2022 Rocky Mountain Element

Wheel Size:

- XS: 27.5’’

- S–XL: 29’’

Travel: 120 mm rear / 130 mm front

Material: Aluminum and Carbon versions available

Price:

- Carbon frame w/ Fox DPS Factory shock: $3,199

- Complete bikes $2,559 to $9,589; see below for details

Size Tested: Large

Blister’s Measured Weight: 27.8 lb / 12.6 kg (Element C70, size Large)

Reviewer: 6’, 170 lb / 183 cm, 77.1 kg

Test Location: Washington

Test Duration: 2.5 months

Intro

The prior-generation Rocky Mountain Element was an XC race bike through and through, but Rocky has given the new bike a dramatic overhaul. Rear suspension travel has been increased by 20 mm, to 120, and the Element now comes with a 130 mm fork. But the geometry has changed even more radically, with the headtube angle getting slacker by a whopping four and a half degrees. This clearly isn’t your standard minor redesign, so let’s get right into it.

The Frame

The Element is still available in both aluminum and carbon frames, and Rocky Mountain’s typical “Smoothlink” suspension layout carries over, too. It’s a Horst-link layout with the shock mounted horizontally underneath the top tube, leaving tons of room for two water bottles inside the front triangle on all sizes apart from the XS, which still gets one.

Speaking of that XS frame, it’s the only size of the Element to get 27.5’’ wheels; the bigger sizes are all 29ers. Rocky Mountain (and some other brands) have been taking the approach of putting smaller wheel sizes on smaller frames for a while now, and it makes a lot of sense. Shorter riders have less room to get behind a big 29’’ rear wheel on steeper terrain, and the taller 29’’ front wheel and fork can also be limiting when it comes to getting bars low enough to effectively weight the front wheel.

Rocky Mountain’s full-suspension bikes have typically had a huge amount of geometry adjustment available via their “Ride9” flip chips, and while the Element doesn’t do away with that system entirely, it has been pared down to four settings.

Cable routing is internal, and the Element features rubber guards on the downtube, seatstay, and chainstay. Rocky Mountain’s preferred BB92 press-fit bottom bracket is also here, as well as a SRAM UDH derailleur hanger.

Fit & Geometry

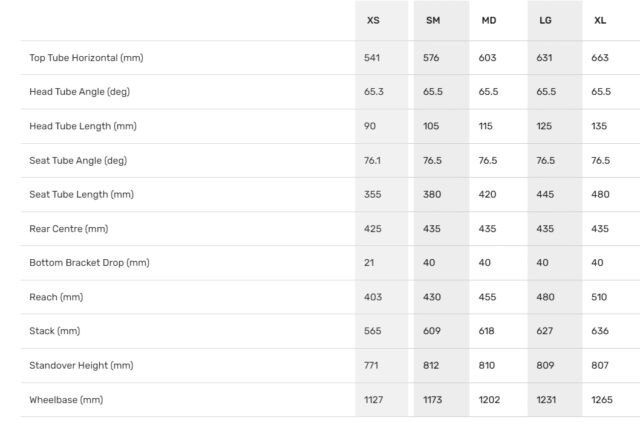

The Element is still available in five frame sizes, though the nominal sizes have been shuffled around a bit. There’s now an XS on offer, and the XXL from the prior bike is no more. If you ignore the size names and compare the equivalent spots in the range (e.g. the new XS to the old Small, or new Medium to the old Large, etc.) the reach hasn’t actually changed a whole lot, apart from growing by 15 mm in the largest size. What has changed, dramatically, is the headtube angle — it now sits at 65.5° in the neutral position, almost 4.5° slacker than the old bike (69.8°). That’s a massive difference, and one that should go a long way in transforming the Element from a classic XC race bike to something much more capable in more technical terrain. The “slack” position on the new Element shaves 0.5° off those angles, and the “steep” one adds 0.3°.

The seat tube angle has been steepened a touch, to 76.5° for the 29er sizes and 76.1° for the XS. The XS bike gets 425 mm chainstays, which grow to 435 mm on the other sizes. All of that adds up to wheelbases that range from 1127 mm on the XS through 1265 mm on the XL. The Element’s sizes also cover a huge range; Rocky Mountain recommends the XS frame for riders as short as 4’8’’ (143 cm) and the XL for folks up to 6’6’’ (198 cm). For reference, the full geometry chart is below.

Between adding a bit of suspension travel and that dramatically slacker headtube angle, the new Element should be a whole lot more capable and forgiving on descents than the outgoing model. Where it previously was a true XC race bike, the new model at least looks to be much more of a short-travel Trail bike, along the lines of the Transition Spur, Guerrilla Gravity Trail Pistol, Pivot Trail 429, and so on.

The Builds

Rocky Mountain offers the Element in seven different complete builds, at a very wide range of prices. The base Element Alloy 10 starts at just under $2,600, and the top-spec Element Carbon 90 will run $9,589. The highlights of all the build levels are below.

- Fork: RockShox Judy Silver 130 mm

- Shock: RockShox Deluxe Select

- Drivetrain: Shimano Deore w/ SunRace Cassette

- Crankset: Rocky Mountain Microdrive

- Brakes: Tektro HD-M275

- Wheels: Rocky Mountain TR25 rims, Shimano MT400 hubs

- Dropper Post: Rocky Mountain Toonie

- Fork: RockShox Recon Gold 130 mm

- Shock: RockShox Deluxe Select+

- Drivetrain: Shimano Deore

- Crankset: Shimano Deore

- Brakes: Shimano MT4100

- Wheels: WTB ST Light i27 rims, Shimano MT410 hubs

- Dropper Post: Rocky Mountain Toonie

- Fork: Fox 34 Performance, 130 mm

- Shock: Fox Float DPS Performance

- Drivetrain: Shimano SLX w/ XT rear derailleur

- Crankset: Race Face Aeffect

- Brakes: Shimano SLX

- Wheels: WTB ST Light i27 rims, Shimano SLX rear hub

- Dropper Post: Rocky Mountain Toonie

- Fork: Marzocchi Z2, 130 mm

- Shock: Fox Float DPS Performance

- Drivetrain: Shimano SLX w / Deore cassette

- Crankset: Shimano Deore

- Brakes: Shimano MT4100

- Wheels: WTB ST Light i27 rims, Shimano MT410 hubs

- Dropper Post: Rocky Mountain Toonie

- Fork: Fox 34 Performance, 130 mm

- Shock: Fox Float DPS Performance

- Drivetrain: Shimano XT w/ SLX cassette

- Crankset: Race Face Aeffect

- Brakes: Shimano SLX

- Wheels: WTB ST Light i27 rims, DT Swiss 370 rear hub

- Dropper Post: Rocky Mountain Toonie

- Fork: Fox 34 Performance Elite, 130 mm

- Shock: Fox Float DPS Performance Elite

- Drivetrain: Shimano XT

- Crankset: Shimano XT

- Brakes: Shimano XT

- Wheels: WTB ST Light i27 rims, DT Swiss 370 rear hub

- Dropper Post: Race Face Turbine R

- Fork: Fox 34 Factory, 130 mm

- Shock: Fox Float DPS Factory

- Drivetrain: Shimano XTR

- Crankset: Race Face Next SL

- Brakes: Shimano XTR

- Wheels: Rocky Mountain 26XC Carbon, DT Swiss 350 rear hub

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer Factory

Those are enough options that there should be something for everyone here, though it is a little disappointing to see details like a house-brand front hub on even the top-tier Carbon 90. But a number of the more affordable builds are fairly solid value for money, and it’s great to see such a wide range of builds on offer.

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) The new Element is slotted squarely against the class of aggressive short-travel bikes like the Transition Spur, Guerrilla Gravity Trail Pistol, and Pivot Trail 429, but how does it actually stack up on the trail?

(2) That said, is the Element still a viable option for the occasional — or frequent — XC race, too? Or is it more of an everyday Trail ride for an XC-minded rider, and an option for longer, more technical sorts of endurance races?

Bottom Line (For Now)

The Rocky Mountain Element has undergone a dramatic transformation for 2022, and the new bike looks like a really excellent option for logging huge miles while still maintaining a whole bunch of capability in more technical terrain, too. We’re hoping to be able to line up the Element for a full review in the future to see how it really compares to the alternatives on the trail.

FULL REVIEW

I wasn’t totally sure what to expect from the new Rocky Mountain Element — on one hand, Rocky calls it an XC bike, and the prior generation unquestionably was one. But on the other hand, the new bike’s got a 65° headtube angle, and the travel has been bumped up to 120 mm in the back, and 130 mm up front. In fact, the geometry isn’t all that different from the Altitude, the 160 mm / 170 mm travel bike that Rocky Mountain’s EWS team is racing on. But on the other … other hand, it’s got a fairly lightweight build and a lot of XC-oriented parts bolted to it. How was that all going to add up? I really wasn’t sure.

Having now spent a few months on the Element, it does indeed offer a unique blend of traits — but a blend that feels totally coherent, and is really going to click for the right riders.

Fit & Sizing

Rocky Mountain’s size chart puts me (6’ / 183 cm tall) right in the middle of the range for a size Large Element, and that was definitely the right call. At 475 mm (slack geometry position), the reach of the Element is a touch shorter than I’d generally prefer on a bigger Enduro bike, but for a more XC-oriented option, it felt like a great fit, particularly given the slightly more moderate 76° seat tube angle and the 632 mm effective top tube length that results. The bottom end of the recommended size range for the XL starts at 6’1’’, and while I think I probably could stretch myself onto one okay, I’m really not that interested in trying. If this was a bike that was supposed to be super stable and intended to plow through stuff in a straight line, maybe. But for a more XC-oriented bike, the Large Element fits me great.

I did swap in a bar with less backsweep than the stock Rocky Mountain branded one (9° bars tend not to agree with my wrists) but stuck with the stock 780 mm width and 50 mm long stem. Those both felt like sensible sizes for a bike that’s sort of blurring the lines between a short-travel Trail bike and a very aggressive XC one.

I also appreciated that, despite their clear emphasis on minimizing weight in the build spec, Rocky Mountain still put a 175 mm drop Fox Transfer post on our size Large test bike (and between the moderate seat tube length and deep insertion depth, I easily could have cleared the 200 mm version, but 175 mm felt totally adequate for this sort of bike). The Element is light and efficient, yes, but it’s not just light and efficient.

Climbing

As you’d hope for from a fairly light short-travel bike, the Element climbs extremely well, and not just in the sense that it’ll get you to the top without much fuss. The Element is very efficient and eager to put down power wherever possible — it’s a bike that really encourages you to climb quickly and push the pace where you can.

I found myself using the climb mode on the Fox DPS shock regularly, though the Element still pedals well without it. But given how efficiency-oriented and sprightly the Element is, I typically wanted to really lean into that character and hammer when I had the opportunity (and was feeling fresh enough to). The fork climb switch, on the other hand, I rarely used at all. Especially on a relatively short-travel fork with a correspondingly stiff setup, there’s just so little suspension movement anyway (so long as your pedal stroke is at least somewhat smooth) that it didn’t feel helpful, and in fact, had a tendency to make the fork ride higher in its travel in a way that I found detrimental. I’ve generally not been a fan of fork climb switches for those exact reasons, and the Element didn’t do much to change my mind — and its pedaling performance is truly great without one.

The pedaling position also feels especially dialed, given the intentions of the Element. Ultra-steep seat tubes are great if you’re just grinding up an extended climb, but can feel more awkward for seated pedaling on flatter ground, and can also make it less smooth to go back and forth between seated and standing climbing. The Element strikes a great balance between being steep enough to keep the front wheel planted on steeper climbs, while still feeling natural on flatter trails and very seamless to hop out of the saddle and sprint — and given how well the Element pedals, doing so produces great results.

The handling of the Element — both uphill and downhill — works best with a somewhat lower bar setup and correspondingly forward stance, which also helps with the Element’s climbing prowess. By not needing a mega-steep seat tube to climb well, Rocky Mountain has done a great job of making a bike that doesn’t require major compromises in cockpit setup to emphasize either climbing or descending performance. It’s a super cohesive design that works and fits very well for its intended purpose. And it’s not like the Element’s seat tube is slack by any reasonable definition of the word; it’s just dialed back a little from a lot of modern winch-and-plummet style Enduro bikes.

Unsurprisingly, given the Element’s relatively firm suspension and very efficient climbing performance, it does feel somewhat less planted and doesn’t offer as much traction under power as some generally cushier, less sprightly feeling bikes (even ones with similar travel), but I think that’s an entirely reasonable tradeoff for how well it puts down power. The Element is a good technical climber if ridden fairly precisely, but folks who want something to make really rough, technical climbing (comparatively) easy are generally going to be better off with something a bit more plush and planted, and likely with a little more suspension travel. That will definitely come with tradeoffs in terms of efficiency and speed, though, so it’s a good time to know thyself and think through what you really want out of your bike. For riders who are more focused on efficiency and putting down power effectively, the Element is excellent.

Descending

I’ve said before that short-travel Trail bikes — even ones that look similar on paper — can differ pretty significantly. Some can feel derived from a longer-travel, more aggressive bike that was dialed back and made with less suspension, while others can feel like an XC bike that’s been stretched longer and slacker, and given a bit of extra squish. The Element is definitely in the latter camp, but it’s still a very good descender in the hands of the right rider.

The Element does feel somewhat XC-derived in a lot of respects, and it isn’t a bike that is going to simply mow down aggressive descents without some precise piloting. But, crucially, it does have the geometry to give you a whole lot more room to work with the bike, and a much bigger sweet spot than most shorter, steeper true XC bikes. So if you want your short-travel Trail bike to feel precise and sharp-handling, but with a platform that is long and stable enough to push a lot harder than a more traditional XC bike, the Element is excellent.

The tradeoff with the Element’s notably long, slack geometry is that, compared to a lot of other bikes in its travel class, it’s not as engaging on flatter, more mellow trails — it’s a bike that wants to be pushed fairly hard to really feel in its, uh, element (sorry). The geometry adjustment offered by the Ride4 system does mellow the Element out to some extent at the steeper end of the adjustment range, but it doesn’t bring about a wholesale change to the bike or anything like that; the steeper settings are a little quicker-handling and a touch less stable, while the slacker ones make the bike a bit more composed at speed, but require a little more to come alive.

In terms of suspension performance, the Element once again feels on the firmer, more supportive end of the spectrum, as opposed to feeling more planted and cushy (for its travel range; it’s a 120mm-travel bike, after all). Small-bump sensitivity isn’t particularly the strong suit of the Element, but it’s not unduly harsh or anything like that. The Element just feels like it’s displaying the normal tradeoffs that you get when making a bike where pedaling efficiency and liveliness are real priorities of the design. That said, I do think the Element’s suspension would likely work better if it were a little less progressive (especially at the slacker end of the geometry adjustment range, where it gets more progressive). My hunch is that a bit flatter leverage curve would make the bike feel more supportive through the midstroke without making it too hard to use something close to full travel, and leave a bit more of the limited to total travel on the table, rather than settling in relatively deep and then slamming into the substantial progression deep in the stroke.

The build definitely contributes here, too. Rocky Mountain has gone for a build spec that puts a clear emphasis on minimizing weight (within reason) and a few different choices, build-wise, make a significant difference in the overall character of the bike. So on that note:

The Build

Deciding on the spec for the Element can’t have been easy. On the one hand, it’s still the most XC-oriented bike in Rocky Mountain’s lineup and is supposed to be light, efficient, and quick. On the other hand, it’s got a lot more suspension travel and radically more aggressive geometry than the bike it replaced, and on paper looks like it could be a very good everyday Trail bike for a lot of folks. So how did Rocky Mountain do at walking that particular tightrope?

Overall, what they’ve done feels coherent, but hews significantly toward the XC end of the spectrum. Depending on your priorities, that may or may not be a good thing. As built, the Element feels like a bike for riders whose priorities are (1) being light and efficient and (2) having a more stable, forgiving ride than traditional XC race bikes, in that order. And so if you’re all about logging huge days in the saddle and covering a lot of ground quickly, the Element is outstanding, and the builds that Rocky Mountain has put on it make perfect sense. You get things like a Fox 34 fork with the Fit4 damper (which features a climb mode), fast-rolling Maxxis Recon tires at both ends, a straight-body Fox DPS shock, two-piston brakes, and so on — stuff that’s aimed at being light and efficient, first and foremost. But what about the folks who see the 65° headtube angle and think that the Element sounds like it could be a killer short-travel Trail bike?

I’m honestly kind of surprised that Rocky Mountain doesn’t offer a beefed-up “BC Edition” of the Element, as they have on prior versions of their bikes. To be clear, I don’t think the choices that they’ve made are bad ones for a lot of folks who would consider the Element, but the option for a burlier build would open up its appeal to a whole different segment of riders who might be drawn to what could still be a fairly light, snappy short-travel Trail bike with notably aggressive geometry for the category, but who would prefer burlier brakes, tires, and suspension on such a bike.

And so to that end, I did a bit of experimenting with a home-brew BC Edition, of sorts. The first things I swapped out were the tires, experimenting with both just putting a Maxxis Dissector up front, in place of the stock Recon, and with moving that Dissector to the back and trying a Maxxis Minion DHF up front. The effects were fairly predictable — each step up offered more grip, at the expense of some weight and (especially) rolling efficiency. Particularly given the long, wet spring and early summer we had in Western Washington, I wound up running the DHF/Dissector combination more than the other two, but went back to the Dissector/Rekon for a bit later in my testing once things finally dried out a bit. The Rekon works well as a fast-rolling tire for dry hardpack conditions but quickly starts to feel like a limiting factor for what the Element can do when things get looser and/or wet, especially up front.

I also definitely would have preferred that Rocky Mountain spec the Grip2 damper in the Fox 34 fork over the Fit4 that they opted for. The Grip2 is marginally heavier and lacks the three-position climb mode of the Fit4, but its performance on the way back down is so much better as to be clearly worth the tradeoff, at least in my estimation. I didn’t have a Grip2 34 handy to swap in but instead used the Element as the platform to kick off my testing of the new Öhlins RXF34 m.2 (review coming soon), which was a big improvement. I get that some folks definitely want the climb switch of the Fit4, hence my hope for a BC Edition build — give that one a Grip2 and everybody’s happy.

I didn’t have an opportunity to try a heavier-duty rear shock on the Element, but I’d be curious to try the Fox Float X on it. The Fox DPS shock that came on the Element actually worked pretty well for me — It felt like less of a limitation than the fork, for sure — but I think it would still make sense to spec its bigger brother on this hypothetical BC Edition build. Round that out with some bigger tires, at least a 203mm front rotor (if not the 4-piston version of the Shimano XT brakes), and some more stout tires, and I think Rocky Mountain would really be onto something.

Finally, I used the Element as a platform to start my testing of the new Reynolds Blacklabel 329 Trail Pro wheels (review also coming soon). While I didn’t have any specific issues or gripes with the stock wheelset, the weight loss going to the Reynolds wheels (which are under 1,600 g for the pair, including tape and valves) was quite noticeable and did a lot to accentuate the energetic pedaling performance of the Element. It’s a great candidate for a super light carbon wheel upgrade, given how well it encourages you to really attack on the way up, instead of just moseying to the top.

It’s a seemingly small detail, but I’m also a huge fan of the bottle mount layout on the Element. It’s got two sets of mounts on top of the downtube, one in front of the other (except on the XS Alloy frame, which has to move one of those mounts underneath the downtube), and the carbon models in all but the smallest sizes actually add a third boss to the lower mount. With that extra mounting point, you can either mount the cage a little higher up the downtube where it’s easier to reach (using the forward and middle bosses) or move it down lower (using the middle and lower mounting positions) to make more clearance for a second bottle on the upper set of mounts. It’s a clever arrangement and one that makes a ton of sense, especially for a bike that’s as adept at logging huge miles over long days in the saddle as the Element.

As per usual for Rocky Mountain, the frame finish and build quality are also excellent. The rubber chainstay guard is one of the best-fitting and most effective stock options I’ve come across recently, and all the pivot hardware and other such details are super clean and well thought out. The frame design is also quite striking — the extremely thin top tube, in particular really stands out. It’s a sharp-looking bike.

Comparisons

This is a pretty good comparison, but the Element feels a little more stable and not quite as quick-handling at lower speeds and in tighter spots (especially at the slacker end of its geometry adjustment range). The Element frame also feels a bit stiffer, especially in the rear triangle. Both pedal very well, but if anything the Element is (marginally) even more efficient. These two are definitely different twists on the same sort of bike, though — the Spur is one of the closer comparisons here.

Both bikes pedal quite well, but the Ripley feels a little more plush and has a touch more traction under power than the Element. The bigger difference is in geometry — the Element is quite a bit longer and slacker, and feels like it. It’s more stable at speed but takes a little more effort to muscle around in tighter spots, and doesn’t feel as engaging on tighter, more rolling trails. The Ripley is a bit more versatile and easy-going on more mellow, XC-type trails; the Element is more capable of going fast on steeper, more technical ones, provided that you ride it fairly precisely.

I tested the LT version of the Occam, rather than its shorter-travel sibling, but they share a frame and so I can make some fairly well-educated guesses here — it’s really just the builds that differ between the Occam variants. The Occam and Element have some real similarities in terms of suspension performance in that they’re both extremely efficient but give up some sensitivity and plushness to get there, through the Occam has notably more travel, with 140 mm at both ends.

But despite that, the Element is actually a little more stable at speed and a little less nimble in tight spots. If you like the sound of the Element, but want a version that’s a bit more plush (mostly due to just having more travel) and a little more easy-going while still pedaling extremely well, the Occam would be a great choice. The Element is the way to go for folks who really want to go fast all the time.

Santa Cruz Tallboy

I don’t have a ton of time on the current Tallboy, but my early impression is that the two bikes are largely reminiscent of each other in terms of handling, especially with the Element at the steeper end of its range. The bigger difference is in suspension performance — the Tallboy still pedals quite well, but it’s a little less snappy than the Element, and makes up for it with significantly more plush-feeling suspension. The Tallboy is, of course, still a short-travel bike — don’t expect it to feel like it’s got a lot more suspension than it does — but it’s notably cushier than the Element.

Unfortunately, we don’t have any reviewers who have spent time on both the Trail 429 and the Element, but from chatting with our folks who’ve ridden the Trail 429, the two sound fairly similar, particularly with the Element at the steeper end of its geometry adjustments, and the Trail 429 in the slack one. My hunch is that the Trail 429 is going to be a little more easygoing and versatile overall, while still quite quick, and the Element is a little more game-on and always in attack mode, but we’ll need to get one of our reviewers to spend time on both to confirm.

It is worth noting that Pivot offers both standard and “Enduro” versions of the Trail 429, which share a frame but differ in terms of parts spec. It’s not a perfect one-to-one, but the Trail 429 Enduro builds would be a really good call for someone who’s into the idea of my hypothetical Element BC Edition but doesn’t want to piece one together themselves (you can read our review of the Enduro version of the Trail 429 for more on that bike).

I haven’t personally ridden the Phantom either, but from talking with our other reviewers about it, it’s pretty clear that the Phantom is more plush and planted, but not as light or efficient as the Element. Both are relatively stable for a 120mm-travel Trail bike, but the Phantom sounds like the better choice for folks who want a relatively forgiving, descending-focused short-travel bike, whereas the Element is more high-strung and efficient, but not as plush and easy-going for it.

Guerrilla Gravity Trail Pistol

The Trail Pistol is in a similar boat as the Phantom — it’s less efficient and XC-derived than the Element, but more planted and forgiving, and doesn’t take as much precision to stay composed in rough terrain. They’re not far off from each other in terms of stability if you’re riding cleanly, but the margins for error feel bigger on the Trail Pistol. The efficiency tradeoff is very real though — the Element pedals quite a bit better (and is a lot lighter), even with a lighter build on the Trail Pistol than I had for the bulk of my review (see the link above for more on that).

Who’s It For?

The Rocky Mountain Element is an outstanding short-travel Trail bike for riders who really want to push hard and go fast everywhere — whether the trail is pointed up or down. It’s not the most easy-going or engaging at lower speeds, but it both pedals especially well and has the geometry to go hard on the way back down, provided that you’re riding with some precision. Folks looking for a cushier-feeling or more easy-going Trail bike are probably better off elsewhere, but for the go-fast set, the Element is an impressive weapon.

Bottom Line

The Rocky Mountain Element is fast. It’s a bike for folks who want to push the pace all over the mountain and offers a somewhat rare blend of XC-derived efficiency and pedaling position with a much longer wheelbase and more stable geometry to get there. It’s still a short-travel bike — folks who are hoping for an ultra-efficient bike that also irons out rougher trails very effectively are, frankly, kind of looking for a unicorn. But the Element is impressively capable of being ridden fast on difficult trails in the hands of a skilled rider who’s willing and able to take an active approach and ride precisely to make it happen.

It would be cool to see Rocky Mountain add a beefed-up BC Edition build down the line (especially if the supply chain headaches in the bike world continue to ease up). But for folks who either want a super light, efficient bike first and foremost, or those who are willing to make some tweaks to open up a bit more aggressive descending capability, there’s a lot to like in the Element.

Thanks for writing this David. It’s super helpful to me as the Element is one of the bikes on my current shortlist.

Question on the geo, specifically the standover height. Based on the geometry chart, the standover height of a medium at 810 mm is quite high relative to the comparison bikes you listed – Ibis Ripley (712 mm), Transition Spur (667 mm), Pivot Trail 429 (670MM). Given the 5.5″ delta between the Spur and the Element, I’m guessing that it’s purely due to the variability in how each manufacturer measures standover height. Or is it really that much of a difference between the other bikes?

Thanks in advance from me and the others in the stumpy inseam club. i.e., Does Luke Koppa give the Element a thumbs up on the standover height?

I think it has to mostly be down to how the different companies measure standover. I didn’t notice the Element’s to be notably high, and, to use the Spur as an example, they’ve both got similar headtube lengths, seat tube lengths, and straight top tubes with a moderate bit of seat tube above the top tube. It’s hard to imagine where you’d get anything close to 140mm difference out of that with a truly apples-to-apples measurement.

Must be something with inconsistent measurements. It looks like a BMX bike with the seat dropped all the way. Certainly no nutbusting top tube on this thing.

you don’t have to look very long on the Rocky Mountain Owner’s group page to find people you’ve created their own BC Editions with swapping to a 140 mm travel fork and some over stroking the shock to a 190×50 (up from the stock 45 mm stroke). My riding buddy got an Element at the start of the season and since put a lighter wheel set, a 140 mm travel 2023 Pike Ultimate, and shorter 35 mm stem to improve the fit of the size large for his 5’10” frame. Making these changes helped improve the descending performance while still maintaining it’s snapping/lively feel. It’s a surprisingly capable bike that is able to be morphed to fit the elements that you ride in.

Great review, David, but if you’re going to be hanging all those more-burly parts off this bike I think I’d just buy an Instinct. The Element is aimed at being a sorta burly xc bike — or an ideal endurance racing bike.

On forks, the best bet for me with Fox forks is the Grip damper. Gives you the near-lockout of the Fit4 and is even more plush than the Grip2. For me Grip2 begins to be essential on a true chunk/enduro bike, which the Element is not.

But….it appears that Rocky will sell every one of these they build, just the way they are. I’ve heard June 23 delivery estimates? Hoping that’s wrong.

Hey Tom,

That’s a big part of what I was trying to get at in the review — the Element would definitely be great as an endurance race bike or burly XC bike as is. But I stand by thinking that it’d be a more appealing short-travel Trail bike for a bunch of people if there was also a BC Edition as an *option*. Plenty of folks would rightly prefer the standard one, but there are good reasons to be interested in a beefier build, too.

Absolutely agree they should offer a BC Edition. In fact, I’d be surprised if they don’t, eventually.

I love 120 bikes for endurance racing, but……the young, flexible guys that win the overall always seem to be on 100 mm bikes, and often hardtails. Having done ONE hundred miler on a hardtail, I can say, firsthand, ouch!

One comparison I’m really curious in is the new trek top fuel. Any insight on this? Re plushness vs efficiency, where their individual strengths lie?

Hey guys!

Looking for some buying advice. I’m looking for a bike that I can take on longer rides and races that is not a hardtail and not heavy FS bike. I have a hardtail and a 140mm rear and front travel bike currently and looking something in between. I’m a pretty heavy rider and ride hard. I have the spur, element, and 429 in mind and having a hard time deciding between those 3. I ride mostly in Phoenix, AZ (Pivots headquarters) where its rocky and loose. which one of the 3 bikes would you recommend for me?

Thanks!

Hi, Amir — for years now, we’ve been getting too many gear questions to be able to respond to them all, so we created our Blister Membership.

So if you’d like to become a Blister Member, you can submit any gear questions through the Blister Member Clubhouse page, and our reviewers will work 1-on-1 with you to make sure you get the right gear for you.

Here’s more information about the Blister Membership and how to sign up: https://blisterreview.com/shop/blister-membership

Hey Dylan,

I’m really thinking about it as I’m having a hard time deciding on a bike. Between my wife and I, we have over 20 subscription’s and its getting out of hand. Looks like a really cool membership, just not sure how much I would use it. Will be emailing you guys if i decide to get one. Thanks!

The ‘downcountry’ moniker is strictly marketing. I’m glad you used the term trail bike. I have a 2022 element and my girlfriend has a V2 Ripley both of us ride XL frames. The 2022 element is as far from an XC bike as it is from an enduro bike – fitting perfectly in the trail bike category. The 120/120 Ripley is slightly faster on most loops I ride. However the Element is certainly a more capable on the downhills – it’s much more muted and less playful than Ripley while being extremely stable at speed preferring more strait lines, similar to how I ride my 160/160 bike. The descending has actually led me into some crashes as I can ride it like my enduro bike and end up finding the traction limit of my Ground Control tires pretty quickly (completely user error). I love the bike as I do not race XC but really enjoy pedaling 4-5 hour days fairly regularly and rarely go to a bike park or shuttle. It is so much more enjoyable on long days with black rated downhills than equivalent long days on the 160/160 bike.

Thanks Stew!

That’s exactly what I’m looking for is a bike that I can take on longer rides, do some races with, and still hit some blacks and rough downhills. Sounds like the element fits that category just wonder how it compares to the other 2 I’m looking at. The spur and the 429.

Would this compare to the Kona Hei Hei since the Hei Hei is also a 120mm bike? There’s not many articles that go in depth about the Kona.

Nice review. I’m always interested in how well the pivots hold up. I have a Revel Rascal that has 18 pivots and gets noisy if the pivots are not changed annually.

In how much travel does it reslut if you overstroke 5mm?

Didnt find something but I think up to 190×50 shock won t cause in trouble..