Suspension 101: Basic Concepts and Definitions

If you know very little about suspension and want to get your head wrapped around the basic concepts and definitions, you’ve come to the right place.

This first installment of our Bike Suspension 101 defines the components that make up a suspension system, from the fork to the pivot, and also lays out some of the basic differences between cross-country, trail, all-mountain, and downhill bikes.

We’ll be following up with more advanced discussions in subsequent articles, including a specific discussion of how to set up your suspension, and an explanation of what’s really going on in there.

Check back next week for the following article—a detailed look at the different suspension designs on the market.

The Idea Behind Suspension

The basic premise behind suspension is three-fold:

(1) It makes things more comfortable; the shocks absorb bumps so that your body doesn’t have to.

(2) It helps you keep your bike under control—suspension helps your wheels accurately track the terrain, rather than bouncing and deflecting off of it.

(3) It helps the rear wheel stay planted on the ground so that, when you’re pedaling, your efforts actually make the bike move forward.

Mountain bikes basically come in three flavors: full suspension, front suspension, and rigid. Full suspension bikes have a suspension fork as well as a rear shock. Front suspension bikes (usually called hardtails) have a front suspension fork, but no rear shock. Rigid bikes don’t have suspension forks or rear shocks.

Glossary

These articles aren’t going to do you much good if you’re not familiar with some of the basic terms to talk about suspension. (If you already know this stuff, feel free to skip ahead.)

Fork: The thing on the front of your bike that your front wheel attaches to. This could mean a suspension fork (that has a shock built into it) or a rigid fork (that doesn’t have any suspension gadgetry). For the purposes of this article, we’re only talking about suspension forks.

Shock: The suspension unit that compresses and rebounds. Generally, the term shock is used to refer to the rear suspension unit on a bike.

Pivot: A point on a suspension frame wherein a portion of the frame rotates on a bearing or bushing to allow for the suspension movement.

Linkage: The pieces of the frame between the pivots.

Stiction: Static friction, usually associated with seals on a shock. It’s friction that makes a shock feel sticky, particularly at the beginning of its travel.

Travel: The amount that a suspension fork or suspension frame can compress.

Stroke: The amount that a rear shock can compress, which is distinguishable from how much a frame can compress—the frame’s travel is a function of the leverage ratio on the shock and the shock’s stroke.

And take note—While understanding the relationship between travel, stroke, and leverage ratios is important, it’s the discussion of travel that really matters when you’re thinking about bikes. Knowing the stroke on a bike is practically useless, unless you’re looking to replace the rear shock.

Damping: A system that controls the rate of movement in a fork or rear shock, usually via oil passing through ports or openings.

Ok, with those key terms under your belt, let’s move on to…

The Pros and Cons of Suspension

Adding suspension to a bike is always a trade off. You get increased comfort and control, but it adds weight and complexity, and it can make the bike pedal less efficiently.

That said, modern suspension is efficient enough, lightweight enough, and reliable enough that, for many people, the benefits of suspension outweigh the downsides.

- Weight / Maintenance

The weight and complexity issues are fairly straightforward—the more shocks, pivots, and bits of linkage you have on a bike, the harder it will be to keep the weight down.

Those pivots and shocks also require maintenance to keep everything running smoothly, so that’s just one more thing you have to pay attention to.

- Efficiency / Inefficiency

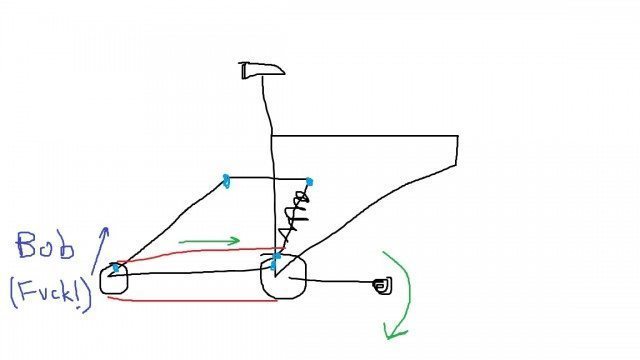

The efficiency issue largely has to do with “bobbing” suspension. With most frame designs, force on the drivetrain will have some effect on the suspension.

Basically, when you mash on the pedals, part of your power is going into making the bike go forward, and part of it goes into making the suspension compress. Generally speaking, this is a bad thing—you want all of your power going into making the bike move forward.

Frame and suspension designers have come up with two ways to battle this inefficiency. The first is through frame design—lots of full suspension bikes position their linkages in a way that is designed to resist pedaling forces.

Some suspension designs do a better job at this than others, which is why this area sees a fair amount of development and competition among brands. A basic discussion of different suspension linkages will be included in next week’s article.

The second way to combat these inefficiencies is via the rear shock. Basically, the shock can be made to be fairly stiff so that the relatively small amount of force that comes from pedaling won’t make the shock compress.

The trick, of course, is to make a shock that doesn’t allow the suspension to bob from pedaling forces, but still allows the suspension to work when it hits a bump. Suspension makers go about this in a couple of different ways, most of which include adjustments to the compression damping—again, look for our forthcoming Suspension articles.

A Side Note on Units

Some countries talk about suspension in metric units, and some talk about it in inches. I’m going to try stick to metric, because inches are stupid. But in reality, suspension and frame manufacturers are all over the place in terms of what units they use to describe their products.

Using metric units might make bald eagles cry, but it still makes more sense to measure bald eagle tears in milliliters.

Amount of Suspension / General Bike Categories

After the initial question of “suspension vs. no suspension,” there next comes the question of “How much suspension?”

As bikes became more efficient, the amount of suspension increased. It used to be that pedaling on a long travel bike was a Sisyphean effort, reserved primarily for hearty Canadians that liked to huck to flat. They were heavy and inefficient. (The bikes, not the Canadians.)

With modern suspension and frame designs, the uphill struggle is no longer the stuff of legend. That said, shorter travel bikes are generally more efficient just because they can be made lighter, so any suspension bob will be less noticeable.

Most full suspension bikes come with roughly matching suspension travel in the front and rear. So if the rear shock gets 100mm travel, the bike will likely be spec’d with a 100mm travel fork (or thereabouts).

- 80mm – 100mm Travel: “Cross Country” Bikes

The smallest amount of suspension that is commonly available these days is around 80mm. Most modern full-suspension bikes that are designated for cross country (i.e. designed to go uphill fast) are coming with 100mm-travel suspension. Many hardtails available these days are coming spec’d with 100mm forks.

- ~130mm Travel: “Trail” Bikes

From there, suspension steps up somewhat incrementally. Around 130mm travel is what most companies would call a “Trail” bike. These are generally designed for all around riding. They climb pretty well, and they descend pretty well. 130mm is also about the longest travel fork that you’ll commonly find on a hardtail.

As noted above, bikes that are designed for rougher trails generally have more suspension travel. Beyond 130mm travel, most people find that the benefits of the hardtail are outweighed by the roughness of the trail.

- 150mm – 160mm Travel: “All Mountain” Bikes

Around 150-160mm travel is generally what bike companies are calling “All Mountain” bikes. These are designed to go down rough trails quickly, while still maintaining at least some degree of uphill friendliness.

- ~200mm Travel: “Downhill” Bikes

Most downhill bikes come with around 200mm of travel. While pedaling efficiency is still important, most downhill bikes aren’t built with any amount of uphill in mind—the frame and suspension designs are focused on making the bike go down rough trails as fast and as smoothly as possible. A chairlift or a pickup truck is the assumed means of getting to the top.

And just to make sure we’re on the same page—the above descriptions of the different travel categories are generalizations. And, in case this wasn’t obvious, there are lots of other differences between the various categories of bikes beyond just the amount of suspension.

Aside from having twice as much travel, a downhill bike is going to handle completely differently from a cross country bike—the amount and type of suspension is just one of many differences.

Ok, that’s enough for now. If you’re ready to read on, check out Suspension 101: Designs which covers the different suspension designs on the market and discusses the pros and cons of each one.

thanks, very helpful

thanka a lot for your time to write this Article …:-)

Good day,

I am an off road driver and would like to know:

1\ The definition of a long travel suspension?

2\ When a shock travels what is the distance to be regarded as a long travel shock?

3\ Is a coil over shock also classified as a long travel shock

4\ Does one see an off road suspension also as long travel?

Should you not have the answer for me, can you please guide me?

Looking forward in hearing from you.

Regards