Formula Belva Fork

Travel Options: 170 and 180 mm

Wheel Size Option: 29’’

Available Offset: 43 mm

Stanchion Diameter: 35 mm

Stated Weight: 2,370 g / 5.22 lbs

Stated Axle-to-Crown Height (180 mm travel): 585 to 595 mm

MSRP: €1,850 / $2,150 CAD (USD pricing TBD)

Blister’s Measured Weight: 5.31 lbs / 2,410 g

Test Locations: Washington, British Columbia

Reviewers:

- Zack Henderson: 6’, 160 lbs / 183 cm, 72.6 kg

- David Golay: 6’, 170 lbs / 183 cm, 77.1 kg

Test Duration: 2.5 months

Intro

The bike world has mostly settled on using dual-crown forks for DH bikes and single-crown ones for everything else these days. Over the years, though, there have been a few attempts to make lighter-weight dual-crowns that are versatile enough to use outside of lift-served trails, from the RockShox SID XL of the late 1990s to the Specialized Future Shock, Mojo MORC 36, and others.

And, to their credit, there are some very real advantages to a dual-crown layout. For one, it’s much easier to make a fork stiffer fore-aft when you have a second crown to work with. Dual-crown forks can also adjust their ride height independently of their travel setting (via bolt-on crowns), and direct-mount stems are often lighter than their conventional counterparts, don’t run the risk of slipping or coming out of alignment, and are often stiffer and more precise in how they steer, too.

I’ve been calling for companies to offer lightweight, Enduro-oriented dual-crown forks for years now, and Formula has (finally, after years of prototypes being sporadically spotted) answered with their new Belva fork.

Here’s how Formula describes their rationale for the Belva:

“With bikes becoming more capable and e-bikes gaining in popularity, your suspension needs to work harder than ever. As engineers, we believe the best solution to building a stiffer, long-travel fork is by using a dual-crown design.

Most fork flex occurs at the crown steerer unit (CSU), regardless of stanchion size. A dual-crown design avoids this — and the associated creaking — by centering the stiffness around the headtube.

Absolute stiffness is not everything, though. Using our proven Selva lowers, the Belva can flex where it is most needed. With the dual crown and a direct mount stem, you can have laser-sharp steering and confidence-inspiring stiffness, combined with trail-hugging traction and comfort.”

So, that’s their answer to the “why” behind the Belva. What about the “what” and “how”? Let’s get into the details:

The Design

There’s a lot of interesting stuff going on with the Belva, beyond just its dual-crown layout. Many of its details are shared with Formula’s single-crown Selva fork, rather than being brand new for the brand. But the Belva still stands out from the rest of the market — so let’s see what they’ve come up with.

Chassis

We’ll start with the chassis: the Belva shares its lowers (and thus its 35 mm stanchion diameter) with the Formula Selva, but the Belva gets a dual-crown layout with forged crowns and a tapered steerer tube. The latter aspect is unlike most dual-crown DH forks, which stick with a straight 1.125’’ steerer tube. The Belva’s crowns are notably svelte-looking, with a lot of cutouts in the upper crown in particular, and despite the dual-crown layout, Formula’s stated weight for the Belva is just 2,370 grams — comparable to that of the single-crown RockShox ZEB, Fox 38, and EXT Era, for example.

For now, Formula is only offering the Belva with a 110 x 15 mm axle and compatibility for 29” wheels, despite having options for 27.5’’ wheels and / or a 20 mm axle on the Selva. The Belva gets 43 mm of offset and is offered with 170 or 180 mm of travel. The Belva’s axle-to-crown height is 585 to 595 mm at 180 mm of travel (and 575 to 585 mm at 170 mm travel, adjustable due to the dual-crown layout).

That’s roughly in line with most modern single-crown forks at the same travel setting; e.g., a 180mm-travel 29er RockShox ZEB comes in at 596 mm, and a Fox 38 with the same specs is 593.7 mm. That makes the Belva a bit taller (relative to the amount of travel) than most dual-crown DH forks, which tend to run a little shorter than single-crown ones at the same travel. Given that Formula is marketing the Belva specifically as an Enduro fork, that makes sense — it’ll swap onto a bike that’s meant for a 170- or 180mm-travel single crown without changing the ride height much, while affording a little room to tinker.

The Belva is offered in black or Formula’s signature purple, and its lowers get post-mount tabs for a 180 mm brake rotor, which Formula condones adapting up to a 220 mm one if you’re so inclined. The Belva’s axle uses Formula’s “Integrated Locking System” (ILS) quick-release lever, which can be removed from the axle if you’d rather do things with an Allen wrench and save a few grams.

Damper

The Belva’s damper uses a similar design to that of the Selva, just reconfigured for the dual-crown chassis. It gets an external rebound adjuster, a single compression knob, and a lockout lever with adjustable threshold for how firm the lockout is. The compression knob is tool-free with 12 clicks of adjustment; the rebound knob gets 18. The threshold dial for the lockout uses a tooled adjuster on top of the fork leg, next to the compression knob and lockout lever.

It’s not super common to see a lockout lever on a longer-travel fork these days, but it’s not unheard of either; where things really start getting interesting is Formula’s “Compression Tuning System” (CTS).

In short, the Belva (and the Selva) feature swappable compression-valve assemblies that allow the user to swap in one of eight different base tunes to fundamentally alter the damper performance.

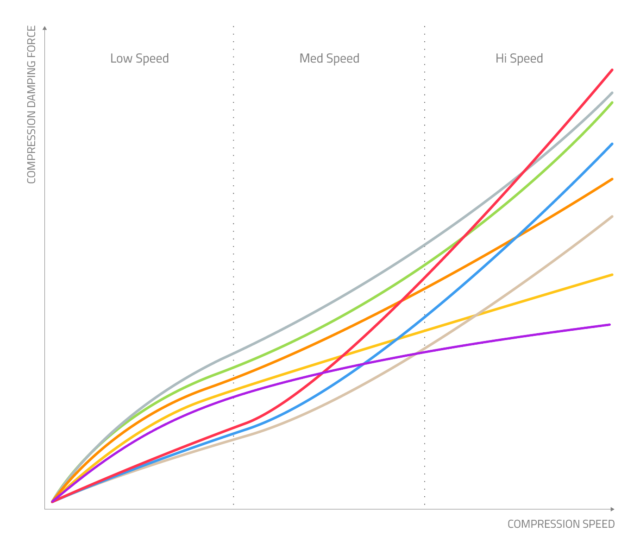

In very broad terms, Formula offers CTS cartridges with two general compression damping curve shapes. There are five options for a lightly digressive curve with differing levels of overall damping (purple, gold, orange, green, and electric blue, in order of lightest to firmest damping); those get more linear as you work your way up in order of overall firmness. And then there are three with a substantially progressive damper curve (silver, blue, and red).

[By a “linear” damper curve, we mean that the amount of compression damping increases in a more or less straight line as the speed at which the damper is compressing increases; a “progressive” curve means that the damping force increases more rapidly at higher shaft speeds than it does at lower ones. A “digressive” curve — as seen most notably on the purple and gold CTS valves, below — builds damping force relatively quickly at lower shaft speeds, but the rate of increase tails off at higher ones.]

You can see Formula’s published damper curves for the various options here:

Formula says the swap can be done in about five minutes, without even removing the fork from the bike, and without needing to bleed the damper. You could even do it trailside if you really want to, though they don’t recommend that, due to the risk of getting dirt in places it doesn’t belong. Realistically, it’s probably more of a swap that folks will make when finding their preferred initial setup, or maybe when changing riding locales to somewhere with very different terrain, but it’s an intriguing way to make (semi) custom valving more accessible for more folks.

[Formula has a video demonstrating the swap if you’re curious. It also opens with the wildest safety disclaimer I’ve seen in recent memory. I won’t spoil it beyond that.]

The Belva ships with the gold CTS cartridge installed; additional cartridges are available for about $65 each if you want to experiment.

Spring

Formula offers the single-crown Selva in both air- and coil-sprung configurations but has once again paired the offerings down for the Belva, which is offered with an air spring, only.

Formula describes the Belva as using a “single air” spring. This is in contrast to their “dual air” Selva R, with independently adjustable positive and negative spring pressure, or the “triple air” Nero R DH fork, with a dual positive air spring and adjustable negative one.

Its “single air” arrangement means that the Belva uses a coil negative spring rather than a more typical self-equalizing air one. They’ve been using a similar layout in the Selva S for a while now, and say they’ve hit on a design that works well for folks at a wide range of rider weights (and thus air spring pressures).

The Belva also uses Formula’s “Neopos” volume spacers, which are conceptually similar to those used by Fox and RockShox, among others, except that the Neopos spacers are made from a compressible foam material, rather than rigid plastic. The idea is that the Neopos spacers take up more volume inside the air spring earlier in the fork’s stroke when the pressure in the positive spring is lower, and then the Neopos spacers compress deeper in the stroke as pressure on them increases, reducing the amount of ramp-up effect deep in the travel as compared to a standard rigid volume spacer.

The goal is to offer more midstroke support without making the fork keep ramping up deeper in its stroke, not unlike the thinking behind dual-positive air spring designs. (Check out our review of the Manitou Mezzer Pro for a rundown on what we’re talking about there.) But there’s another, more subtle difference in how Neopos works.

In short, air springs don’t perform entirely consistently depending on how fast they’re compressed — unlike coil springs, where the force needed to compress them is just a function of their displacement. As air is compressed, it heats up, which in turn increases the pressure in the system; that effect is moderated at lower compression speeds and increases at higher ones. An air-sprung fork is actually stiffer if you compress it quickly than if you do so more slowly, and therefore also returns more energy on rebound after a fast compression than on a slower one.

Formula says that the Neopos spacers moderate that effect by expanding at a constant rate, no matter how quickly or slowly they were compressed in the first place (like a coil spring, rather than an air one), making for a more consistent and predictable rebound feel.

Warranty

The Belva is covered by Formula’s new 10-year support promise — a guarantee that they’ll offer on parts and service for everything in their lineup for at least 10 years. Everything they’ve made since 2017 is covered by the support promise, and the Belva also gets a two-year warranty, which can be transferred to subsequent owners.

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) How does the Belva chassis feel, given its dual-crown layout and impressively low weight?

(2) What about the Belva’s spring and damper designs? We haven’t ridden any of Formula’s current fork offerings, so how do they perform on the trail?

(3) And will we see more widespread adoption of dual-crown forks for Enduro bikes, especially as eMTBs become more common? This question pertains both to other fork manufacturers following suit, and to frame companies condoning running dual-crown forks on their non-DH bikes.

FULL REVIEW

David Golay (6’, 170 lb / 183 cm, 77.1 kg): I’ve been very, very excited about the Belva ever since photos of prototype versions first surfaced several years ago. My journey with dual crown forks on Enduro bikes started when I built up my Nicolai G16 — the first truly modern Enduro bike I owned — back in 2017. In those days, the Fox 36 was about as stiff as mainstream single-crown forks got, but at 170 mm travel and on a bike with a 62.5° headtube angle, its fore-aft stiffness felt woefully inadequate, most notably under heavy braking in steeper terrain.

So I lowered a Fox 40 to 180 mm travel (by way of a custom shortened air shaft) and slapped that on — and it was a massive, massive improvement. I didn’t mind the added weight much, and the limitation to the turning radius was mostly a non-issue, too. There’s a reason DH bikes use dual-crown forks, and I didn’t see a good reason for Enduro bikes not to get a lighter, pared-down version that was better suited to their travel range and saved a little weight in the process.

Formula clearly agreed, teasing prototype photos of the dual crown Belva for quite a while, but in the meantime, a new class of extra-burly single-crown forks cropped up, with the Fox 38, RockShox ZEB, Öhlins RXF 38 m.2, and others trying to fill the void from the opposing side. So does that mean Formula is onto something uniquely better, or just unique? After a few months on the Belva, we’ve found that to be a trickier question to answer than you might expect.

On the Trail

Zack Henderson (6’, 160 lbs / 183 cm, 72.6 kg): Formula suspension is a rare sight here on the West Coast of the US, and the unique dual crown layout of the Belva drew far more attention at the trailhead than I expected. While the machining details make it rather attractive, most of the attention was more along the lines of incredulity, often met with something like “man, interesting choice running a Downhill fork around here”.

The funny thing is, unless you’re looking down at the extra crown and direct mount stem, the Belva feels entirely unobtrusive on the trail. David mentioned this in his Flash Review, but I ran into absolutely zero issues with the turning radius while navigating technical switchback climbs — perhaps the biggest concern I had going into our testing. Then there was the weight — it’s not a featherweight at 2,410 grams, but that’s actually right in line with many of the burly 38 mm stanchion single crown Enduro forks.

Despite weighing right in the same ballpark as its single crown peers, the Belva is noticeably stiffer fore-aft. While single-crown forks have increasingly beefy crowns, the relative abundance of creaking steerer tube issues highlights just how much force is being put through the steerer and crown interface without any additional support above it. The Belva’s dual crown layout means that the stanchions are able to provide additional support along the full length of the bike’s headtube to the upper crown. This should mean that creaking steerer tubes are entirely a non-issue, but it also means that the Belva’s relatively svelte-looking crowns can still deliver huge stiffness gains beyond a single crown layout.

The impacts of that additional stiffness are definitely an advantage on rougher tracks. There’s a more direct feeling of bump forces being transferred into the suspension motion itself versus trying to fold the rear wheel under the bike. Torsional stiffness is more of a wash with other Enduro forks, mostly down to the beefy 38 mm stanchions used on other single crown forks versus the Belva’s lighter weight 35 mm stanchions, meaning that steering still feels familiarly precise. It also means that compared to Downhill forks like the notoriously stiff Fox 40, the Belva still feels a bit more compliant and less likely to skip off line and lower speeds. All in all, while modern single-crown forks are certainly no slouch in the stiffness department, the Belva feels sturdier.

David: Seeking more fore-aft stiffness was the biggest thing that kicked off my Enduro dual-crown fork journey the better part of a decade ago, and while the burliest single-crown forks of today are a lot better than the options from that era, the Belva is very appreciably more stout fore-aft than any single-crown fork I’ve ridden. Of course, stiffness of bikes / bike parts isn’t always a more-is-more situation — I consistently prefer 31.8 mm diameter handlebars over 35 mm ones, for example, and we’ve seen a lot of instances of World Cup DH racers experimenting with ways to make their frames less stiff, from Amaury Pierron running a custom steel chainstay assembly on his Commencal Supreme, to Danny Hart’s mechanic machining away big chunks of the rear end on his GT Fury.

But if there’s such a thing as a fork that feels too stiff fore-aft for my taste, I’ve yet to experience it. The sensation of having the front wheel tuck under the bike when subjected to heavy braking on a steep pitch isn’t a pleasant one, both because of the chattery feel you get as the fork springs back and forth, and because that fore-aft bending is especially prone to making the fork bind up and move less freely, hampering bump absorption and traction. The Belva feels great there.

The Belva doesn’t feel as ultra-stiff torsionally as the RockShox BoXXer or (especially) the Fox 40 but it’s also 400+ grams lighter than either and is plenty precise for my preferences on a ~160mm-travel Enduro bike. I’m in full agreement with Zack that a little bit of torsional flex can be helpful for maintaining grip and tracking as opposed to just pinging off every little off-camber obstacle, and the overall chassis feel of the Belva works really well for my tastes on a bigger Enduro bike that’s going to be pushed quite hard but still sees overall lower / more varied speeds than a dedicated DH bike. I love the balance of weight and stiffness that Formula has chosen for the Belva chassis.

The turning radius continued to be a total non-issue for the rest of my testing, too, including after moving it from the slimmer-tubed Chromag Lowdown to the chunker RAAW Madonna. I did hit the bumpers on… I think literally just one specific uphill switchback that I can think of, and it’s one that’s tight enough that I’m quite hit-or-miss at cleaning it on an Enduro bike with a single-crown fork anyway. I didn’t mind the Belva’s modest limitation there one bit.

Zack: Of course, a fork needs more than just a good chassis to work well, and fortunately, Formula was mostly able to deliver on the spring and damper front as well. Starting with the damper side of things, I completely agree with David’s thoughts from the Flash Review around the blue CTS valve being my personal happy place. I generally prefer relatively high levels of high-speed compression damping, and the blue valve offered way more of that than the others we received (gold and violet). I still found some situations where the fork felt a bit less poised than I’d like, mostly in particularly harsh high-speed compressions where it felt a bit dive-y at times, and I’d sure like to try the red CTS valve or the new Josh Bryceland version that supposedly brings damping levels up even further. Unfortunately, we couldn’t make that happen during the term of the review, but the blue CTS unit was supportive enough in most situations. It’s especially cool that the CTS valve swap is so incredibly easy, meaning that tuning can be done in literally a minute or two at home rather than requiring a trip to the suspension service center.

David: One of the big questions I had about the Belva going into our testing was just how well the CTS system would work, and if it would feel like it imposed any notable limitations on the damper design. The idea is a cool one — and, like Zack, I found it to both be very easy to swap and to make a very real difference to the Belva’s performance — but the CTS valves are quite small, and I couldn’t help but wonder if making them so easy to swap would have any apparent downsides. Would the Belva’s damper feel spiky on higher-speed impacts, as if it couldn’t flow enough oil, or simply be stuck with a lower-performing damper design in order to package the swappble CTS valves?

It really doesn’t feel like it. I was frankly pleasantly surprised by how well the system works. The different valves make a very clear difference to the performance / feel of the fork, and I didn’t experience any of the spikiness or harshness that I feared I might find at higher shaft speeds due to the small size (and presumably not-massive flow capacity) of the CTS valves. It works well.

Zack: While I’m mentioning the damper performance, I should also say that the rebound side of things had quite a bit of range and was easy to dial in for my preferences. I do, however, think that Formula could forego the lockout dial and lockout threshold adjuster on the top of the damper — it makes for a crowded-looking top cap, but more than that, it just adds unnecessary clutter and complexity that most riders are unlikely to use on a fork like this.

David: Fully agreed. I really don’t feel the need to have a lockout on a 170mm-travel Enduro fork and would be happy to forgo it. If dropping the lockout would open up the room to have a separate high-speed compression adjustment, even better, though that might be wishful thinking on my part — Formula’s DH fork, the Nero, has separate low- and high-speed compression adjusters, but no swappable CTS valves. Having the swappable CTS valves definitely mitigates the need for a separate high-speed compression adjuster anyway.

Zack: I think a big part of the reason I found myself curious about even higher damping levels than the blue CTS valve could provide was down to the air spring. In the simplest terms, it feels like an air spring from 5-6 years ago rather than the impressively linear ones that many brands have managed to develop more recently. Formula’s reliance on a coil negative spring means that the fork’s negative spring isn’t really adjusting to higher pressures in the positive chamber, and I found that straying much beyond 70 psi in the positive chamber could start to introduce a lot of feedback in the earliest part of the stroke. This didn’t appear to be down to friction but instead felt like the characteristic “hump” in the early part of an air spring curve that larger negative springs have been designed to overcome. This also meant that the air spring could feel a bit firm at the top before falling off a bit into the midstroke, making things a little bit less predictable coming from more linear air spring designs.

Lighter riders are less likely to notice the downsides of the less-than-adequate negative spring, whereas bigger riders running more pressure will likely find themselves dealing with an overly firm and slightly unpredictable early travel.

David: The Belva’s air spring definitely feels a bit different from most of the modern crop of modern designs with large-volume negative air chambers. It’s not that the coil negative spring can’t balance forces at topout across a fairly wide range of positive spring pressures — the initial breakaway feels smooth, and topout is controlled well enough until the positive air spring pressure is set much higher than I had any need to at 170 lb / 77.1 kg riding weight (in stark contrast to the feeling of a more conventional design when the positive and negative chambers aren’t equalized properly).

[The Belva’s exact travel and axle-to-crown height changes slightly based on the positive spring pressure since higher pressures will preload the coil negative spring more and thus extend the fork a few extra millimeters, and vice versa. It’s hard to measure exactly, but our nominally-170mm-travel Belva seems to hit 170 mm of actual travel at about 63 psi; the ~68-69 psi that I wound up running adds 3 or 4 mm to that figure. But the dual-crown layout of the Belva affords plenty of leeway to dial in the axle-to-crown height by moving the lower crown up or down as desired.]

But the early part of the Belva’s travel does feel a bit firmer / more supportive than most modern forks, before giving way to a softer portion in what feels like roughly 30% of the way into the stroke. I wouldn’t call the sensation harsh — the Belva still moves freely from topout — but it does transmit more feedback early in the travel than the Fox 38 Grip X2 or (especially) the RockShox ZEB. The Belva also feels like it gives up a little bit of traction on really small bumps for it, though I mostly didn’t find that to be a big issue — the front wheel might deflect a little more than I expected on super small chatter, but the Belva opened up and handled impacts that might have been big enough to cause a real loss of grip fine.

Like Zack, I found myself running a bit lighter spring settings and more compression damping than I might have otherwise to minimize those tradeoffs — and found the Blue CTS valve to get me most of the way to where I wanted to be. The added high-speed compression support that the Blue valve brought over the stock Gold one helped quite a bit with composure in faster, choppier sections of trail, and the reduced low-speed compression damping of the Blue valve reduced the sensation of a firm, super-supportive early part of the travel giving way to a soft midstroke that I described earlier.

That feeling wasn’t gone, though, and I think it’s down to the spring design far more than it has anything to do with the damper. I was able to get the whole package to a position that generally worked pretty well for me, but the limitations of the spring design felt like they reduced the overall useful tuning window somewhat. I’d have loved to be able to run a slightly firmer spring rate overall, but the hit to early sensitivity when doing so was greater than I would have liked.

Formula’s take is that their “single air” spring is simpler to set up than their more complex double and triple air versions, and while I haven’t had the opportunity to ride either of those variants (in one of their other fork models — again, the Belva is only offered with the single air spring, at least for now), I don’t doubt them on that point. But I also think that a somewhat unconventional fork like the Belva is likely to appeal to more tuned-in, tech-oriented folks who wouldn’t be as put off by the extra complexity as more set-and-forget types, and given the performance tradeoffs that the single air arrangement seems to introduce, I’d love to see one of the more sophisticated spring variants offered in the Belva. Given that Formula has historically offered many of their forks with multiple spring options, I wouldn’t be surprised to see such a variant down the line, but we’ll just have to wait and see.

Bottom Line

Zack: The Belva will inevitably appeal to folks who aren’t afraid to try something exotic and niche, but that’s selling the fork a bit short. There are absolutely merits to the dual crown design, and the fact that I didn’t really notice any inconveniences while climbing left me wondering why most other brands have resisted dabbling in a lightweight dual crown design. It may very well be the reputation of dual crowns on Enduro bikes being a quirky choice, but the solid chassis and highly tunable damper performance of the Belva make a whole lot of sense once you get past the aesthetic differences. It’s a good fork as it is, but if Formula can deliver a slightly more contemporary (linear) air spring characteristic, they’ll have something extremely special on their hands.

David: Fully co-signing Zack’s take here. The Belva chassis is great, the damper works well (and the swappable CTS valves are a cool touch) but the single-air spring doesn’t feel as supple off the top as I might hope for, especially at higher air pressures. It works alright, but I’d be very curious to try a version of the Belva with one of Formula’s more elaborate dual (or even triple) air springs. There’s no option for those in the Belva (yet?) but if Formula can smooth out the early part of the spring curve it’d turn a good fork into a great one.

This fork make so much sense to me on an enduro bike. There is basically no downside. I’m about 200lbs though so I don’t know if that air spring is going to be good for me.

Wonder if the latest 2025 air spring in the Selva will be incorporated in the Belva… or a coil option :)