Öhlins TTX22

Size Tested: 8.5 x 2.5”

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- Shock body w/ hardware: 455 g

- 343 lb spring: 278 g

- 365 lb spring: 304 g

Total:

- 733 g with 343 lb spring

- 759 g with 365 lb spring

MSRP:

- Shock body, without spring: $755

- Lightweight steel spring: $95

Bolted to: Nicolai G16

Reviewer: 6”, 165 lbs (183 cm, 75 kg)

Test Location: Washington

Test Duration: ~3 months

- 7.5 x 2’’

- 7.875 x 2’’

- 7.875 x 2.25’’

- 8.5 x 2.5’’ (tested)

- 8.75 x 2.75’’

- 9.5 x 3’’

- 10.5 x 3.5’’

- 210 x 50 mm

- 210 x 55 mm

- 230 x 60 mm

- 230 x 65 mm

- 250 x 70 mm

- 250 x 75 mm

- 165 x 45 mm

- 185 x 50 mm

- 185 x 55 mm

- 205 x 60 mm

- 205 x 65 mm

- 225 x 70 mm

- 225 x 75 mm

[Note: For metric shocks, the above configurations are available stock. The shorter stroke of a given eye-to-eye (e.g. 230 x 60 mm vs 230 x 65 mm) is reduced with a spacer. 2.5 and 7.5 mm spacers are also available, to achieve in-between sizes, such as 230 x 62.5 mm and 230 x 57.5 mm.]

Intro

We recently reviewed Öhlins’ RXF36 m.2 Trail / Enduro fork and came away impressed. Next up is the brand’s TTX22 rear shock, a coil-sprung unit meant for use on Trail through Downhill bikes. There are lots of shocks to choose from them these days — and many are quite good — so how does the TTX22 perform, and how does it compare to the competition (including the excellent EXT Storia V3)? I’ve spent the last few months with the TTX22 to find out.

Design

The TTX22 uses a twin-tube damper design, which has been a hallmark of Öhlins’ mountain bike offerings over the years. Indeed, their first foray into mountain bike suspension was to collaborate with Cane Creek on the original Cane Creek Double Barrel, one of the first mass-market, twin-tube shocks for mountain bikes. As you’d expect from a high-end shock in this category, the TTX22 features adjustable high- and low-speed compression, and a single rebound adjuster.

Sizes of the TTX22 meant for Trail / Enduro bike duty get a climb mode in lieu of the third high-speed compression position. Settings one and two are the options for normal high-speed compression damping, and the third activates the climb mode. On longer lengths designed more for DH use, the third position is instead an additional high-speed compression setting.

This does mean that the overall tunability on the high-speed compression adjuster is somewhat more limited than it is on many other shocks. The 8.5’’ x 2.5’’ size we’ve tested has the climb mode in the third position, and while there’s a substantial difference between the two “normal” settings, there’s less ability to fine-tune the high-speed compression setting than on shocks like the EXT Storia, Fox Float X2, and Fox DHX2.

The TTX22 damper uses a bladder for oil-volume compensation, instead of the more common internal floating piston (IFP) arrangement. Öhlins argues that a bladder design can reduce friction, due to not requiring a sliding seal, as with an IFP. Similar to what EXT claims with their Storia rear shock, Öhlins says that the TTX22 damper is designed to induce turbulent flow at very low shaft speeds, with the goal of limiting the impact of oil temperature on damping. Our EXT Storia review goes into more detail on the differences between laminar and turbulent flow, and their relevance to mountain bike damper design. If you want to go a bit deeper on the subject, check out the “Other Design Elements” section of that review.

Unlike some other twin-tube shocks, including the Cane Creek Double Barrel and pre-2021 Fox Float X2 and DHX2, the TTX22 uses a check valve to prevent oil from backflowing through the outer tube during rebound; in short, this makes the TTX22 behave like a twin-tube shock on compression, and a monotube design on rebound. Twin-tube dampers have very real advantages when it comes to preventing cavitation on the compression stroke, and reducing the spring force provided by the gas charge behind the IFP / bladder, but also tend to limit designers to a digressive rebound-damping curve (i.e., lots of damping at low shaft speeds, and less at higher ones) so this arrangement is a clever way for Öhlins to have their cake and eat it too, so to speak.

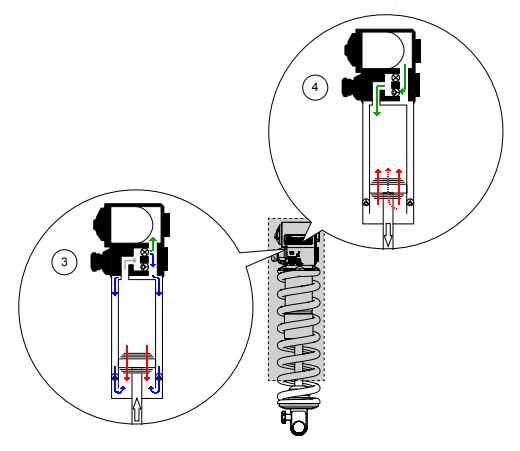

The oil-flow paths for the TTX22 are shown below. The image labeled “3” is the compression stroke, and “4” shows the shock under rebound. Under compression, oil flows both through the main piston (red) and around the outer tube to fill in behind the main piston. The oil displaced by the damper shaft flows into the reservoir and displaces the diaphragm (green). Under rebound, the check valve closes flow through the outer tube, and oil flow is limited to the return of the oil from the reservoir (green) and back through the main piston (red). The solid red flow lines indicate flow through the piston itself, while the dashed red line shows flow through the rebound adjustment needle.

Another interesting claim that Öhlins makes about the TTX22 damper is that they’ve used a mix of aluminum and steel parts in the rebound-adjuster assembly, to take advantage of the differing rates of thermal expansion of the two materials to compensate for variations in rebound damping due to heat in the damper. The idea here is that the disparate thermal expansion ratios of the two materials vary the size of the rebound-needle opening based on the internal temperature of the shock, and thereby compensate for damping changes that result from the oil viscosity changing with temperature.

Öhlins maintains a large database of bike kinematics and offers a wide variety of stock tunes to suit different bikes. Depending on the particulars of the setup, Öhlins will vary the damper tune and also offer multiple bottom-out bumper sizes, to suit frames with varying amounts of progression and different rider preferences. The list of bikes for which Öhlins has a standard tune developed can be found on their site. If you’re interested in running a TTX22 on a bike not currently in the database, you can discuss a setup with Öhlins directly, or one of their various service centers around the world.

The TTX22 is offered with both standard DU bushing hardware, and spherical bearing mounting options. For mounting on my Nicolai G16, Öhlins recommended a DU bushing at the forward shock mount (which sees very little rotation) and a spherical bearing at the rear. The spherical bearing is meant to both rotate more freely than a bushing, and allow for some angular misalignment between the two ends of the shock, due to frame flex and/or manufacturing tolerances, with less friction and binding than a pair of bushings.

Öhlins also makes lightweight steel springs to go with the TTX22, in 4 Nm (23 lb/in) increments. They’re sold separately from the shock body, and retail for $95 each. At a measured weight of 278 g for a 343 lb/in, 2.5’’-stroke spring, their weight is roughly in line with other lightweight steel springs from the likes of EXT and Fox.

On the Trail

I’ve tried a lot of different shocks on my Nicolai G16 over the years, making it a good test bike for me to compare and contrast new ones. I’ve found ~350 lb/in springs to be the right range for me on the bike, and Öhlins sent both 343 and 365 lb/in options with the shock.

The initial setup for the TTX22 was straightforward. The fact that the high-speed compression adjuster effectively only has two positions (discounting the third, climb-mode setting) does limit fine-tune-ability some, but it also means that there’s a bit less to think about and dial in when it comes to setup. It also means that it’s easier to toggle between the two and achieve different setups based on a given trail or set of conditions than it might be on a shock with more granularity to the adjuster (in this respect, it’s somewhat similar to the special RockShox Super Deluxe on the latest Trek Slash, though that shocks’s 3-position adjuster is for low-speed compression). For the most part, I found myself preferring the TTX22’s lighter HSC setting for steeper, more natural trails, and would bump up to the firmer one for higher-speed, more bike-park-y ones. As with the RXF36 fork, the high-speed compression tune supplied with the TTX22 is somewhat on the firm side, but for my preferences, Öhlins nailed the tune, making both of the high-speed compression settings very usable.

Compared to the EXT Storia that I reviewed last year, the TTX22 isn’t quite as completely frictionless and smooth off the top, and offers a slightly more lively, poppy ride. Of course, the Storia is a custom-tuned, made-to-order shock, and I specifically asked for — and got — a tune that favored very planted, grippy setups. The TTX22, as configured here, feels a bit more balanced in its setup. It’s not quite as ground-hugging-ly planted as the Storia, but also feels more lively.

Mostly, though, the TTX22 is just a very high-performing shock, with a relatively straightforward setup. I’ve toggled between the two high-speed compression settings as mentioned above and experimented with a range of low-speed compression settings. While the adjusters are effective, I haven’t arrived at a combination of settings that felt far out of whack, either — the TTX22 has just felt composed and predictable across a big range of settings.

That consistency and predictability is really the throughline of my time on the TTX22 — it just works well, hasn’t ever felt like it was doing anything strange or unexpected, and has remained consistent in its performance, even under some long, high-speed shuttles that put a lot of heat into the shock. There’s not necessarily one specific area where it’s so obviously superior to the competition as to dramatically stand out, but it just works well everywhere, and feels unflappable — it simply hasn’t done anything unexpected, or felt harsh, or lacked rebound control, or anything else. It’s the kind of performance that just disappears underneath you, and lets you get on with your ride without drawing attention to the shock.

It can be hard to realize just how good that is, in its own way, until you put a lesser shock back on, and realize just how many rough edges the TTX22 was smoothing over without you realizing. In particular, going back to a 2020 Fox Float X2 — i.e., the prior-generation shock, not the most recent version — exposed how lacking the rebound control of that shock can be, particularly in repeated high-speed hits.

The TTX22’s climb mode is reasonably effective, but doesn’t firm things up quite as much as the Lok lever on the Storia. Since the TTX22 is effectively preloading the compression valve in the bridge, instead of activating an entirely separate circuit, there’s less ability to tune the behavior of the climb mode independently from the rest of the shock, but I doubt that most people will find this to be a significant limitation. I haven’t yet ridden the updated 2021 Fox DHX2, but it shares its damper design with the Float X2, and the climb mode on the TTX22 is notably firmer than that on several different versions of the Float X2 that I’ve spent time on.

The TTX22 also lacks the hydraulic bottom-out circuit featured in the Storia, but I haven’t found it to be wanting for bottom-out control. The TTX22’s bumper is larger than on many shocks and has done a good job of muting out any hard bottom-out events, though it’s worth noting that the G16 I’ve been testing the TTX22 on is itself quite progressive, and therefore doesn’t require a ton of help from the rear shock to manage the end of the stroke.

I’ve also had no issues to report with the TTX22 whatsoever. It’s been quiet and performed reliably and without complaint throughout my time on it.

Öhlins has made an impressively well-refined product in the TTX22, and one that’s a great option for riders looking to eke some more downhill performance out of their Enduro or Downhill bikes.

Bottom Line

The Öhlins TTX22 is a very high performing shock with a straightforward setup, and is a particularly good option for riders who are willing to pay for high levels of overall performance, but are less interested in wading into the world of custom tuning or a shock that requires a more precise and involved setup to get feeling great. At $755 for just the shock body, the TTX22 is on the expensive end of the spectrum, but isn’t out of line with its competitors, either — and in fact is nearly identical in price to the EXT Storia, once you factor in two lightweight springs. All in all, the TTX22 is a great shock that has performed consistently and predictably in my time on it, and if you’ve got a bike that Öhlins has developed a tune for, you can expect very good performance out of the box, with little fuss.

This review is exactly what I’ve been looking for. Thank you. I have a G16 and am considering the TTX22M as I am certain I want to get a coil shock. I intend to buy a 222×70 shock (with offset bushes) as this is what I prefer in my air shock set up on this bike. I do have a question. Bases on your experience, do you think the absence of the climb mode be problematic on the G16? 222×70 is a DH mode and therefore doesn’t get this. Thanks! Jon.

You’ll get a little more suspension movement, especially on smooth fire road climbs, but I think you’ll be fine. The G16 pedals pretty well for what it is.