Intro

“All you need is a pair of shoes.”

You’ll hear this aphorism a lot from trail running devotees, and they’re not wrong. There are even those that’ll make the case for dispensing with soles and laces and rubber altogether. After all — and especially relative to other modern-day sports — running is almost primitive, with minimalism threading a throughline through the sport. Compared to more gear-intensive hobbies, the price of admission — a pair of shoes — is paltry, making running a genuinely democratic activity that most can enjoy.

But trail running is only cheap until your body decides to collect on its debt. Injury rates among runners are annually on the wrong side of 50%, with a large portion of that group made up of people new to the sport. Sometimes worse than the ache from plantar fasciitis or shin splints — two overuse injuries so common it seems like they’re contagious — is the financial toll from blindly spending money on questionable treatments and products to cure them. Anyone unlucky enough to have gone through a withdrawal from running knows how persuasive desperation can be.

“Prevention is better than cure.”

Another aphorism you might overhear. Injury does not have to be a rite of passage. Running’s lack of gear should not belie the importance of that gear — your shoes. Knowing how to find and use footwear to support your running style and preferences is an important aspect of the sport. It’ll also go a long way in keeping you healthy and keeping running affordable by avoiding the products that aren’t for you.

But like any activity relying on equipment, the trail running industry can sometimes bloat with confusing jargon. Brands love to come up with their own slick terms for technologies and styles already widely in use, effectively selling you the same thing under a different name. To help translate some of that often confusing technical language — and to complement our in-depth shoe reviews — we’ve put together a glossary of terms that folks new to trail running should be familiar with before going on their first shoe search (and that could help experienced runners find the best shoe for them).

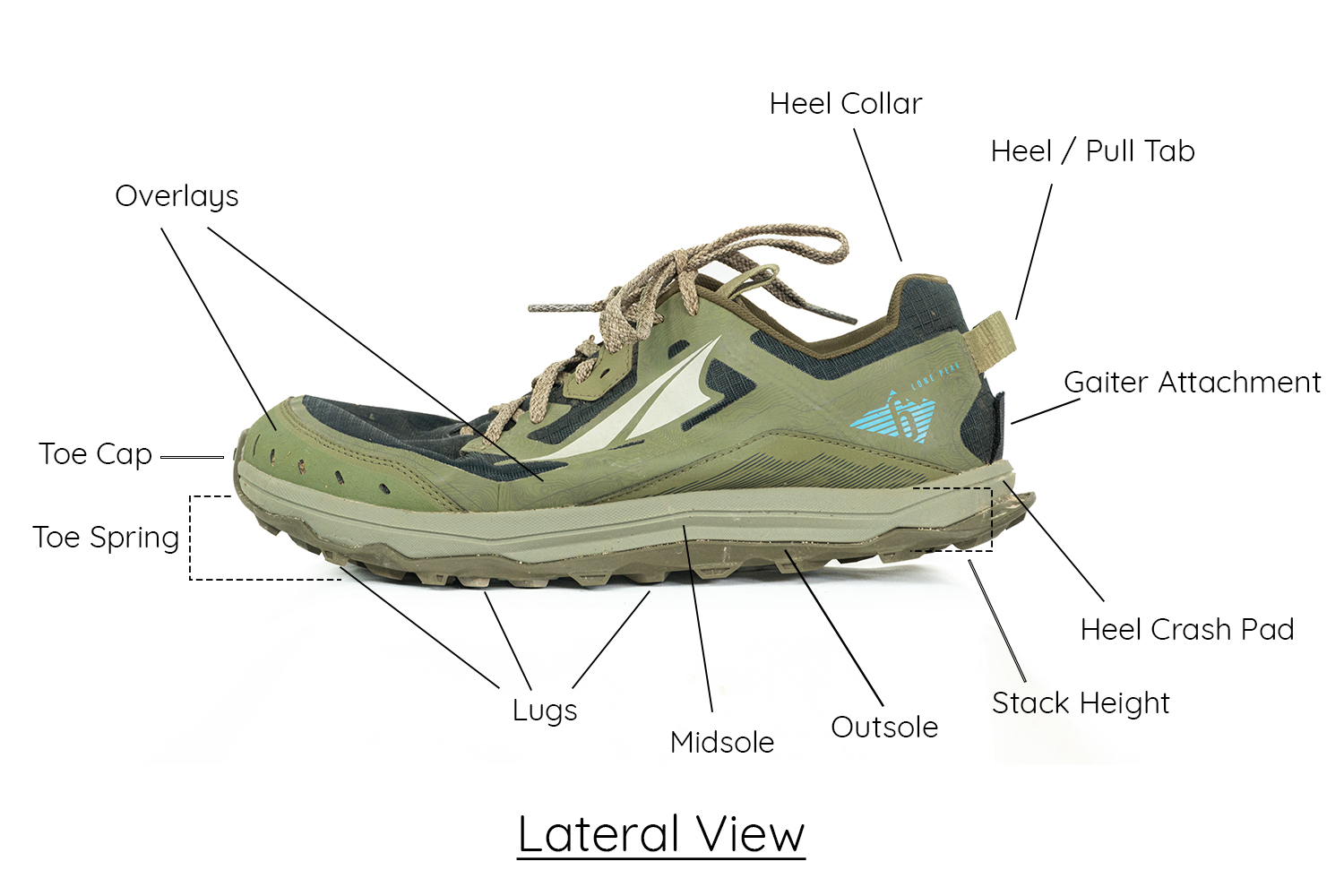

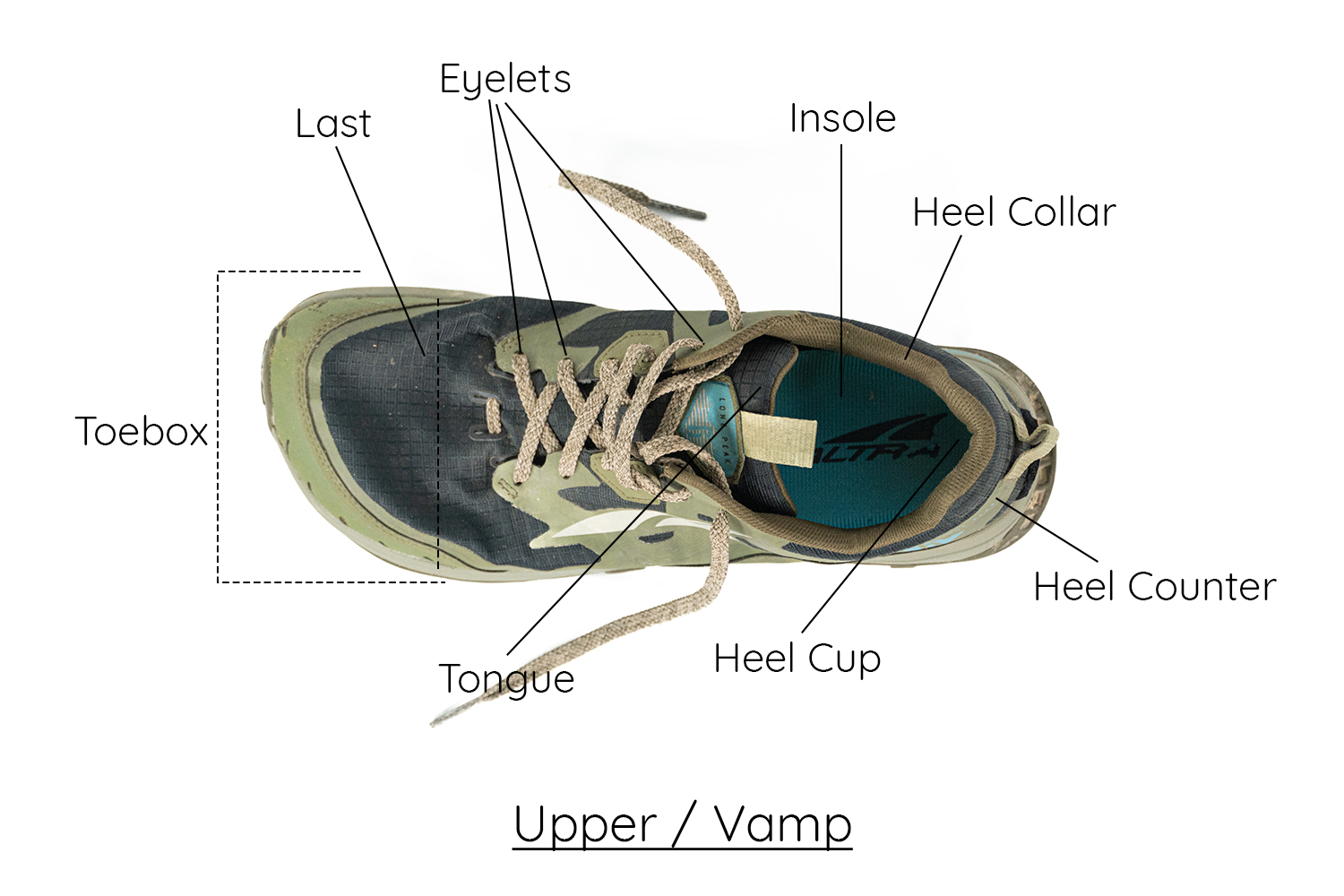

Trail Shoe Anatomy

The human foot is made up of 26 bones, held in place by 30 joints and more than 100 muscles and tendons. These parts work together to steady us through movement. Modern running shoes reflect the foot’s structure with an anatomy of their own. The terms below describe these parts, their location, and their functions (those in italics are represented on the diagram). Getting an idea of these common terms should help make reviews like ours even more useful, and make it easier to research and compare various shoes you might be interested in.

Outsole: The length of textured rubber or exposed foam that lines the very bottom of the shoe from heel to toe. The outsole is what contacts the ground and is responsible for grip, traction, and protection. In trail shoes, this surface is commonly lined with “lugs” of varying size and depth. Some important things to keep in mind when looking at shoes’ outsoles include the rubber compound / type (softer = grippier, harder = more durable) and the size, depth, and layout of the lug pattern. Taller, more spaced-out lugs generally grip better in soft, deep, loose conditions like mud and snow, while shorter, more densely spaced lugs typically equate to better efficiency on firmer, hardpacked surfaces.

Midsole: The layer of material between the outsole and the upper. The midsole is the main part of the shoe that’s responsible for cushioning, energy return, protection, and motion control (pronation / supination). I.e., it’s one of the most important and defining parts of a shoe’s on-trail performance and feel. The midsole runs the length of the shoe and in most cases is made from plastic compounds (typically some sort of foam) of varying densities. Midsoles vary greatly in terms of how they actually feel on trail (e.g., some are super plush / squishy, while others feel very firm), which is why we always discuss the midsole in detail in our full shoe reviews.

Heel Crash Pad: A section of midsole that extends off the back of the shoe below the heel counter. Models stressing stability often make use of this feature to accommodate heel striking. It’s commonly found in maximal shoes (i.e., those with very thick midsoles), and less often in shoes with lower stack heights.

Heel / Pull Tab: Some trail models add a simple pull tab behind the heel to make getting the shoe on easier. This feature is especially helpful on tight-fitting models intended for races or workouts.

Overlay: Found on top of the upper material, overlays are typically synthetic strips of material serving a few purposes when used on trail running shoes: to add protection, increase the stability of the fit, and improve durability. They’re typically either stitched, glued, or heat-welded on. Generally, a shoe with lots of overlays will feel more rigid and supportive through the upper (which can be particularly useful when running on technical off-camber terrain), and potentially be more durable and less breathable.

Toe Cap: A lip of rubber or plastic that extends from the outsole beneath the shoe and attaches to the upper at the front of the toe box. This feature is much more pronounced in trail shoes and functions primarily to protect your toes from rocks and other trail debris.

Toe Spring: The degree to which a shoe’s outsole is curved upwards at the forefoot. Inflexible road shoes make use of this design aspect to encourage proper toe-off during the gait cycle. It is less commonly seen in trail models, but is related to rocker geometry (see below).

Lugs: Small points of raised rubber lining the outsole on most trail shoes. Measured in millimeters, lug lengths and patterns vary depending on the types of conditions the shoe is intended for. Longer lugs (up to 8 mm) are commonly found on models best suited for wet / muddy terrain, whereas models with lugs under 4 mm are often used as road-to-trail shoes.

Gaiter Attachment: Some trail running models offer attachment sites at the heel counter and the bottom of the tongue for lightweight gaiters. These accessories help prevent sediments and other debris from entering the shoe and are especially useful in sandy, dry conditions (as well as deep snow).

Stack Height: The distance between your foot and the ground (in millimeters), measured at both the front and back of the shoe. Stack height is a very valuable metric when thinking about the amount of cushioning a shoe offers. Measurements range from as little as 3 mm in minimal models to excesses of 30 mm in maximal models. Taking the difference between the front stack measurement and the rear stack measurement of a shoe will indicate its heel-to-toe drop (see below).

Heel-to-Toe Drop: Indicates the difference in height (in mm) between the heel and forefoot of a running shoe. These measurements vary from anywhere between 0 to 16. A shoe’s heel-to-toe drop is important when considering gait patterns, muscle recruitment, injury history, distance, and terrain. Typically a lower heel-to-toe drop encourages a more midfoot or forefoot-leading foot strike, while a very high heel-to-toe drop typically encourages a heel-first strike. This is also sometimes simply referred to as “drop.” In the context of trail running, shoes with higher drops tend to provide less ground feel than those with a lower differential, though they may be more comfortable if you heel strike.

Rocker: This refers to shoes that have a rounded midsole geometry designed to “rock” the foot forward through the gait cycle. Some models incorporate this design element from just the toe forward (toe rocker), while in other models, it runs the length of the shoe (heel-to-toe rocker). In theory, rockered sole geometry is included to boost running efficiency. Typically, you see the most radically rockered soles on shoes with thick midsoles / high stack heights. If you’re familiar with the term “rocker” in the context of surfboards, snowboards, or skis, it’s a similar concept in shoes, referring to the way the bottom of the shoe curves upward.

Rock Plate: A thin plastic (and in some cases, carbon fiber) piece located between a trail shoe’s midsole and outsole (or between the midsole and insole). Rock plates primarily serve to shield the foot from sharp objects; however, they often inadvertently add rigidity. In newer models, the use of segmented rock plates enables shoes to articulate without drastically sacrificing protection.

Performance Plate: Included to increase energy return and efficiency, performance plates are typically made from inflexible materials like carbon fiber or certain hard plastics. As of late, their use in popular high-end, speed-oriented road running shoes has spilled over into premium trail models, typically targeted at racers. By virtue of their rigidity, performance plates can often double as protective rock plates.

Heel Counter: Located toward the rear of the shoe, the heel counter is a rigid (often plastic) insert sitting above the heel cup on the inside or outside of the shoe. Wrapping the heel both laterally and medially, its main purpose is to supplement support and motion control by locking the foot into place. Trail shoes tend to have firmer heel counters relative to road shoes to account for the stress placed on that area during steep climbs.

Heel Cup: The basin made at the end of a shoe’s insole backed by the heel counter. This location is also commonly referred to as the Seat of a shoe and is designed to support and secure the back of the foot and the Achilles while running.

Toe Box: Defined as the portion of the upper surrounding the toes and forefoot, toe boxes primarily affect how much your toes can or cannot spread (or “splay”) outward inside the shoe. In trail shoes, they will likely have added material such as welded overlays for protection. For wider feet, finding models with rounded, “foot-shaped” toe boxes can help provide a more accommodating fit, whereas shoes with more tapered toe boxes may provide a more stable fit for those with narrower, more tapered feet / toes.

Last: Technically, this term refers to the mechanical insert resembling a human foot that’s used when a shoe is molded during production. Functionally, it determines the volume and width of the upper and how it attaches to the midsole.

Tongue: Set directly beneath the laces, a shoe’s tongue runs from the vamp to the top of the foot where it meets the heel collar on both sides. Some models feature a Gusseted Tongue, where the tongue is sown into both sides of the upper in addition to being attached to the vamp. Trail models are likely to employ this style to help keep out debris and encourage a tighter, more stable fit since gusseted tongues generally don’t shift around as much as those that are only secured to the upper in one spot.

Eyelet: Simply, the holes through which the laces of a shoe run. These are commonly reinforced with metal, plastic, extra stitching, or reinforced fabric.

Insole: Insoles (sometimes used interchangeably with “sockliner” to refer to the factory insole that comes with the shoe) are thin pieces of material (usually an EVA or TPU foam, or a rigid plastic) positioned above the midsole directly under the foot to enhance the comfort and fit of a shoe. They are often removable, allowing runners to replace them with their own orthotic or aftermarket insole for supplemental support and/or cushioning.

Medial Post: Found on the medial aspect of a shoe and extending from the midsole, this feature is commonly made out of hard plastic and reduces overpronation in models that aim to increase foot stability. In highly cushioned shoes, a medial post can also help offset the unsteadiness resulting from a high stack height.

Upper: Refers to the fabric (often a combination of mesh and protective synthetics) that covers the top of the foot from heel to toe. When considering breathability, water drainage, water resistance, durability, and foot stability, a shoe’s upper construction is very important.

Vamp: A more specific term for the upper of a shoe. The vamp encompasses material from the toe box to the heel collar, exempting the tongue / laces.

This is super helpful, thank you!!!