Forbidden Dreadnought

Test Location: Washington

Test Duration: 2 Months

Wheels: 29′′

- Mixed configuration possible with interchangeable suspension link

Travel: 154 mm rear / 170 mm front

Geometry: See Below

Size Tested: Large

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- Frame Only (w/o shock or chainguide, including axle and seat clamp): 2,748 g / 6.06 lb

- Fox Float X2 rear shock: 685 g / 1.51 lb

- Chainguide: 132 g / 0.29 lb

- Total: 3,565 g / 7.86 lb

- Complete bike, as built (w/ RockShox ZEB Ultimate, w/o pedals): 15.1 kg / 33.4 lb

MSRP:

- Shimano SLX Build: $5,699

- Shimano XT Build: $7,399

- Frame + Fox Float X2 Performance: $3,599

- Frame + EXT Storia: $4,299

- Frame + Push ElevenSix: $4,399

Intro

This February Forbidden released the Dreadnought, the longer-travel stablemate to their 130mm-travel Druid. The Dreadnought, with 154 mm of rear-wheel travel, does get the longer / slacker treatment that you’d expect, but there’s a lot more going on here than just another ~155mm-travel Enduro sled (in a market already full of variants on that theme).

Also, “Forbidden Dreadnought” is now both my early frontrunner for Product Name of the Year, and the name of my soon-to-be-formed metal band.

Anyway, I’ve now spent the past couple of months riding the Dreadnought and comparing it to a bunch of other bikes in this category, so it’s time to weigh in:

The Frame

The Dreadnought frame bears a strong family resemblance to the Druid. Both are available in carbon fiber only, and share a nearly identical silhouette, the most obvious feature of which is a high-pivot suspension layout, with an idler pulley located above the crankset.

The high single-pivot suspension layout gives the Dreadnaught a rearward axle path through the entirety of the travel, which Forbidden says improves absorption of square-edged hits. The idler pulley mitigates the extreme chain growth that the high-pivot layout would otherwise induce, and allows Forbidden to fine-tune the bike’s anti-squat to achieve their desired pedaling characteristics, without resulting in significant pedal kickback.

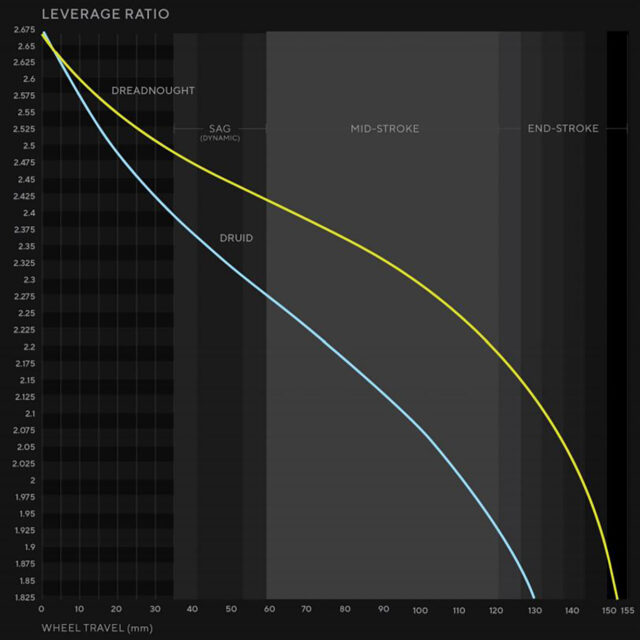

The leverage curve of the Dreadnought is quite progressive, starting at about 2.65:1 at topout, and reaching 1.825:1 at the end of the stroke. While there aren’t any crazy undulations in the leverage curve, it’s not quite a straight line either; the curve flattens out a bit through the midstroke, and becomes notably more progressive in the last 35 mm or so of travel. Anti-squat sits around 120% at sag, and tails off gradually to around 95% by the end of the stroke.

The shock (a 205 x 65 mm Trunion size) is mounted low in the frame of the Dreadnought, just above the bottom bracket, which both lowers the bike’s center of gravity, and preserves room in the front triangle for a full-size water bottle on all sizes. A second set of mounts underneath the top tube are meant for a tool, a pump, or other such accessories.

The Dreadnought features internal cable routing throughout, a threaded bottom bracket shell, and post-mount brake tabs for a 180 mm brake rotor. The lower two mounts for a standard set of ISCG ‘05 tabs are included (the idler pulley isn’t compatible with a standard upper guide, hence the omission of the top mount) and Forbidden includes an e*Thirteen bash guard and lower guide with all Dreadnought frames and complete bikes. The idler pulley gets its own, integrated top guide for chain retention, and large rubber guards are included on both the swingarm and the downtube.

The stock configuration for the Dreadnought is to be run with 29” wheels at both ends, but Forbidden offers an aftermarket “Ziggy Link” for riders who want to try a 27.5” rear wheel for a mullet setup. The Ziggy Link preserves the stock geometry, and is shared with the Druid if you’re mullet-curious with one of those as well.

Forbidden also notes that the Dreadnought is rated to be run with a dual-crown fork, if desired. While not everyone will want to (or should) take them up on that, I think pedaling a dual crown uphill is a lot more reasonable than conventional wisdom might suggest, and the fact that Forbidden has given their blessing is a welcome option.

The Builds

For now, the Dreadnought is available as a frame only, with your choice of an EXT Storia or Push ElevenSix rear shock. A Fox Float X2 will also be available on Dreadnought frames sometime in Q2 of 2021, along with a complete bike spec’d with a Shimano XT drivetrain. A Shimano SLX complete build is to follow in Q3.

The specs of the forthcoming complete offerings are as follows:

SLX Build ($5,699):

- Fork: RockShox Zeb Select+

- Rear Shock: Fox Float X2 Performance

- Drivetrain: Shimano SLX

- Brakes: Shimano SLX 4 Piston

- Wheels: Shimano SLX Hubs / e*Thirteen Rims

- Dropper Post: e*Thirteen Vario

XT Build ($7,399)

- Fork: Fox 38 Performance Elite

- Rear Shock: Fox Float X2 Performance Elite

- Drivetrain: Shimano XT

- Brakes: Shimano XT 4 Piston

- Wheels: DT Swiss 350 Hubs / e*Thirteen Rims

- Dropper Post: Bikeyoke Revive

The current frame-only offerings are available in either “Stealth” (a matte black finish) or “Deep Space 9” (a glossy black to blue fade). Stealth will be the lone color for the XT build, with Deep Space 9 featured on the SLX bike. A third, frame-only colorway, dubbed “Nerds” (a metallic blue to purple fade) will be available in Q2 of 2021.

Fit and Geometry

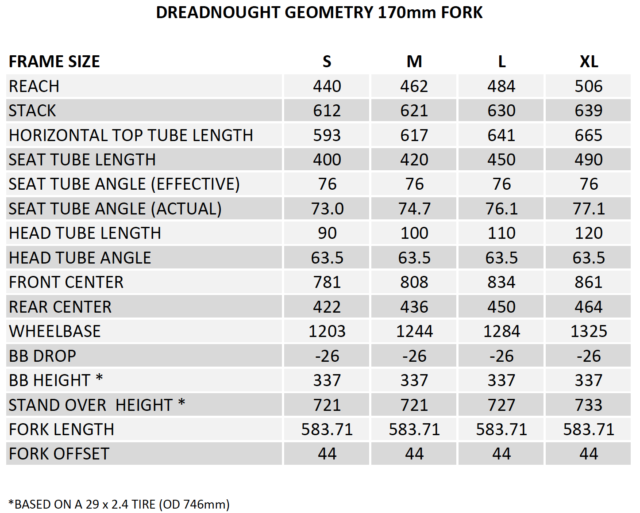

Forbidden offers the Dreadnought in four sizes, from S through XL, which reach figures ranging from 440 to 506 mm in 22 mm increments, and their recommended sizing covers riders between 5’2” (158 cm) and 6’6” (198 cm). Forbidden also varies the length of the chainstays between sizes, a move that is growing in popularity, and that we at Blister have been applauding for some time.

Interestingly, the Dreadnought makes far bigger steps between sizes than average, with the chainstays growing by 14 mm per size, from a very short 422 mm on the size Small, through a massive 464 mm on the XL. Forbidden says that they are the “only brand to ensure the same weight distribution across all sizes”, and there might be something to that, at least in terms of the ratio of chainstay length to total wheelbase. The Dreadnought maintains the same ratio across the full size range, a rare thing even for companies that do vary chainstay length between sizes.

All sizes get a 63.5° headtube angle and a 76° effective seat tube angle. Despite varying the chainstay length between sizes, all four use the same swingarm; the chainstay length is varied by moving the bottom bracket relative to the rest of the front triangle. The result is that the actual seat tube angle on the Dreadnought ranges from 73° on the Small, through 77.1° on the XL, making the L and XL sizes the exceedingly rare bikes that have a steeper actual seat tube angle than their effective seat tube angle.

All of that adds up to wheelbases that range from a fairly short (for this class of bike) 1203 mm on the Small frame, through a gargantuan 1325 mm on the XL. The medium frame comes in at 1244 mm. For reference, here’s the full geo chart:

These numbers, paired with its ample (and rearward-arcing) suspension should make the Dreadnought awfully capable when it comes to descending at speed, but don’t seem so extreme as to relegate it to pure bike park or shuttle duty.

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) We bet that the rear suspension of the Dreadnought, with its rearward axle path and progressive leverage curve, will feel great when it comes to mowing down rough terrain, but how much does it sacrifice when it comes to poppiness and the ability to gain speed by pumping the bike through rolling terrain?

(2) The chainstays on the larger sizes of the Dreadnought are quite long to begin with, and only get longer as the suspension cycles, due to the rearward axle path. Are they going to feel really long on the trail, or will the Dreadnought feel relatively normal in that regard? And what kind of stance and body positioning will it encourage?

(3) How versatile does the Dreadnought feel as a burly, long-travel Trail bike, and does the idler pulley induce enough drag or noise to be noticeable when climbing?

(4) Conversely, 154 mm isn’t a small amount of rear-wheel travel, but it’s also less than some of the burliest Enduro bikes on the market (e.g., the new Nukeproof Giga). So does the Dreadnought punch above its travel, owing to the rearward axle path?

Bottom Line (For Now)

The Forbidden Dreadnought looks like a highly capable Enduro bike, with some rather unique geometry touches and a high-pivot suspension layout that’s more commonly found on dedicated DH bikes. We’re very curious to find out how all that adds up as a package, and where it fits in among the class of long-travel, predominantly descending-oriented Enduro bikes that still offer respectable performance when the trail points back up hill. Blister Members can now check out our Flash Review of the Dreadnought, and stay tuned for a full review to come.

FULL REVIEW

The Dreadnought was one of the new bikes that I was most excited to get on this year, and after a few months on it, I’m ready to weigh in on how it performs on the trail, and how it stacks up to the rest of the market.

The Build

We got our test bike as a frameset and built it up with a spec that is largely similar to that of the stock XT build, but with a few key differences. Here are the highlights of our test bike build:

- Fork: EXT Era and RockShox ZEB Ultimate (170 mm)

- Shock: Fox Float X2 Performance Elite

- Brakes: Shimano XT 4-piston (203 mm rotors)

- Drivetrain: Shimano XT w/ XTR shifter

- Wheels: DT Swiss XM1501

- Tires: Hutchinson Griffus 2.5 (front) / Griffus 2.4 (rear),

- Dropper Post: PNW Components Rainier Gen 3 (200 mm)

Performance-wise, the biggest difference between our build and the stock XT option is the fork; both the EXT Era and RockShox ZEB Ultimate are perfectly appropriate choices for this sort of bike, but have their tradeoffs compared to the Fox 38 Performance Elite that comes stock. Check out our Trail / Enduro Fork Roundup for a whole lot more on that.

If I were building up a Dreadnought as my own ride, I’d probably opt for a slightly burlier wheelset than the DT XM1501 wheels that I ended up using, but they were what I had available at the time (it’s 2021, after all). I haven’t spent much time on the e*thirteen LG1 EN rims that Forbidden specs, but the DT 350 hubs they pair them with are excellent, and on paper the LG1 EN rims seem like the right class of rim for the Dreadnought.

Both of Forbidden’s stock builds (which you can read about in the First Look above) seem well chosen given the intentions of the bike. And kudos to Forbidden for specing a Double Down casing on the rear Maxxis Minion DHR II tire — it’s nice to see something beefier than an Exo or Exo+ on the rear of what is supposed to be a bruiser of an Enduro bike.

It’s worth noting that the Dreadnought requires more than one full-length chain, at least in the size Large that we’ve been testing. For our build, with a 10-51 tooth cassette and 34t chaining, I needed 132 total links — six more than Shimano includes with their standard-length chains. If you’re lucky, you might be able to snag a few spare links from your local shop if they have a remnant from a chain they installed on a conventional bike. Otherwise, one extra chain split up into extra pieces will get you through a whole lot of replacement chains. And bear in mind that the required chain length will vary significantly based on frame size, given the 14 mm variation in chainstay length from one size to the next.

Climbing

I’ve ridden a number of high-pivot Downhill bikes before, but the Dreadnought was my first time on an Enduro bike with such a layout. So, one of my biggest questions going into my time on the Dreadnought was to see just how much of a difference the high-pivot suspension and idler combo makes on the way up, particularly in terms of drag, traction, or other factors that I hadn’t even thought of.

First off, the pedalling position on the Dreadnought is quite good. As we noted in our First Look, the effective seat tube angle on the Dreadnought is not especially steep at 76° in all four sizes, but the actual seat tube angle ranges from 73 to 77.1°, getting steeper as the sizes grow larger. That means that the Large (76.1°) and XL (77°) frames have a steeper actual seat tube angle than effective.

A lot of bikes have an effective seat tube angle that sounds steep on paper, but by the time you raise the seat to a height that would actually be usable by someone riding one of the larger sizes, it’s slackened out dramatically due to the relatively slack actual seat tube angle. That’s not the case on the Dreadnought. The pedalling position feels natural and efficient, and it’s easy to stay centered on the bike and keep the front wheel planted on steeper climbs. If the Dreadnought were designed to work more on mellow, rolling terrain I might wish the seat tube was just a touch slacker, but given its design intentions, the seat tube angle feels perfect.

[And if you could use a refresher on what all that stuff about seat tube angles means, check out the section of our Mountain Bike Buyer’s Guide on the subject, starting at page 58.]

The Dreadnought is also fairly economical when it comes to suspension movement under pedalling input. As we’ve noted on a few versions of the 2021+ Fox Float X2 now, the shock’s climb switch isn’t especially firm, but the Dreadnought also doesn’t feel like it needs a ton of help in that regard. It’s definitely not the absolute firmest-pedalling ~155mm-travel bike we’ve been on recently — the Privateer 161 still wears that belt. But I’d place the Dreadnought a bit on the more efficient side of average, and it also does an uncommonly good job of both pedalling efficiently and remaining active during rougher sections of climbing. It is worth noting that I generally found myself running relatively firm compression damping settings on the Dreadnought to get the downhill performance that I wanted, and that almost certainly helped the cause on the way back up, too.

So how about the idler drag? There definitely is some, but it’s not as big a deal as I might have guessed, either. The more you’re simply grinding up a long fire road or similar, the less it matters. On steeper, more technical climbs, the slight loss of efficiency feels like a bigger deal. And that makes sense — if you’re cruising up a relatively mellow climb, a slight loss of efficiency might mean you work a touch harder or go slightly slower, but it’s not going to be make-or-break. If you’re on the ragged edge of being able to put down enough power to make it up a rough, steep section, that slight loss does start to mean something.

The difference in efficiency also feels a lot more obvious when you’re switching back and forth between the Dreadnought and another bike without an idler. If you’re riding a Dreadnought as your only bike, there’s a very good chance that you’ll just get used to the added drag and stop noticing it all together after a few rides. It’ll still be there, of course, but it will also feel normal. If you’re going back and forth between the Dreadnought and something with a conventional drivetrain, you’re more likely to notice a real difference.

It’s also worth noting that drivetrain cleanliness matters more on the Dreadnought than on bikes with a conventional drivetrain layout. If you keep things clean and the chain properly lubed, the difference between the Dreadnought and a more typical bike isn’t all that dramatic. Get lax about either, though, and the drag really starts to add up quickly. I do wonder how much of a problem this might become in really wet, muddy conditions, but it’s been an exceedingly dry summer here and I’ve unfortunately had no real way to find out.

All that said, the Dreadnought climbs just fine for a bike that is meant to be oriented much more toward aggressive descending than setting KOMs on the way back up — Forbidden calls it “a DH bike in all but the small print,” after all. There are certainly more sprightly ~155mm-travel bikes out there if that’s what you’re after, but as we’ll get into below, those generally can’t match the Dreadnought for stability and composure at speed once things really get moving.

Descending

Forbidden talks a very big game about the Dreadnought’s descending prowess, and based on my past experience on high-pivot Downhill bikes, I was very curious to see how the layout would work in a shorter-travel package.

First, the good parts: perhaps unsurprisingly, the Dreadnought is probably the best <160mm-travel bike I’ve ever ridden when it comes to just obliterating rough, high-speed, choppy sections. If you find yourself riding a lot of trails that are full of big braking bumps or fast sections full of exposed roots and the like, the Dreadnought is extremely smooth and composed in those scenarios. The high-pivot suspension definitely helps here, as does the fairly long wheelbase (1,284 mm on our size Large). Bump absorption is excellent, particularly as speeds increase. Small-bump sensitivity at lower speeds is solid, but the Dreadnought really comes into its own when there’s room to open up and charge. And it makes sense that the benefits of a high-pivot layout would be more apparent at speed — the idea is to let the rear wheel move back and up over obstacles, rather than getting hung up. The slower you’re going, the less need there is for the rear wheel to move rearward to get up and over a bump.

As for suspension setup, the Fox Float X2 rear shock shipped with no volume spacers installed. Fittingly, the Dreadnought is quite progressive overall (about 31% total progression), but much of that progression happens very deep in the travel. The leverage curve (which can be seen above) is much flatter through the midstroke, before ramping up aggressively deep in the travel. Given that, I experimented with both one and two volume spacers (the most Fox allows in this configuration of the Float X2), ultimately settling on one as my preferred setup.

This wasn’t a totally straightforward setup, though. As recommended by Forbidden, I started at about 35% sag with no volume spacers, but found myself bottoming out too regularly, and wanted more midstroke support out of the bike. Running higher pressure and bringing the sag as low as about 28% helped on both counts, but came at the expense of a fair bit of traction and small-bump sensitivity. One volume spacer and about 31-32% sag ended up being the sweet spot for me, but I still think I’d prefer a slightly straighter leverage curve, to help get a bit more midstroke support without needing to run the shock quite so firm overall. A coil shock might well help here, too — there’s plenty of total progression to run one, and a coil should offer better midstroke support. Forbidden does offer an EXT Storia rear shock for a $700 upcharge, or a Push ElevenSix for $800, but we unfortunately have not been able to try either on the Dreadnought.

I had a somewhat easier time with the damper setup, though as noted above, I did find myself running somewhat firmer compression settings than I might have expected. The high-speed rebound knob on the Float X2 is also fairly tricky to access on the Dreadnought, though that’s the case on a lot of bikes, due to the knob’s position just forward of the rear shock eyelet. I settled on six clicks for low-speed compression and four for high-speed (both counted from fully closed), give or take a click or two depending on the trail and conditions. I settled on running the high- and low-speed rebound six and 11 clicks from closed, respectively.

The handling of the Dreadnought gave me a bit more trouble though, and I think a lot of that comes down to just how long the rear end is — due to both the already-long chainstays, and the additional chainstay growth that occurs with the high-pivot layout. The 450 mm chainstays on our size Large test bike are long to begin with, but also grow by about 30 mm by bottom out. Most bikes with a conventional layout have just a few millimeters of rearward axle path early in the travel before the wheel comes back forward significantly. That makes for a huge difference between the Dreadnought and most other bikes once you get deeper into the travel, and it’s apparent on the trail.

This trait gave me the most trouble in mid-speed, well-supported corners where you’re substantially preloading the suspension and transferring weight to the rear wheel mid-way through the turn. The Dreadnought just feels long and ponderous in those situations. At 1,284 mm, its wheelbase is definitely on the long side, but it’s also far from being the longest bike I’ve ever ridden. Still, bringing the back end of the bike around in some situations takes a lot of very deliberate effort, and even after I’d spent a lot of time on it and gotten used to the sensation, the Dreadnought still felt more sluggish than I’d like.

The massive amount of anti-rise on the Dreadnought probably exacerbates that issue — if you absolutely nail your braking points it’s less noticeable, but the suspension compresses a whole lot when you get on the rear brake, and that only makes the rear end feel longer (because it is when the suspension is deeper in its travel) if you’re still feathering the rear brake a bit on the entry to a corner. And even if you’re doing a perfect job of braking early enough to get around issue, it still means that the suspension firms up dramatically when you are on the brakes. It’s an inherent limitation of a high-single-pivot layout with this much rearward travel, and is a big part of why a lot of other high-pivot Enduro bikes (including the Norco Range, Cannondale Jekyll, GT Force, and Kavenz VHP 16) have gone with a Horst-link layout, to reign the braking performance in a bit.

Popping off of smaller lips and rollers posed a similar issue: when you preload the suspension into a lip, the Dreadnought doesn’t rebound from that compression and offer the same pop that you’d expect from most bikes with similar suspension travel. The bigger the jumps got and the less I was needing to really seek a huge pop to pull for a gap, the more natural the Dreadnought felt, but popping over little holes and rollers is not its forte. The Dreadnought definitely prefers a more brute-force approach of simply steamrolling those kinds of features, and while it does that very well, taking a more active approach isn’t met with the kind of response you might hope for.

Or at least that’s all true on the size Large I’ve been riding. One of the things that I’ve been trying to get my head around when it comes to the Dreadnought is Forbidden’s approach to size-specific chainstay lengths. As we’ve written a lot about at Blister, we’re definitely on board with this concept in general — it stands to reason that, in order to make the balance of a bike consistent across a range of sizes, you need to lengthen the rear end as the front end grows longer. The question is, by what margin? Forbidden has opted to increase the chainstay length by a whopping 14 mm per size (more like 3–6 mm is typical). Their argument is that this makes for a consistent ratio of chainstay length to wheelbase on all four sizes, and the math checks out there. But is that really the right goal?

I’m honestly not sure. At least before you account for the chainstay growth due to the rearward axle path, the 422 mm stays on the size Small are about as short as things get these days, and I can’t think of a production bike with longer chainstays than the 464 mm behemoths on the XL Dreadnought. And of course, I can’t test multiple sizes of this (or most other) frames and give a meaningful comparison of how the chainstay length impacts the overall package, because the overall fit is going to impact my impressions of the bike far too much for it to be a real A-B test. I can’t swap a different size swingarm onto the Dreadnought to see what that does either, because all four sizes use the same one and vary the chainstay length by moving pivot locations on the front triangle. What I can say is that I’m pretty sure I’d like the Large Dreadnought better if the chainstays were just a little shorter. It’s definitely the right size for me overall, but it also feels ponderous and awkward a lot of the time when it’s not just pointed straight down something steep and rough, and I can’t say the same for some bikes with even longer wheelbases that I’ve recently ridden — including the Nicolai G1.

Even the new Trek Session — in the largest size R3, no less, with 452 mm chainstays and a 1,312 mm wheelbase — feels more balanced and easier to maneuver in tight spots than the Dreadnought. I think a lot of that is probably down to the fact that, while the Session also features a high-pivot layout, its axle path isn’t as rearward, and so in a lot of dynamic situations the rear end is actually going to be shorter than that of the Dreadnought; couple that with the fact that the Session has a longer wheelbase, and therefore a longer front-center makes for overall more balanced handling, even if the Session is even longer overall. Obviously, the Session is a dedicated Downhill bike and not a true competitor of the Dreadnought, but I bring this comparison up to illustrate that there’s more to consider than just static chainstay length, and that the balance between front- and rear-center is probably more important than either one in isolation.

I also think the Dreadnought would fit its intentions better with a bit more rear-wheel travel. Yes, it’s especially capable for a ~155mm-travel bike, but it’s also a bike that feels most at home going very fast and plowing through rough terrain in a straight line. There’s only so much that the high-pivot layout can do to disguise the fact that the Dreadnought doesn’t have a massive amount of rear-wheel travel, and in most other respects the Dreadnought really does feel like a mini-DH bike. I just think it would be a more harmonious package with slightly shorter stays and ~170 mm of travel (which, intriguingly, sounds a whole lot like the new Norco Range, at least on paper).

The overall fit and finish on the Dreadnought frame is excellent, though I’m also not a fan of the internal cable routing arrangement. The brake hose and derailleur housing go internally through the top tube, exit just forward of the seat tube, and then run through their respective seatstays before reemerging near the dropouts. The dropper cable housing runs through the downtube. While the portions of the routing through the swingarm are guided, the sections inside the front triangle aren’t, and this poses two problems. First is that it’s just a hassle to route them. There are bolt-on ports to open up somewhat wider openings, but getting both the brake hose and derailleur housing through the top tube, in particular, was a pain. Second, and perhaps more importantly, there’s a ton of rattling from those unguided lines inside the big, hollow tubes. Putting forth a bit of extra effort to route the lines in the first place is one thing; listening to them constantly rattling on the trail is another. There are of course steps that you can take to mitigate the issue, such as using foam housing dampers and the like, but that only further complicates installation and isn’t 100% effective.

I also had a few of the pivot bolts loosen after the first few rides. I cleaned everything up, applied a little blue thread locker, and they’ve since been solid. It wasn’t a big deal and I caught all of the loose bolts before they caused any real issues, but it’d be worth keeping an eye on for any Dreadnought owners.

Who’s It For?

In my mind, the Dreadnought makes the most sense for riders looking for a hard-hitting park bike that can still be pedalled to the tops of descents fairly regularly. It’s most at home going very fast in very rough terrain (particularly for a bike with ~155 mm of rear-wheel travel), but also favors trails with few awkward, tight sections so that you can keep the speeds consistently high. That said, I also think that a bit more suspension travel would be ideal for a truly dedicated park bike. And while the Dreadnought is plenty capable of earning its turns, the added drag from the idler, its awkwardness in tight spots, and the fact that it isn’t especially engaging at less than full throttle makes it a less than ideal everyday Trail bike for most people.

Bottom Line

Forbidden is onto something when they call the Dreadnought “a DH bike in all but the small print.” It’s an impressively stable and capable 154mm-travel bike, and its high-pivot suspension really does pay dividends when it comes to plowing over rough, chunky terrain. That high-pivot suspension and the bike’s very long chainstays also make for a bike that’s less agile at lower speeds, and harder to pump, pop, and throw around than its more conventional brethren. And so the Dreadnought feels a little bit caught in the middle. On one hand, it’s a bike that’s most at home going very fast over very rough terrain — and does that well — but it isn’t especially versatile when the speeds drop off. On the other hand, it’s got less suspension travel than most other bikes with a similar character, and despite the high-pivot layout, does feel like it at times. In the right circumstances, the Dreadnought is very good, but it also feels like the window in which it excels could be a lot wider with a few tweaks. As is, it’s a bit caught in the middle, unsure of what exactly it wants to be.

I owned the shorter travel Druid for around a year. rode great and It definitely punched above its travel numbers and pedaled well. The rearward axle path also did take some pop out of jumping, etc. My biggest caveat, and the reason I sold it, is I found the drivetrain to be very high maintenence with all the extra pulleys and bearings (top idler pulley and lower chain guide roller) with noticeable drag if I didn’t deep clean and relube the chain after every ride, and clean out the aforementioned upper and lower idlers/bearings every 4-5 rides. I do ride in the desert so perhaps this would not be as big a deal for those blessed with wetter climates…

Really, really like the seat tube angle per size changes. Ditto for the chainstay lengths, although they do seem long overal, I applaud the consistent size increases

So I have a druid, and while there is a hair more maintenance, my experience has been better than Robertsons. That said, i do live in the PNW. I also switched to the MRP SxG which got rid of most of the drag. Mine hasnt been noisy, but I know some folks not using HG+ drivetrains (fools that they are) have had some as the idler is designed for the HG+ chain. I think some folks have also had issues if their chainline isnt dialed. Given the short distance between the idler and the chainring, any misalignment is more noticeable. Suspension wise, its a beast. It also climbs fantastically. Not quite on par with a dw link on a fire road or other smoother surface until you pull the cheater switch, but on any kind of technical climbing the rearward axle path and the anti-squat inherent in HSP designs put it at the top of the pack. Its pretty cool to have high antisquat without the deadspot you get in some counter rotating link designs.

I have a Druid as well – any drivetrain or drag issues were negligible IMO. Wax lube has been my go to for a while now and its basically maintenance free, and is no different on the Druid. I’m wary of the Beta review of the Dreadnought. Guy was lubing the chain mid-ride and complaining about debris sticking to the chain. As others have noted on other forums, the Druid can be run without the lower roller guide at least on the L and XL models if you so desire.

Following up on the above comments. I found it interesting that the Beta Dreadnought review took place in the same Southern California environment as I owned my Druid. The ”soil” here is mostly decomposed granite that is very sticky. Even with other non HSP bikes I found on longer 20+ mile rides if my chain wasn’t freshly lubed it would get draggy/noisy over the course of the ride. This was definitely more noticeable in desert or more coastal trails as opposed to when I was in other areas or up in the mountains. This makes me suspect Beta’s Dreadnaught and my Druid issues are in large part due to the wonderfully terrible dirt we are blessed with down here…

Looking forward to hear more about this bike. At 6’6 I love what they have done to the STA and chainstays on the XL. It seems most bike companies forget about us tall guys when designing their bikes. I do ride a 170/170 while living on the shore and riding park 8-10 days per year…. So my biggest hesitation is losing that extra squish in the rear. Definitely curious if this bike punches above its weight like people say about the druid.

I’ve now spent a couple months getting used to my Dreadnought. I’m 6’5 riding an XL with a 180mm Zeb and an RS SuperDeluxe coil.

I came from a 2021 Commencal Meta AM in XL that I just never felt comfortable on. The meta with its 520 reach/433 chainstays constantly felt like I was correcting my weight fore & aft to weight the front correctly.

Dreadnought solves all those issues. The long chainstays are definitely a little harder to manual quickly on the trail, but you get used to it quickly. I can maintain a much more stable upright position and still feel like I have great grip on the front. I’d love a little more travel in the rear, but the 154 it has feels like significantly more. It feels so much better with the coil than the air though.