand apart is earlier in the stroke — the TTX2 is more supple off the top, with better small-bump sensitivity and traction, while the TTX1 feels firmer and livelier. That’s not a huge surprise, given the larger negative chamber on the TTX2 in particular, but what it meant for on-trail performance was more interesting.

I already gave the game up by saying that I liked the TTX1 better on the Trail Pistol, but I don’t mean that to be a slight against the TTX2. Rather, the firmer initial stroke of the TTX1 just felt like a better fit for a shorter-travel bike like the Trail Pistol. I’m confident that I’d prefer the TTX2 on most modern Enduro bikes, where the initial sensitivity and traction would be welcome, but on a bike with less total travel to work with, and one that’s meant to be more lively and pop-y rather than super planted and composed in rough sections of trail at speed, the TTX1 felt like the better match.

With the benefit of hindsight, that makes a good deal of sense, but it surprised me at first — I think mostly because I remember the bad old days when air shocks had tiny negative chambers and wildly banana-shaped spring curves with a huge digressive section early in their travel. Bigger air cans, larger negative chambers (and revised frame kinematics to match) have made bike suspension so much better in the last decade or so, and through a certain lens, the bigger TTX2 is the more “modern” shock in that respect.

But really, it’s just a reminder that there’s no one-size-fits-all answer for everything, and it’s to Öhlins’ credit that they offer both versions of the TTX Air because I think that both have their place depending on the bike in question and how a given rider intends to use it. I went into the test not giving the TTX1 enough credit — I think I’d sort of written it off as a lesser-performing option for people who really care about the ~70-gram weight savings, or for bikes where the bigger TTX2 simply doesn’t fit, but that’s absolutely not the case. They’re both good shocks, just ones that do slightly different things well — which is exactly how Öhlins describes them.

The Trail Pistol also pedals slightly (but appreciably) more efficiently with the TTX1 than the TTX2, I think again this is just because the former makes the suspension a little firmer off the top and ride higher in its travel. It’s not a big difference, and wouldn’t be my main reason for choosing one over the other, but it still feels worth pointing out.

Zack: While I didn’t get a chance to spend any time on the TTX2, I was able to log a whole lot of miles with the TTX1 on my personal Propain Hugene. Aside from the fitment issues mentioned above that made air spring adjustments a bit tedious, the shock’s simpler adjustment range made for a pretty straightforward initial setup. I personally don’t mind the tooled rebound and low-speed compression adjusters, though they do add an extra step to on-the-trail adjustments.

The TTX1 took the place of the latest RockShox Super Deluxe, which has a visibly larger air can and volume. With the Hugene’s rather flat leverage curve (i.e., it’s not that progressive), I had to stuff quite a few volume spacers into the Super Deluxe to get adequate support later in the stroke, whereas I ended up running just 4,000 mm3 of volume spacers in the TTX1, given its significantly smaller positive air volume.

Given my experience with Öhlins’ forks, I found it entirely unsurprising that the TTX1 was more firmly damped from a compression perspective, though compared to their forks, it felt like the base rebound tune was a bit lighter, which was good news for my 160-lb self. After some fiddling, I ended up finding myself happy at 205 psi to reach 25% sag, LSC 7 clicks from closed, rebound 7 clicks from closed, and high-speed compression in the “2” position.

Without repeating David’s comparisons to other shocks, I’ll just say that I also found the climb switch to offer a nice balance of firmness without being overly locked out. While the greater support from the TTX1’s compression tune already made for a pretty efficient ride in the open settings, the climb switch was a nice asset for longer road climbs.

As someone who often finds a lot of other shock tunes to be a bit lacking in the compression damping department, I really enjoyed the supportive nature of the TTX1 when the trail turned downward, and I found myself quite comfortable pushing hard in both very wet and very dry conditions that we experienced in the bridge from winter to spring here in the Pacific Northwest. I have many times found myself riding lighter-weight Trail shocks in their middle “trail” settings to gain a bit more support, often introducing some undue harshness to the ride, but the ample compression support from the TTX1 did not require making that tradeoff. While I found myself backing the high-speed compression off to the lighter “1” position in really wet or cold conditions, the more supportive “2” position felt great on higher-speed, rougher trails.

Comparisons

David: Comparing rear shocks is especially tricky because how they’re tuned internally makes such a significant difference to their performance. But, having ridden a whole lot of Float Xs at this point, including on the Guerrilla Gravity Trail Pistol that I used to test the Öhlins siblings, I can say that the Float X is generally lighter damped and more plush feeling, at the expense of some composure and support, especially in high-speed, choppy sections of trail.

In terms of the air springs, the higher-volume TTX2 feels like the more comparable option to the Float X; the TTX1 feels firmer off the top, more progressive deep in its travel, and generally more lively earlier in the stroke.

Zack: Agreed with David here on the Float X generally just feeling more lightly damped. The Float X feels a bit more forgiving than the TTX1 at lower speeds and rides a bit more deeply in the travel. I appreciated the adjustable high-speed compression on the TTX1 as well, whereas the Float X really only offers low-speed rebound and compression adjustments along with the climb switch.

David: I haven’t tried the new Super Deluxe on the Trail Pistol, specifically, but in terms of damper performance, it feels somewhere between the TTX pair and the Float X, in that the Super Deluxe doesn’t tend to be as lightly damped as the Float X (and has more ability to firm up the high-speed damping in particular, since it’s externally adjustable on the Super Deluxe Ultimate). The Super Deluxe also has a wider range of damping adjustments than the TTXs, especially in terms of high-speed compression.

As with the Float X, the Super Deluxe feels like a much higher-volume, less progressive shock than the TTX1, and probably also more so than the TTX2. The Super Deluxe is a bit more plush and sensitive off the top; the TTX2 is more damped and less lively in general.

Zack: Compared to the 2023 Super Deluxe Ultimate that I was initially running on my Propain Hugene, the TTX1 feels notably firmer off the top. Where the very linear leverage curve of the Hugene had me stuffing quite a few volume spacers into the Super Deluxe, the smaller air volume of the TTX1 required far fewer. The Super Deluxe is likely the more versatile option given that volume spacers can be added to both the negative and positive chambers, which does open up some ability to reduce negative volume and replicate the more peppy feel of the TTX1, and it also has a greater damper adjustment range. The larger negative volume of the Super Deluxe also opens the option of running fewer spacers and higher pressure to increase mid-stroke support from the air spring, whereas the TTX1 offers a bit less in that area. The TTX1 still feels like it offers a bit more compression support from stock, which I appreciated.

David: I’ve ridden the Öhlins air and coil offerings on very, very different bikes, but they do have some similarities in terms of damper performance — which makes sense, given their fairly similar designs there. The TTX2 is by far the more linear, coil-like option of the two air shocks, but still feels significantly firmer off the top than the TTX22, and does give up some midstroke support as well. The TTX22’s small-bump sensitivity and traction are better, but the TTX2 feels more lively, saves some weight, and has all the typical upsides of an air shock when it comes to tunability and so on.

David: Once again, I’ve ridden the TTX Airs and the Aria on very different bikes, but I’m confident in saying that the Aria’s spring curve is more linear and coil-like than that of the TTX2 (and the TTX1 to an even greater extent), with a more plush feel in the early part of the travel and more midstroke support; both versions of the TTX Air, especially the TTX1, can be made more progressive deep in the stroke if that’s what you’re after.

It’s tough to say much about damper tunes here since even aftermarket versions of the Aria are delivered with a custom tune for the bike and rider in question, but it feels like it’s got a wider range of high-speed compression adjustment but a tighter range on the low-speed compression and rebound (and finer resolution on all three) than the TTX2.

In very broad strokes, I think it’s fair to think of the TTX2 as landing between the TTX1 and the Aria in terms of spring curves and everything that m means for ride quality. And we’ll have a lot more to say about the Aria in our full review, coming soon.

Who Are They For?

David: Both versions of the Öhlins TTX Air are going to be best suited to folks who prefer a more damped, more composed feel from their suspension and are willing to forgo a little small-bump sensitivity and plushness to get there. That’s not to say that the TTX Airs are particularly lacking in that regard; rather, they just favor more supportive, heavily damped setups, and for a lot of folks, especially those who are heavier and / or more aggressive and tend to ask a lot of their suspension, that’s going to be a good thing.

The differences between the TTX1 and TTX2 really come down to the air spring. The TTX1 feels more supportive and lively off the top part of the travel and more progressive deep in it, but gives up some support through the middle part of the stroke; the TTX2 feels more linear overall. That makes the TTX1 a generally better fit for shorter-travel bikes (where the liveliness and pedaling support off the top are particularly worthwhile) and the TTX2 the way to go for longer-travel, more progressive bikes for its better midstroke support and small-bump sensitivity.

Zack: While I can’t speak for the TTX2, the TTX1 really feels like a unique offering for shorter-travel Trail bikes that are often designed around lower-volume air shocks. Shorter-travel bikes designed around lighter-weight shocks can feel a bit vague and unsupportive when paired with an overly large-volume air shock or coil, and the TTX1 offers an incredibly capable damper packaged with an air spring that is tailor-made for those sorts of bikes.

The tradeoff is that the TTX1’s more aggressive damper tune and firmer feel off the top can be a little more fatiguing on long rides compared to some of its competitors. It’s a shock that I’d steer more aggressive or heavier riders toward in a heartbeat, but lighter riders or folks prioritizing comfort over all-out descending performance might find the TTX1 to be a bit aggressive for their tastes, at least with the stock damper tune.

David: Yep. I really want to underline Zack’s point that the TTX1 feels like a uniquely good option for riders on less-progressive, shorter-travel bikes that benefit from a smaller-volume air can, but who find that most other lower-volume options lack the damper support and adjustability that they’d like. That maybe isn’t the biggest swath of riders ever, but I’m sure there are plenty of folks in that camp — and I know I’ve been there myself on certain bikes.

Bottom Line

Öhlins’ approach of offering two very different air cans on the same shock isn’t entirely novel — RockShox has done something similar with the Super Deluxe over the years, for example — but the TTX1 and TTX2 feel starkly different, in a way that I think makes each well suited for different bikes and rider preferences. Both are on the more firmly-damped, more composed, and stable-feeling end of the spectrum (at least with their stock damper tunes), and especially for folks who find lighter Trail bike shocks to be lacking on that front, they’re compelling options.

Great article!

I’ve always been into Blister for the skiing but love to ride as well and David Golay is a terrific addition.

Look forward to more from Zack Henderson, as well.