EXT Storia Lok V3 Coil Shock

Bolted to: Nicolai G16

Reviewer: 6”, 165 lbs

Test Location: Washington

Test Duration: ~3 months

Size Tested: 8.5 x 2.5”

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- Shock body: 400 g

- 350 lb spring: 266 g

- 375 lb spring: 290 g

- Reducers (22.2 x 8 mm): 13 g

- Total Weight:

- 679 g with 350 lb spring

- 703 g with 375 lb spring

MSRP (includes two lightweight coil springs): $1000 USD / €799

Sizes Available:

- 7.5 x 2”

- 7.875 x 2.25”

- 8.5 x 2.5” (tested)

- 8.75 x 2.75”

- 190 x 45 mm

- 210 x 50 mm

- 210 x 52.5 mm

- 210 x 55 mm

- 230 x 57.5 mm

- 230 x 60 mm

- 230 x 62.5 mm

- 230 x 65 mm

- 250 x 67.5 mm

- 250 x 70 mm

- 250 x 72.5 mm

- 250 x 75 mm

- 165 x 45 mm

- 185 x 50 mm

- 185 x 52.5 mm

- 185 x 55 mm

- 205 x 57.5 mm

- 205 x 60 mm

- 205 x 62.5 mm

- 205 x 65 mm

- 225 x 67.5 mm

- 225 x 70 mm

- 225 x 72.5 mm

- 225 x 75 mm

Intro

EXT (Extreme Racing Shox) is an Italian company with a long history of making suspension for professional motorsports, including F1 and World Rally cars, motorcycles, ATVs, and others. But in recent years, they branched out into the world of mountain bike suspension.

For the past few months, I’ve been testing the latest version of their Storia Lok coil shock, which they target at the Enduro market, and have come away extremely impressed. This is a unique, high-end shock with several interesting features (and on-trail characteristics), so let’s get right into it:

The Design

EXT has only ever offered coil-sprung rear shocks — though their recently released Era Enduro fork uses a rather interesting hybrid coil / air spring layout — and the Storia Lok V3 is their offering aimed at the long-travel Enduro market.

The overall layout is fairly traditional. The Storia is a mono-tube shock, which is the more conventional layout used in most mountain bike rear shocks; the Cane Creek Double Barrel, Ohlins TTX, and Fox DHX2 / Float X2 are the major exceptions, and if you want more info on what I’m talking about, Vorsprung Suspension has an excellent video outlining the differences.

As a mono-tube coil shock, the Storia Lok has a rebound adjuster at the lower shock eyelet, which meters oil flow through the main piston; high- and low-speed compression adjusters on the bridge between the main shock body and the reservoir; a climb switch below the compression adjusters; an external reservoir housing an internal floating piston (IFP) to compensate for oil displacement as the shock cycles; and a coil spring over the outside of the shock body.

While none of those external features are particularly out of the ordinary for a high-end, modern coil shock, internally, things get more interesting.

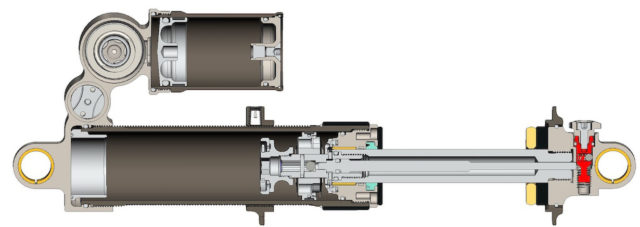

Hydraulic Bottom-Out Circuit

One of the most notable features of the Storia is the addition of a hydraulic bottom-out circuit. The way it works is actually rather simple — as with basically every rear shock on the market, the main piston on the end of the shock shaft passes through the oil that fills the shock body, and a shimmed valve on the piston provides compression damping as the shock compresses. The Storia, however, adds a second, smaller-diameter piston in front of the main one, which can be seen in the cutaway image below. Through most of the shock’s stroke, there’s a gap between this piston and the inside of the shock body, so that oil flows around the piston and its valving doesn’t provide any damping. However, at the end of the stroke, the secondary bottom-out piston enters a smaller-diameter tube at the end of the shock body, sealing around the outside of the secondary piston and bringing its valving into play as well. At this point, oil must flow through both pistons for the shock to continue to compress, which consequently increases the amount of compression damping.

The amount of added compression damping provided by the bottom-out circuit isn’t externally adjustable, but can be tuned when the shock is taken apart for service. EXT’s DH-oriented shock, the Arma, ditches the Storia’s climb switch in favor of an external adjuster for the bottom-out control.

Since the Storia relies predominantly on the hydraulic circuit for bottom-out control, its physical, foam bottom-out bumper is far smaller than on most coil shocks — essentially just a foam washer, about 5 mm thick.

The idea behind Storia’s hydraulic bottom-out damper is that a typical bottom-out bumper is really just an undamped spring, and so when it’s compressed, it subsequently returns the energy put into it in the form of rebound. By contrast, a hydraulic bottom-out damper dissipates that energy as heat, leading to more controlled behavior when the shock bottoms out.

Lok Climb Switch

When activated, the climb switch routes the compression part of the cycle through a separate valve, instead of adding preload to the standard compression damping circuit to firm things up.

Storia’s approach is an increasingly common tactic — for example, Fox changed to this style of climb-switch mechanism on the 2021 DHX2 and Float X2 — since it allows the climb switch to be valved entirely independently of the regular compression circuit. As with the Storia’s bottom-out circuit, the climb-switch circuit isn’t externally adjustable, but can be revalved during a service.

Other Design Elements

EXT makes a point of noting that the Storia uses an uncommonly large, 29mm-diameter main piston and 24mm-diameter base valve in the shock bridge, which allow for greater oil flow at high shaft speeds, and a very low 55 psi charge in the reservoir (125 to 200+ psi is more common) to increase the shock’s sensitivity to smaller inputs.

Speaking of the piston, EXT also says that the valving in the shock is specifically designed to induce turbulent (as opposed to laminar) flow through the damper, with the idea that this reduces the effects of oil viscosity changing with temperature. The entire point of the damper is to dissipate kinetic energy as heat. That heat has to go somewhere, and it inevitably ends up warming the oil within the shock. As the oil gets warmer, its viscosity decreases, causing a reduction in damping provided by the shock; by promoting turbulent (again, as opposed to laminar) flow through the damper, EXT aims to mitigate this behavior. It’s probably an oversimplification to say that the flow through any shock is uniformly turbulent or laminar under any and all circumstances, but the idea that turbulent flow mitigates the dependency on oil viscosity is sound.

[If you’re wondering about the difference between turbulent and laminar flow, picture a fluid (air, oil, water, whatever) flowing through a straight pipe; at lower flow rates, that flow will be orderly, with each molecule going in basically a straight line through the pipe. Streamlines near the sides of the pipe move slower, due to friction against the walls; the closer to the center of the pipe you get, the faster the flow moves. That’s laminar flow. As the flow rate increases, at some point this order breaks down, and chaos ensues, with the flow swirling and churning as it makes its way through the pipe; that’s turbulent flow. This example with a straight pipe is the simplest version to visualize; the geometry of the flow path and a variety of other factors are relevant to the transition from laminar to turbulent flow as well. And, with that tangent into physics class out of the way, I promise I’ll stick to talking bikes for the rest of the review.]

The spring collar on the Storia features a plastic set screw that nestles into one of six grooves machined around the shock body, which is designed to prevent the collar from unthreading, particularly when running light preload. It’s simple and works great, and I’d love to see something similar on other coil shocks.

Ordering Process

All of EXT’s shocks are custom made to order, in Italy, and custom valved for the specific rider and application. EXT has a number of distributors around the world; check their website to find one in your area.

I ordered my shock through Suspension Syndicate, the US distributor, and the process was straightforward, though a bit more involved than buying a standard shock off the shelf. First, you fill out a form online with your height, weight, riding background and preferences, the bike the shock is intended for, and so on. Having done that, Suspension Syndicate will reach out to schedule a short phone call to go over the form responses, and discuss how the shock is to be tuned. With that complete, they’ll send an invoice for the shock, and once that’s paid, they’ll send the order to the EXT factory.

I received the shock about seven weeks after placing the order, but this was in mid-April, when the coronavirus pandemic had much of Northern Italy in full lockdown; Suspension Syndicate says that two to four weeks is more typical. EXT ships all of their shocks with two lightweight steel coil springs, usually with a 25 lb difference between the two, to give riders options to find their ideal spring rate, and perhaps have heavier and lighter options for use on different terrain, with and without a heavy pack, or on a bike with multiple travel settings via a linkage adjustment. If one or both of the initial spring options turns out to be off, Suspension Syndicate will allow you to ship the spring to them for a free exchange in the first few weeks after receiving the shock.

I weigh 170 lb, and ordered the Storia in the shorter 8.5 x 2.5” size for my Nicolai G16 (that bike can work with different-sized shocks), which yields 155 mm of rear travel. EXT sent the shock with 350 and 375 lb springs, which proved to be right on. I’ve mostly preferred the 350 lb option for my relatively steep home trails in Western Washington, but have used the 375 lb a bit on some flatter terrain, where my weight bias is a bit more rearward overall. For reference, I’ve mostly run a 350 lb spring with the Fox RC4 that I use on the bike as well, so the Storia has matched up with that nicely. It is a bit outside of the norm (and a nice touch) for a shock to come with two high-end springs chosen by the manufacturer for the application, with the ability to swap them out if need be.

On the Trail

The first thing that jumps out immediately after installing the Storia is just how freely the shock starts moving with the slightest weight on the saddle. In fact, the shock sags ever so slightly under just the weight of the bike. I don’t think I’ve ever used a shock that was so supple off the very top of the stroke.

The second thing I noticed, unfortunately, was that the rebound felt very, very slow. Even with the rebound adjuster wide open, it was notably slow, especially at lower shaft speeds near the top of the shock stroke. It opened up and sped up some when getting deeper into the stroke, but not enormously so. After a couple of rides, I decided that the initial rebound tune truly was off, and sent the shock back to Suspension Syndicate for a revalve. A couple of weeks later (they performed the service at their location in Salt Lake City — no need to send it back to Italy for service) I had it back.

The revised rebound tune is greatly improved. I’m still running the rebound at or near wide open, depending on which spring rate I’m using and how I’m setting up the shock for the terrain I’m on, but I no longer need it faster, either.

The climb switch (the “Lok” in Storia Lok V3) is effective, significantly firming up the compression damping, but not to the extent that it approaches functioning as a lockout. Since the lever routes the compression cycle of the damping through an entirely separate valve as the open position, it’s a binary switch, unlike some shocks (e.g the older Fox Float X2 and DHX2, before their 2021 redesign) that preload the standard compression valve and therefore offer a range of settings across the sweep of the lever. Of course, with the Storia, there’s a great range of tuning options available from the factory, depending on the needs of the rider and bike it’s intended for. Frankly, my conversation with EXT about my desired setup focused almost entirely on downhill performance, and didn’t cover the climb switch setting much. I’d say I got a nice middle ground between firming up pedaling performance without making the shock so stiff that it begins to lose significant traction. If you’ve got more specific needs, EXT can work with you.

Of course, coil shocks are going to generally suit gravity-oriented riders more than the spandex crowd, and on the way back down, the Storia is impressive.

The most notable trait is just how well the rear of the bike tracks the ground, and how much grip is available. I’ve mostly run my G16 with a Fox Float X2 (the first generation, pre-2021 version) and a Fox RC4 (2015-2016, small-shaft version). And even the RC4, a DH-oriented coil shock, can’t match the Storia in terms of how seamlessly it keeps the bike glued to the ground. The Storia’s compression damping doesn’t feel light by any stretch — it’s a very muted, controlled sort of compliance, as if the shock can be set up with firmer damping than most, but without then feeling overdamped and harsh on sharp, square edged hits and bigger landings.

That’s precisely what I wanted out of the tune, and what I asked EXT for; my background is mostly in riding and racing DH, and that’s still reflected in my riding style. My favorite riding is steep, raw, technical terrain, and I’m much more inclined to try to go fast and look for grip anywhere I can find it than I am to adopt a more playful, poppy, slopestyle-influenced style. The tune EXT delivered on the Storia isn’t dead by any means, but it’s certainly more heavily damped and controlled than it is poppy. That suits me really well, but again, go into the ordering process with a clear picture of what you want from the shock (and realistic expectations about what’s possible — tuning decisions come with tradeoffs, after all) and you’ll be much more likely to get a result you’re happy with.

I’ve put the Storia through quite a few sustained descents of several thousand feet, and while I’ve certainly gotten the body of the shock warm to the touch, the performance has been impressively consistent. It’s not uncommon for shocks (especially smaller / lighter, more Trail-oriented options) to overheat to the point that their damping performance suffers, but I’ve noticed none of that from the Storia. Despite warming up appreciably on a number of occasions, it’s continued to function reliably.

The high-speed compression adjuster is one of the few points of annoyance I have with the Storia: it requires a 12 mm box wrench to turn it. I’m not mad that it requires a tool, but if EXT is going to use a non-standard tool that’s not found on most multitools, it would be nice to see them include a widget for that adjuster, like Fox does with the DHX2 and Float X2, despite those adjusters being common 3 and 6 mm Allen wrenches. I ended up making a tool myself to throw into my pack, but that’s not going to be a realistic option for most people, and I wouldn’t mind having that hour of my life back.

[Update: Suspension Syndicate reached out to say that they recently started making a small tool for the high-speed compression adjuster, and are working on a new version of the tool that also has a flat-blade screwdriver for the shock’s spring retainer set screw.]

The Storia is also a bit louder than some other shocks. Part of that comes down to the fact that there’s just more noise of oil moving through the shock than average, especially on rebound. And the other part is that the bottom-out bumper rattles slightly. The bumper itself is just a foam washer, but it also has a machined plastic washer on top of it to contact the shock body and give the foam a flat surface to press against. The end of the shock body where the foam bumper would otherwise contact is heavily machined and relieved, and the edges of those pockets would likely cut the bumper to pieces without it, but the plastic washer is loose on the shaft and made some noise, which I solved by gluing it to the foam bottom-out bumper. It’s a minor thing, but that’s a small detail I’d like to see better polished. With that sorted, I haven’t found myself noticing the damper noises most of the time on trail, but do occasionally catch a little hint of them. I doubt most people will care or even notice, but bike-noise obsessives should take note.

Bottom Line

If those last two paragraphs sound like I’m quibbling about some really minor annoyances, it’s because that’s all I can find to fault with the performance of the EXT Storia Lok V3 (now that the rebound tune has been squared away.)

It’s a truly excellent shock, particularly for gravity oriented riders who know a bit about how they want a shock to work / feel, and who can clearly communicate those desires.

At $1000, the Storia Lok V3 is undeniably expensive, but it’s worth keeping in mind that two lightweight steel springs are included in that price; for comparison, a Fox DHX2 and two of their SLS springs retails for $929, and a Push ELEVENSIX goes for $1,200.

For riders looking for the utmost downhill performance out of their long-travel Trail and Enduro bikes, the Storia Lok V3 is an outstanding option.

First: Please show us a picture of the on-trail tool you built.

Second: Tell us where you ended up with your compression settings.

My Storia came with a G1 frame (how handy) from Geometron. Even though I like fast rebounds, I had to close the rebound half way with a 450 spring.

Funny.. you guys reviewed both of my suspension products on my bike in the last few days : ext storia v3 and the manitou mezzer (both on a Levo SL)

My experience with the storia has been great! I am running it with a sprindex 550-610lb spring which adds even another element to adjustability. Shock feels composed – the best way I can put it. It’s not as sofa plush as my old bike with an Ohlins ttx22m (though that was at 180mm travel vs 150mm on the SL), but it does better on fast, steep, rough terrain.

I love the HBO given the linear nature of my bike (~21% progressivity as I have it setup now ). Pretty much all of my dh PRs have been set by this bike. Definitely worth looking into if you are the market for a high end shock

EXT Storia V3 vs. Push Elevensix?

Can you provide any comparison between these two shocks?

Did this version of the EXT have the negative coil spring that Geometron specs on their bikes?

It didn’t. The coil negative spring started with the G1. My understating is that there’s not room for it in the imperial sized shock on the G16.

I recently picked up a Storia (mounted to a Canfield Lithium, thanks for the rec!) and am generally stoked on it, but I have definitely noticed the rattle from the plastic washer. You mention gluing it to the foam bumper – any thoughts on the right adhesive to use? Thanks!

I think I used Barge Cement (or maybe Shoe Goo). I figured something that stays flexible and has pretty good adhesion to plastic were going to be the most important criteria.

Good morning great review thank you David. Any plans to review the E Storia? Im looking to put it on a GG Gnarvana and the adjustable HBO looks pretty cool. I wish they had come up with a better solution for the compression adjustment that was either tool free or with a hex bit. One question, what do you run on your personal enduro bike(s)? Is its worth the bucks or like the majority of the DH circuit, the mainstream brands will do just fine. I ride 3-5 times a week, mostly big lines jumps, drops, steeps.