Yeti SB160

Wheel Size: 29’’

Travel: 160 mm rear / 170 mm front (compatible with up to a 190mm-travel fork)

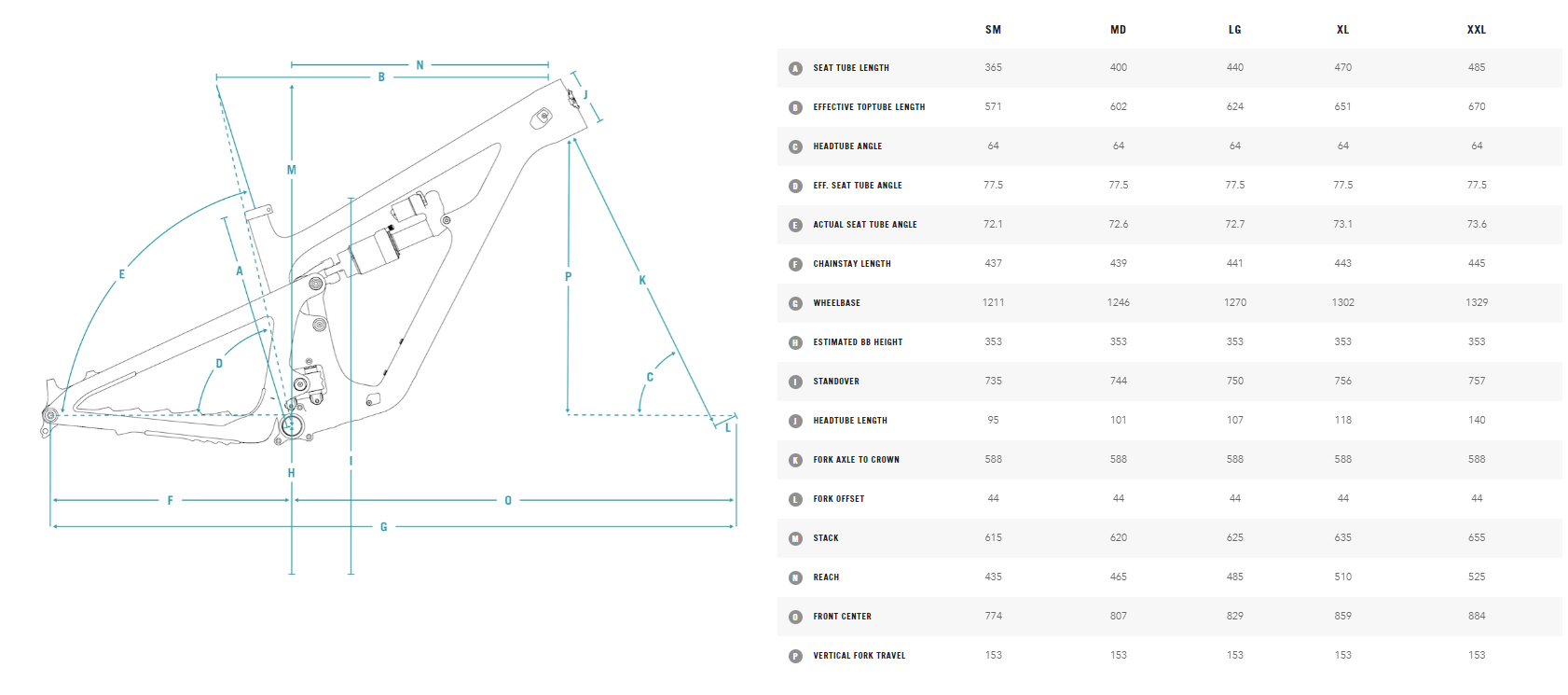

Geometry highlights:

- Sizes offered: S, M, L, XL, XXL

- Headtube angle: 64°

- Seat tube angle: 77.5°

- Reach: 485 mm (size Large)

- Chainstay length: 437 mm to 445 mm (2 mm increments per size)

Frame material: Carbon Fiber

Price:

- Frame w/ Fox Float X2 Factory shock: $5,000

- Complete bikes: $6,700 to $10,800

Blister’s Measured Weight: 34.4 lb / 15.6 kg (SB160 T1, size Large)

Test Locations: Washington, British Columbia

Reviewer: 6’, 175 lb / 183 cm, 79.7 kg

Test Duration: 3.5 months

Intro

Yeti just overhauled the core of their lineup, with the new SB160, SB120, and SB140 replacing the SB150, SB115, and SB130, respectively. First up is the biggest bike in the range, the SB160 Enduro race bike, and we’ll have more on the other new models coming soon.

The Frame

As you’ve probably guessed, the SB160 has 160 mm of rear wheel travel, up 10 mm from the SB150 that it replaces. That brings it more in line with the modern crop of Enduro bikes that it’s competing against, both on the EWS circuit, and on the bike shop sales floor. The SB150 came out back in 2018, and while it’s aged quite well for a bike that’s been on the market for so long — its geometry was notably aggressive at the time that it launched — the prevailing trends in Enduro bike design have moved longer and slacker, and suspension travel has crept up to go with it. Yeti makes it clear that they’ve designed the SB160 to be an EWS-ready race bike first and foremost, and the updates that they’ve made to the frame seem sensible with that goal in mind.

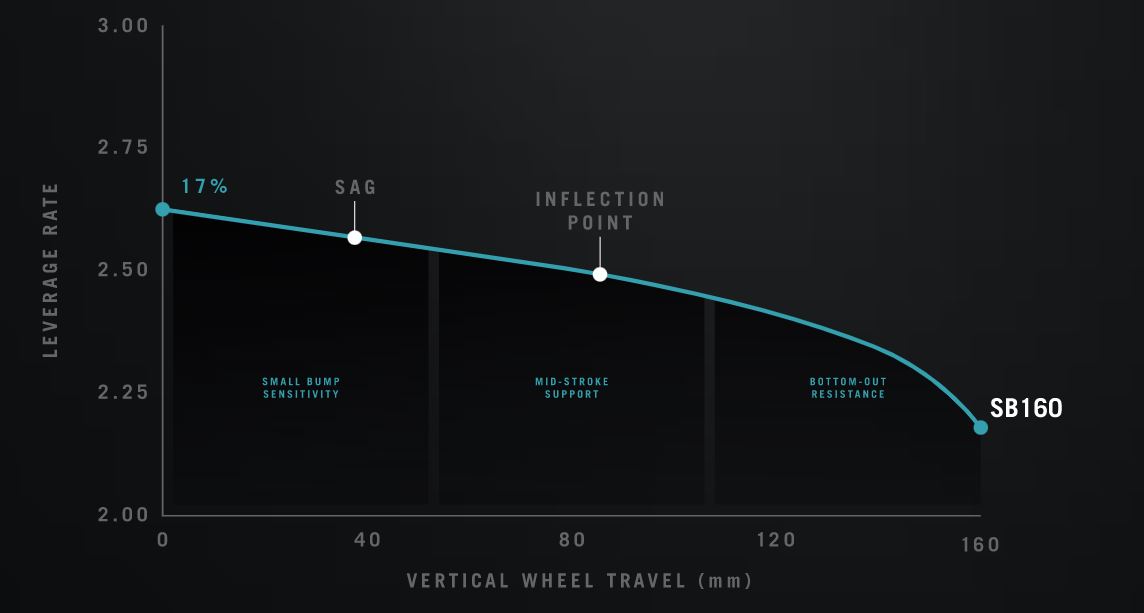

We’d wondered if the wild six-bar linkage from Yeti’s SB160E e-bike would make it over to their conventional mountain bikes, but if that’s in the cards at all, it seems that it’s going to have to wait another generation. The overall layout of the SB160’s suspension is essentially the same as the outgoing SB150’s, with a horizontally-mounted shock driven by a short shock extender, and Yeti’s signature “Switch Infinity” slider taking the place of the lower link in what is still fundamentally a four-bar system. The SB160 gets 17% total progression out of its linkage, going from about 2.6:1 to 2.25:1; the curve is nearly straight in the first two-thirds or so of the travel, before becoming more sharply progressive in the last portion. Yeti says that both air and coil shocks are compatible but only offers air ones on their complete builds.

While the SB160 doesn’t look all that different from the SB150, Yeti’s found a lot more to change than just adding 10 mm of travel. The cable routing is still internal, but bolt-on covers clamp the cables at the exit points to better keep them in place, preventing rattling and rubbing. The bottom bracket shell is now threaded, in place of the PF92 press-fit one on the SB150 (we’ve seen a bunch of manufacturers reversing course back to threaded bottom brackets of late, and that move is a welcome one). The SB160 still has a bit of a hump in the downtube, just forward of the bottom bracket, but it’s been smoothed out for better clearance (and cleaner aesthetics). The downtube still has a big rubber guard on it, should you manage to smash the smoothed-out hump into something, and the chainstay and seatstay guards have been beefed up to better quiet chain slap. The SB160 also gets a SRAM UDH derailleur hanger, and there’s still room for a water bottle inside the front triangle on the full size range. A full set of ISCG-05 chainguide tabs are featured as well.

In addition to those refinements, Yeti has updated their pivot hardware and bearing layout so that all of the pivot bearings (standard sizes throughout) are pressed into the aluminum linkage parts, rather than the carbon fiber frame components. That both reduces the likelihood of a catastrophic mishap in replacing a bearing, and lowers the cost of fixing one should something go wrong. We’ve also seen carbon fiber bearing seats become sloppy and develop play on some bikes that feature them, so this seems like a positive development all around. The pivot axles also use a floating design (similar to fork through-axles from Fox, Ohlins, and others) to compensate for any variations in bearing spacing due to manufacturing tolerances and assembly clearances, which Yeti says should help improve bearing life.

As per usual for Yeti, the SB160 is available in carbon fiber only, with two different layup options. The more basic “Carbon-series” frames use a less expensive layup that adds about 225 g to the frame weight over the top-tier “Turq” frames, but Yeti claims that the two are comparable in terms of strength and stiffness. Yeti also makes a point of emphasizing that they’ve carefully varied the carbon layup of each frame size to tailor the strength and stiffness for the sizes of riders that they expect to be on the respective frame sizes.

The SB160 is designed around a 170mm-travel fork, but condones going as tall as 190 mm if you want to raise the front end and slacken things out; unfortunately, they don’t condone using an angle-adjusting headset in the IS 41/52 mm headtube. The rear brake mount is designed for a 180 mm rotor but can be adapted up to 203 mm, and there’s clearance for up to a 2.6’’ tire and a 34t round (or 32t oval) chainring. So long as you don’t violate those various strictures, Yeti offers a lifetime warranty on the SB160 frame for the original owner.

Fit & Geometry

Yeti offers the SB160 in five sizes, labeled Small through XXL, which they say cover riders from 5’1’’ to 6’11’’ (155 to 210 cm). They’re all dedicated 29ers with fixed geometry, but Yeti has made the leap to size-specific chainstay lengths to make for more consistent handling and weight distribution across the size range. Yeti doesn’t recommend running the SB160 as a mullet, since doing so will dramatically lower the bottom bracket and slacken the headtube and seat tube, but also say there’s no real reason that you can’t do it if you really want to.

The Builds

Yeti offers the SB160 as a frame with Fox Float X2 Factory shock for an eye-watering $5,000, or in one of six complete builds, starting at $6,700. The frame-only option and “T” builds get the lighter Turq frame, while the two less-expensive “C” builds sub in the more basic Carbon-series one. One of the more noteworthy details is Yeti’s decision to spec 220 mm front rotors across the range — a move we’re fully in favor of for this sort of bike; the omission of a “T2” build is also conspicuous, and we wonder if there’s going to be another option added there (likely with a Shimano drivetrain, if we’re taking bets) at some point.

- Drivetrain: Shimano SLX

- Brakes: Shimano SLX 4-piston w/ 220 mm front / 203 mm rear rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Performance

- Shock: Fox Float X Performance

- Wheels: DT Swiss E1900

- Dropper Post: OneUp (S: 150 mm; M: 180 mm; L–XXL: 210 mm)

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX

- Brakes: SRAM Code R w/ 220 mm front / 200 mm rear rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Performance

- Shock: Fox Float X Performance

- Wheels: DT Swiss E1900

- Dropper Post: OneUp (S: 150 mm; M: 180 mm; L–XXL: 210 mm)

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX w/ X01 rear derailleur

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 220 mm front / 200 mm rear rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Factory

- Shock: Fox Float X2 Factory

- Wheels: DT Swiss EX1700

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer (S: 150 mm; M: 175 mm; L–XXL: 200 mm)

- Drivetrain: SRAM X01 Eagle AXS w/ XX1 AXS rear derailleur

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 220 mm front / 200 mm rear rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Factory

- Shock: Fox Float X2 Factory

- Wheels: DT Swiss EX1700

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer (S: 150 mm; M: 175 mm; L–XXL: 200 mm)

- Drivetrain: SRAM X0 Transmission

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 220 mm front / 200 mm rear rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Factory

- Shock: Fox Float X2 Factory

- Wheels: DT Swiss EX1700

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer (S: 150 mm; M: 175 mm; L–XXL: 200 mm)

- Drivetrain: SRAM XX1 Eagle AXS

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 220 mm front / 200 mm rear rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Factory

- Shock: Fox Float X2 Factory

- Wheels: DT Swiss EX1700

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer Factory (S: 150 mm; M: 175 mm; L–XXL: 200 mm)

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) How does the SB160 stack up against a bunch of our favorite race-oriented Enduro bikes, such as the Pivot Firebird, Privateer 161, Orbea Rallon, and others?

(2) And how does the somewhat higher-than-average bottom bracket of the SB160 feel on trail? We had similar questions about the Pivot Firebird (which has notably similar geometry to the SB160 in most respects) and found its bottom bracket height to contribute significantly to the overall character of the bike, so will that be true here as well?

FULL REVIEW

While I review a broad spectrum of bikes, I’m particularly fond of aggressive Enduro ones, and the Yeti SB160 was one of the bikes that I was most looking forward to spending time on this year. And having now spent a lot of time on Yeti’s latest Enduro race bike, it’s become one of my favorite takes on the genre. But while the SB160 is excellent at what it does, it’s not a bike that’s going to be an ideal fit for everyone. So what does the SB160 do so well, and who is it going to work best for (and who would be better off elsewhere)? Let’s get right into it.

Fit & Sizing

Yeti’s suggested sizing for the SB160 puts me (6’ / 183 cm tall) very near the middle of the sizing band of the Large frame, just outside the overlapping regions for both the Medium and XL sizes, and at no point was I tempted to deviate from the Large. Most of the fit numbers — 485 mm reach and a 624 mm effective top tube, principally — are right around my typical sweet spot for this sort of bike, and the SB160 proved to be no exception.

The stack height on the SB160 is a bit on the lower side of average (624 mm on our Large review bike), and I did wind up with a sizeable stack of spacers underneath the stem to get the front end up where I wanted (though I still had a little room to go higher on the amply-long stock steerer tube, and didn’t need to swap in a higher-rise bar or anything like that. And as we’ll get into more below, the SB160 does reward a setup with a not-super-high front end to keep weight over the front wheel, so the more moderate stack height does make a certain amount of sense — not to mention that it is, of course, easier to swap in a higher-rise bar or stem if needed, but at some point your options for going lower become limited.

On that note, after a handful of rides, I did swap in a 40mm-long stem from the stock 50 mm one. I did so for handling reasons rather than fit ones (as is usually my personal preference on most Trail and Enduro bikes, for the more direct steering feel through the bars). I also trimmed the bars down to 790 mm (again, standard for me) and quickly got comfortable from there.

Climbing

The SB160 is one of the better climbing ~160mm-travel Enduro bikes I’ve been on recently, especially for my local terrain, which involves a lot of extended fire road grinds and a fair number of smooth to moderately-technical trails, but only a smattering of really chunky, tricky ones. The SB160’s pedaling efficiency is a notch above average for this sort of bike — not by a huge margin, but some — and while it doesn’t feel like the absolute most plush or planted bike in terms of its suspension performance under power, that’s a tradeoff that I’m very happy to make for this class of bike, and I quite like the balance that the SB160 strikes.

If you’re looking for an Enduro bike that really emphasizes rear wheel traction under power, the SB160 wouldn’t be my first choice. That’s not to say that it feels lacking in that department, but more just that it’s clearly putting pedaling efficiency as a higher priority — which, again, is a tradeoff I’m personally quite happy with. In addition to being clearly welcome on the sorts of fire road grinds that I spend a lot of time on, I think the more supportive suspension of the SB160 can be beneficial on ledge-ier, more technical climbs, too.

As is generally the case with longer Enduro bikes, the SB160 takes more effort to loft over those sorts of obstacles on the way up than more compact (usually shorter-travel) bikes tend to. But the SB160’s relatively firm, supportive suspension helps keep the rear end from squatting down under the sorts of weight transfers that are needed for those moves, helping avoid the sensation of getting hung up on the rear wheel once you’ve lofted the front onto something. Of course, technical climbing isn’t really the SB160’s forte, exactly — nor is it for any of its realistic competitors, as compared to any number of more all-rounder Trail bikes. But the SB160 fares better than a lot of long-travel Enduro bikes, particularly for relatively skilled riders who are willing to give up a little traction under power in exchange for more composure and more manageable handling in those sorts of low-speed, tight moves.

I also got along well with the SB160’s pedaling position over a wide range of climbing scenarios. The seat tube is steep enough to keep the rider’s weight forward on steeper climbs without taking a ton of care to keep the front wheel weighted without being so extreme as to feel awkward when pedaling on flat ground, and the cockpit feels like a nice middle-of-the-road length for a Large frame — neither notably stretched out nor cramped. All told, the SB160’s seated fit just feels nice and normal for a modern Enduro bike.

Descending

Yeti describes the SB160 as having been designed to be an Enduro race bike first and foremost, and its on-trail character feels very much in keeping with that goal. It’s quite stable and composed at speed without being so long and ponderous that it feels like a total handful in the odd tight, janky spot, and it’s quite sharp-handling and precise-feeling once it’s up to a little speed (if ridden confidently and aggressively). It’s composed and planted on steep, rough trails without being a ton of work to muscle around in tighter sections, and it feels precise handling and is easy to pick up and boost over holes and sections of chatter without needing to set up the suspension particularly stiff to get that pop.

But despite being notably nimble at speed for how composed and stable it is, SB160 isn’t a particularly easygoing bike that’s all that interested in being ridden lackadaisically and slowly — the “at speed” part of that statement is important. The SB160 works best being ridden with a more forward, aggressive stance where you’ve got a good bit of weight over the front wheel. Its sweet spot can start to feel narrow if you’re riding tentatively and not pushing the SB160 harder; get on it and over the front end, pick up a little speed, and the SB160 really comes to life.

From a more centered position, the front end starts to feel vague, and the excellent sharp handling that the SB160 displays when being ridden as it prefers starts to fade away. It’s extremely intuitive when being ridden aggressively and has the composure to really go hard on steeper, rougher sections of trail but can start to feel less forgiving of mistakes and a bit of a handful when you let off the gas and stop piloting it as confidently.

Most of the time, I didn’t have much trouble adapting to the SB160’s preferred style, and apart from an initial period of bar height fiddling, I found the SB160’s handling to be quite intuitive, with the bike readily communicating its preference for getting forward and staying over the front end. (I briefly swapped in a higher-rise bar as an experiment, but found that it just made the bike’s sweet spot smaller and made it hard to get over the front end appropriately.) The only time that the game-on nature of the SB160 truly felt like a handful was when riding some very steep rock slab moves on trails I didn’t know up in Squamish. It didn’t feel like the most confidence-inspiring bike once I started to properly scare myself and ride a little more tentatively; the rest of the time it would just remind me that I couldn’t ride too lazily, but was plenty manageable in that.

For an Enduro race bike that’s meant to be pushed hard by a skilled rider, that all makes a ton of sense. The SB160’s suspension performance and overall ride quality also feel well-suited to its intentions. The SB160 isn’t an especially plush and cushy bike, but its suspension feels supportive and composed without being wildly stiff, and the frame’s stiffness feels like a nice middle ground for my preferences — neither brutally stiff and uncompliant nor notably flexy and imprecise. In sum, the SB160 is just a very well-sorted bike with a clear, singular goal in mind: go fast.

The Build

While it’s not exactly the best bang-for-buck out there in terms of parts spec, I really like a lot of the decisions Yeti made in building out the SB160. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve complained about big Enduro bikes coming with too-short dropper posts at this point, so the 200mm-travel Fox Transfer on our size Large SB160 T1 review bike is welcome (though this particular Transfer got sticky and stopped returning smoothly after very little use — something we’ve seen on a handful of them recently). The 220 mm front rotor (and 200 mm rear one) are nice to have on this sort of bike, and I’m glad to see the beefier DT Swiss EX1700 wheels on a 160mm-travel Enduro bike, in place of the lighter-duty XM1700s that often get spec’d.

The only parts I felt the need to swap out were the tires — longtime readers will be unsurprised to hear that I’d rather have beefier casings than the stock Maxxis Exo+ ones for this class of bike, and I subbed in a couple of different sets of heavier-duty ones over the course of the testing. Most notably, this included Continental Kryptotal DHs and a Maxxis Assegai / Minion DHR II combo, with DoubleDown casings and MaxxGrip rubber up front. But overall, Yeti has done a great job of putting together a sensible parts spec with appropriately beefy parts for this sort of big Enduro bike. Slipping a SRAM GX cassette onto what’s mostly an X01 build (that retails for $8,500) is a little underwhelming, but doesn’t make much of a difference when it comes to on-trail performance at the end of the day, and it is worth noting that Yeti has quietly lowered prices a little bit since launch last year — the T1 build that we tested, for example, originally had a $9,100 MSRP.

Yeti’s Switch Infinity slider system has historically had a bit of a reputation for needing frequent service, especially in wetter climates, but Yeti has also made some refinements to the design and materials on their newer Turq-series frames in an effort to address those issues. My testing of the SB160 took place over the tail end of the wetter months here in Western Washington and into what has, so far, been a pretty dry early summer. So while I wasn’t able to subject the SB160 to a full winter of abuse, it also didn’t give me too much trouble.

Yeti recommends a 40-hour service interval for the Switch Infinity sliders, with the basic service just requiring purging the old grease from the system by way of the two grease ports on the side of the slider mechanism and then wiping off the excess. Unfortunately, only the forward slider’s grease port is accessible with the frame fully assembled, so doing the service requires undoing the main pivot and lifting the swingarm out of the way. It’s not too hard but takes a little time (maybe 20–30 minutes, once you’ve got the hang of it) and effort. I did a couple of services over the course of my time with the SB160. After the first, during the wetter part of the year, the grease that came out was quite contaminated and dirty. It hadn’t yet gotten to the point of causing a problem, but folks in wetter climates should be prepared to give the slider some love fairly regularly.

Comparisons

SB150

It’s been a while since I rode the SB150, the bike that the SB160 supplanted in Yeti’s lineup, and I never got more than a couple of rides on it, but my general impressions are that the two share a good bit of DNA, with the SB160 largely feeling like a slightly longer-travel, more stable take on an overall similar bike. An while the SB160 still favors a relatively forward, aggressive stance with a bunch of weight over the front wheel, I think it’s dialed that sensation back a bit as compared to the SB150. Given the new size-specific chainstays on the SB160, I’d expect that aspect to be more true on the larger sizes and less so on the smaller ones, but I’m speculating there — I can only speak to the Large size that I rode for both.

The SB160 and Firebird remind me of each other quite a bit, though there are a few key differences between the two. They’re both especially race-focused Enduro bikes that want to go fast and be pushed hard, and they both display a notably excellent combination of good stability + still sharp handling when being ridden quickly and aggressively. That said, the SB160 is slightly more stable at speed and not quite as quick handling at more moderate speeds, especially in terms of how “nimbly” the Firebird initiates leaned corners (it’s hard to describe succinctly; check out our full review of the Firebird for more on that).

The SB160 also pedals more efficiently than the Firebird but isn’t quite as supple in terms of its suspension performance under power. Even when not on the pedals, the Firebird feels a little more plush but a touch less lively than the SB160. And finally, the Firebird is also more accommodating of a more upright stance on the bike with the bars higher and less aggressive weighting of the front end; the SB160 works best when ridden from a more forward stance. Overall, the Firebird is a bit less game-on and a little more easygoing than the SB160; if you like the idea of the SB160 but want something that’s dialed back just a notch, the Firebird would be high on our list of recommendations.

In some ways, the 161 and the SB160 have a good bit in common. They’re both particularly game-on Enduro race bikes that successfully blend solid high-speed stability with impressively sharp handling for how composed and stable they are, but aren’t very interested in taking things easy or being ridden less aggressively. Their handling is largely similar, though the 161 is a little more stable at speed and the SB160 a touch quicker to tip into mid-speed corners — I think their sizeable difference in bottom bracket height has a lot to do with it. (The 161 is a lot lower than the SB160.)

But, of course, there are massive differences in their design philosophies in other ways. The 161 is made from aluminum and is meant to be simple, reliable, and affordable; the SB160 is unabashedly high-end and expensive, with a lighter carbon frame, more polished hardware and other such details, and more refined frame flex and ride quality in contrast to the very stiff 161 frame. The 161 is frankly the clearly better option for folks looking to go fast on a budget, but the SB160 does feel like the more refined frame in a lot of ways and does have substantially better small-bump sensitivity and traction under power.

The Rallon and SB160 also have some similarities, but the Rallon is a notch less stable at speed than the SB160, correspondingly quicker handling at lower speeds, and pedals more efficiently. The SB160 is more planted and composed in terms of its suspension performance, whereas the Rallon is more lively and energetic-feeling. None of those differences are massive, and they’re still worth cross-shopping against each other. The SB160 is just a little more bike overall, and the Rallon is a touch more versatile as an all-rounder Trail bike.

The Megatower is quite a bit more plush and planted than the SB160 in terms of its suspension performance, but less nimble in tighter spots, less lively, and less precise handling. The SB160 is overall a more game-on, committed race bike, whereas the Megatower is more forgiving of being ridden less aggressively and taking things easier, while still being able to be pushed quite hard. The SB160 also pedals quite a bit more efficiently, but doesn’t offer as much traction under power on loose surfaces as the Megatower.

The sizing breaks between the two are also substantially different — I personally felt on the brink between the Large (that I tested) and XL sizes on the Megatower, but squarely in the Large camp on the SB160.

The G1 is quite a bit longer and slacker than the SB160, and as you’d expect, feels more stable at speed, less nimble in tighter spots, and generally more composed on very steep, rough descents but more of a handful when things get really tight and weird. Pedaling efficiency between the two is actually pretty close, but the SB160 has a slight edge there, and is more manageable in tight, technical climbing situations. The G1’s suspension is more supple off the top and offers a bit more grip but the SB160 is easier to pick up and boost over holes and the like; the G1 is more planted feeling.

The Capra stands out for being an especially easygoing take on a long-travel Enduro bike that can still be pushed quite hard when called upon, but is notably more forgiving of being ridden less aggressively than the SB160. The Capra has a bigger sweet spot in terms of its preferred body positioning, especially in that it’s more accommodating of being ridden more centered and upright. The Capra’s suspension is also much more plush and cushy; the SB160 is more lively in terms of its suspension performance, much sharper handling / more precise feeling, and pedals more efficiently.

The Capra is also offered in seperate 29er and MX versions; we’ve only tested the former, and those comparisons above are all referring to the Capra 29. Given the smaller rear wheel and much shorter chainstays on the Capra MX, we’d expect it to be quicker handling but less stable and probably prefer a more forward stance than the Capra 29, but those suspensions have yet to be confirmed.

The VHP16 is another take on a notably playful, easygoing Enduro bike. It’s not all that similar to the Capra in terms of the particulars of how it goes about that, but it’s still very, very different from the SB160. The VHP16 is much more nimble and quick handling; its suspension is more plush and cushy, especially at lower speeds when you aren’t hitting things as hard; and it’s easier to throw around in the air and generally ride more playfully. The VHP16 also has much more traction under power than the SB160, but actually pedals just about as efficiently, too. The SB160 is more stable at speed, more composed when you start really going fast and pushing it hard, and generally feels like a more race-focused bike, whereas the VHP16 is the more versatile all-rounder.

Super different. The SB160 is a fairly stable, composed bike that’s also relatively nimble for how stable it is; the Range is supremely composed and unflappable going extremely fast on steep, rough trails but is decidedly not nimble or sharp handling. They’re both aggressive, game-on bikes, but go about that very, very differently. The more you want a pedalable DH bike, the more the Range makes sense; the SB160 pedals far more efficiently and doesn’t need as much pitch or speed to come alive (though, again, it’s still not a bike that really wants to take it easy).

Also very different. The Dreadnought is more stable at speed and better at just plowing through whatever’s in front of it (though not quite to the same degree as the Range); the SB160 is more nimble, much more intuitive in terms of its handling (especially at medium speeds), and wants to be ridden from a more forward stance (whereas the Dreadnought specifically favors a more centered, upright body position). The Dreadnought is also more planted / glued to the ground in terms of its suspension performance; the SB160 is feels more lively.

Who’s It For?

Yeti talks a lot about the SB160 being developed to be an Enduro race bike first and foremost, and it indeed feels like a bike for folks who either actually are racing regularly, or who just want a bike that they’ll consistently push hard and ride fast on burly trails. It’s not the most easygoing or versatile ~160mm-travel Enduro bike out there, but it’s impressively sharp handling and nimble when needed, relative to how stable and composed it can be at speed. That’s a great recipe for the sorts of riders who have the skills and inclination to ride the SB160 with the kind of aggressive touch that’s needed to get the most out of it.

Bottom Line

Modern “Enduro” bikes cover a pretty wide spectrum, from more playful, Freeride-oriented options, to long-legged Trail bikes, easygoing all-rounders, and committed, game-on race bikes. The SB160 is squarely in the latter camp, but it’s an excellent example of the genre. You should look elsewhere if you’re after a super versatile long-travel all-rounder, or an especially forgiving, easygoing bike that’ll readily make up for sloppy, tentative riding. On the other hand, skilled, aggressive riders who want a bike that they’ll use to go fast on a mix of burly descents and awkward jank are likely to find the SB160 an especially compelling option. It’s an unapologetically focused bike, but for the right rider, it’s a great one.

I need to befriend a 6’3″ dentist so I can convince him to sell me his used SB160 after he’s done with it.

Same. Im 6’3” and selling my Firebird so looking for a 160.

Bikes are too expensive at $4000. A dirtbike is such a better deal. I don’t see the cost/value in these bikes and it seems to me they need to figure out how to lower costs like any other business model.

Would you expect the 160-E to share these characteristics, or is it a different beast?

Loved the review and comparison to the other models. Thank you!

A specific comparison between the SB160 and the Megatower would be interesting, specifically which bike you’d prefer in certain use cases, Squamish slabs, A Line laps, or single trails like Dark Crystal in Whistler.

Great review. I’ve recently bought one, and as a more novice rider it is true that it is above my pay grade to really get out of it what is possible. I had a Spec Enduro, and that was more of a plow machine than this, so provided me with a significantly larger window for error and feedback. Nonetheless, it feels extremely capable and when I can dial that in, its very wildly fun. Wasn’t mentioned here, but under braking, they way the geometry is maintained is very impressive.