Fezzari La Sal Peak

Wheel Size: 29’’; compatible with 27.5” rear wheel

Travel: 170 mm rear / 170 mm front

Reviewer: 6′, 175 lb / 183 cm, 79.4 kg

Test Locations: Washington, British Columbia

Blister’s Measured Weight: 33.6 lb / 15.2 kg (as tested, see below)

Geometry highlights:

- Sizes offered: Small – XL

- Headtube angle: 64°

- Seat tube angle: 77.5°

- Reach: 485 mm (size Large, tested)

- Chainstay length: 437 mm (all sizes)

Frame material: Carbon Fiber

Price:

- Frameset w/ Fox 38 Factory fork and Float X2 shock: $3,899

- Complete bikes starting from $3,999 (see below for details)

Intro

Fezzari is a direct-to-consumer bike brand based out of Utah, and the La Sal Peak is their biggest offering — a 170mm-travel Enduro bike that they nevertheless tout as being “versatile” and at home on a range of trails. So how does the La Sal Peak slot into its very crowded category, and who’s it going to work best for? We’ve started spending time on the La Sal Peak, and Blister Members can check out our Flash Review now for our early on-trail impressions. But for the background on the frame design, build options, and all that info, let’s get right to it:

The Frame

The La Sal Peak gets 170 mm of rear-wheel travel from a 230 x 65 mm rear shock, by way of a Horst link layout. It’s offered in carbon fiber only and is designed around a matching 170mm-travel fork.

The feature set is fairly standard for a modern Enduro bike — it’s built around a 148 mm Boost rear wheel and a threaded bottom bracket shell, and uses fully guided internal cable routing. ISCG-05 tabs are included if you want to run a chainguide, as are molded rubber guards on the chainstay, seatstay, and underside of the downtube. There’s also room for a water bottle inside the front triangle on all sizes, and accommodations for a second on the underside of the downtube. Tire clearance is stated to be up to 2.6’’, and the La Sal Peak uses a SRAM UDH derailleur hanger.

Fit & Geometry

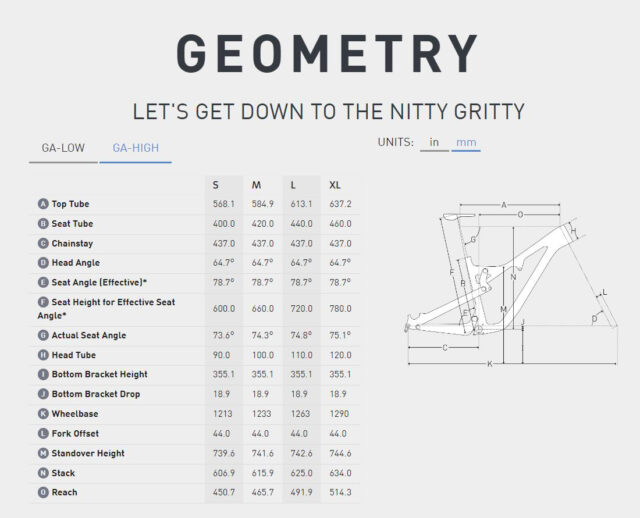

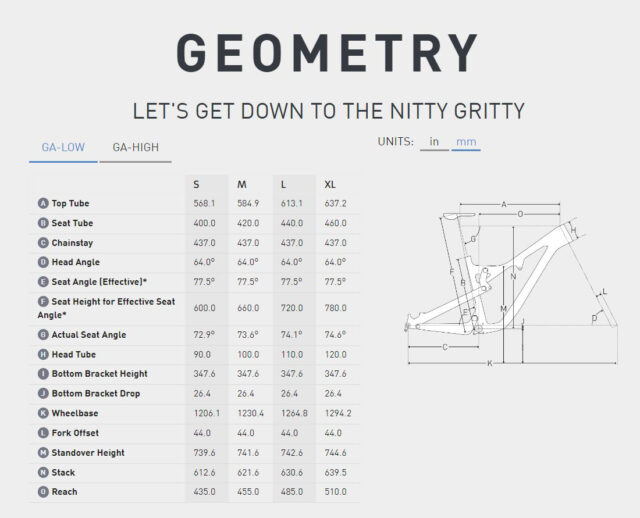

Fezzari offers the La Sal Peak in four sizes, ranging from Small through XL. All sizes get a 64° headtube angle, 77.5° effective seat tube angle, and 437 mm chainstays (in the low geometry position). Reach ranges from 435 mm to 510 mm (455 mm for the Medium and 485 mm for the Large). The high geometry position steepens the angles by 0.7°, adds about 10 mm to the reach (more in the smaller sizes and less in the bigger ones), and reduces the bottom bracket drop to 18.9 mm, from 26.4 mm.

The Builds

Fezzari offers five stock builds for the La Sal Peak, listed below, but all are customizable through the bike builder tool on their website. Drivetrain and brake configurations are set for a given build, but you can upgrade wheels, suspension, and the dropper post, as well as add optional extras such as tubeless setup, pedals, a chainguide, pre-installed frame protection, and so on.

- Drivetrain: SRAM NX

- Brakes: SRAM Code R w/ 180 mm rotors

- Fork: DVO Onyx D1

- Shock: DVO Topaz 2

- Wheels: WTB i30 rims w/ Bear Pawls hubs

- Dropper Post: PNW Components Rainier

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 200 mm rotors

- Fork: RockShox ZEB Ultimate

- Shock: RockShox Super Deluxe Ultimate

- Wheels: Stan’s Flow MK4

- Dropper Post: PNW Components Loam

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 200 mm rotors

- Fork: RockShox ZEB Ultimate

- Shock: RockShox Super Deluxe Ultimate

- Wheels: Enve AM30 w/ Industry Nine 1/1 Hubs

- Dropper Post: PNW Components Loam

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX AXS

- Brakes: SRAM Code RSC w/ 200 mm rotors

- Fork: RockShox ZEB Ultimate

- Shock: RockShox Super Deluxe Ultimate

- Wheels: DT Swiss EX 1700

- Dropper Post: PNW Components Loam

- Drivetrain: SRAM X01 AXS

- Brakes: TRP DH-R Evo w/ 203 mm rotors

- Fork: Fox 38 Factory

- Shock: Fox Float X2 Factory

- Wheels: Enve AM30 w/ Industry Nine 1/1 Hubs

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer Factory

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) The La Sal Peak looks like it should be a relatively versatile take on an Enduro bike — just how Fezzari describes it — but is that borne out on trail?

(2) And how hard can the La Sal Trail be pushed when things start getting steeper, rougher, and faster? Is it just versatile, or does it have the sort of top end that you’d hope for from a 170mm-travel Enduro bike, too?

Flash Review

Blister Members can read our Flash Review of the La Sal Peak for our initial on-trail impressions. Become a Blister Member now to check out this and all of our Flash Reviews, plus get exclusive deals and discounts on gear, and personalized gear recommendations from us.

Bottom Line (For Now)

The Fezzari La Sal Peak is a long-travel Enduro bike that’s meant to be more versatile than just a full-on gravity-fueled sled, and with a variety of customizable builds and solid pricing, it looks compelling on paper. We’ve been spending time on one and will have a full review coming soon.

FULL REVIEW

Intro

Enduro bikes have gotten longer, slacker, more stable, and grown in travel in recent years, but Fezzari talks a lot about their 170mm-travel La Sal Peak as being “versatile” for the category. Having now spent several months on the bike, they’ve certainly got a point — but that versatility also comes with tradeoffs elsewhere. So who is the La Sal Peak going to work best for, and who might be better off elsewhere? Let’s dive in.

Fit & Sizing

Fezzari’s geometry chart doesn’t list recommended height ranges for a given size, but the Large frame’s numbers looked to be right in my personal wheelhouse at 6’ / 183 cm tall, and as expected, I had an easy time getting comfortable on the Large La Sal Peak. As per usual for a modern Enduro bike with a fairly steep seat tube, the seated pedaling position is upright and the cockpit doesn’t feel terribly long (despite the roomy 485 mm reach), but the La Sal Peak is very much in line with the norm for the class of bikes.

Despite not having especially long chainstays (437 mm in all sizes) the La Sal Peak’s steep seat tube angle (77.5° effective, 74.1° actual) kept me nicely centered on the bike, even on very steep climbs, and I had enough insertion for me to run a 240 mm OneUp post with room to spare. I still find that much dropper stroke to be a little bit overkill most of the time, but it’s nice to have the option.

Mostly what stood out to me about the La Sal Peak from a fit perspective is that it feels squarely like an Enduro bike — not a more moderate Trail one — in terms of its fit and body positioning. Of course, we’re talking about a 170mm-travel bike here, so that’s probably not much of a surprise. But as we’ve said in a lot of instances, super steep seat tubes and the more compact cockpit that they produce make lots of sense on more winch-and-plummet oriented Enduro bikes, while moderating things a little bit tends to be a good call on bikes that are meant to be more versatile all-rounders. Given Fezzari’s description of the La Sal Peak as a versatile Enduro bike, it’s notable that the fit and body positioning hews more squarely to the Enduro end of things.

Climbing

The La Sal Peak’s pedaling efficiency is well above average for a 170mm-travel Enduro bike. As you’d expect given its travel, the La Sal Peak is still not a super sprightly feeling bike that encourages you to put down the hammer and climb really quickly, but if you’re more inclined to stay seated and grind your way up, the La Sal Peak does quite nicely.

The flip side of that efficiency is that the La Sal Peak gives up some traction under power, particularly compared to many of the less-efficient, more planted-feeling Enduro bikes out there. I think there are two reasons why: first, more efficient-pedaling bikes tend to give up some suspension sensitivity and traction under power in general. But on top of that, the La Sal Peak’s suspension feels notably firm off the top — under power or otherwise, as we’ll get into more in the “Descending” section. On the plus side, that initial firmness helps keep the rear suspension up in its travel when the trail’s pointed straight up and a lot of your weight is shifted rearward; it just also means that small-bump sensitivity isn’t the La Sal Peak’s strong suit. The more you prioritize efficiency over compliance and traction, the more appealing the La Sal Peak will be, but the tradeoff there is real. Suspension setup factors in there, of course, and as I’ll discuss more in the “Descending” section, I wound up preferring to run the rear suspension on the La Sal Peak quite firm — which definitely contributed to my impressions here. If you’re game to run a much softer, more cushy suspension setup it’s definitely possible to get more traction and compliance out of the La Sal Peak, but I wouldn’t call it the bike’s strong suit in general.

As I alluded to in the Fit & Sizing section, above, the La Sal Peak’s steep seat tube and overall body positioning feel oriented somewhat more toward staying seated and grinding up extended climbs, rather than being especially quick and easy to move in / out of the saddle on more rolling, varied terrain. For a big Enduro bike, I’m all for that decision; for a more all-rounder Trail bike, ultra-steep seat tube angles can make the bike feel more awkward to pedal when seated on flat ground, and put the seat more in the way when you’re standing off it to make a hard effort through a section of technical climbing. The La Sal Peak feels much more like an Enduro bike that’s hung onto a little more versatility than most, rather than a super long-travel Trail bike or anything like that, but with that goal in mind, it’s nicely sorted.

For what it is, the La Sal Peak also does a nice job of not being unduly cumbersome in tight spots and more technical climbing. It’s still a fairly long bike, overall (1,265 mm wheelbase for our size Large) and if true technical climbing prowess is a top priority, we’d definitely recommend a shorter-travel, more compact bike in general. But as far as 170mm-travel Enduro bikes go, the La Sal Peak is indeed less of a handful than most — especially in the “high” geometry position. Though as we’ll get into in a minute, I generally preferred the “low” one overall, for descending performance. So on that note:

Descending

So far, the La Sal Peak is living up to its billing — it feels like a big Enduro bike first and foremost, but is more efficient and a little quicker handling at mellow climbing speeds than most bikes in its travel class — but how would that shake out when the trail pointed back down?

In some respects, the La Sal Peak does feel notably versatile for a 170mm-travel Enduro bike, primarily in that it’s a little easier to handle in tight spots at low speeds than many of its competitors. Some other bikes that I’d also say that about — the Orbea Rallon (which, granted, has a little less rear travel) being high on the list — pull that off by feeling especially light on their feet, so to speak, and being really easy to pick up off smaller features and otherwise move around as needed. The La Sal Peak feels more planted and less lively than something like the Rallon, but is just a little more compact and less ponderous at low speeds than a lot of the longest, slackest Enduro bikes out there.

But to be honest, the La Sal Peak started to give me more trouble as the speeds picked up and I started pushing it harder. There’s definitely more than one way to make an Enduro bike that encourages fast, aggressive riding; being ultra-stable and planted (e.g. the Norco Range) is one option, but I’ve also gotten along really well with certain bikes that give up some stability in exchange for being sharp handling, and work well when being pushed hard, not so much by bulldozing everything in their path, but rather by facilitating precise, dynamic riding and exacting line choice.

And, frankly, I struggled to get the La Sal Peak to do either all that well. I think the suspension performance is one piece of the puzzle — I struggled to find a setup that balanced midstroke support without compromising small-bump sensitivity quite substantially. Fezzari doesn’t publish a leverage curve for the La Sal Peak, but it feels like there’s a significant digressive portion of the curve early in the travel, with the suspension feeling very firm off the top before giving way to a much softer region through the middle portion of the travel, and then ramping back up substantially after that. Small-bump sensitivity and midstroke support certainly tend to come as tradeoffs to some extent when it comes to setup, but the contrast felt especially stark on the La Sal Peak, and I struggled to find a setup that was all that good at either.

For my preferences, the best balance was to run the suspension fairly linear (i.e., no volume spacers in the rear shock) and quite firm to get the midstroke support I wanted when I started going faster and hitting things harder, and just live with the small-bump sensitivity being less than stellar. That’s a tradeoff that I end up making on quite a few bikes, to be sure, but it feels like more of a tradeoff on the La Sal Peak than most.

The upshot was that I had a hard time finding a balance where I wasn’t running very little sag, and therefore upsetting the dynamic geometry of the bike in that way, while also not blowing through the middle part of the travel on mid-size hits, especially on faster, rougher sections of trail, and thus having the La Sal Peak’s chassis feel unbalanced and unstable in the other direction. I do think that a coil shock (which I, unfortunately, wasn’t able to try on the La Sal Peak) would likely help somewhat, and I also think that folks who are more inclined to run their suspension comparatively soft and compliant are likely to have an easier time as well.

As I’ve written about a lot on Blister, a lot of my favorite home trails trend very steep, and I wind up preferring forks with a lot of midstroke support and a fairly firm setup to keep the front end from diving on those sorts of steep trails. Running a fork with that kind of setup definitely made finding a balance between front and rear suspension settings on the La Sal Peak harder; if I softened both ends up and aimed for a more plush, compliant ride over a firm, supportive one, the bike did feel more balanced, but also gave up stability and composure, particularly when plowing through rougher sections at speed. And so I think that comes back to where the La Sal Peak does (and doesn’t) work especially well. The more you’re after a very long-travel bike because you want the extra compliance and plushness; want a bike that still pedals reasonably well; and are happy to trade off some composure when pushing the bike hard on burly trails for all of that, it does make some sense — especially when you account for the value of the build kits (more on that in a minute).

The La Sal Peak’s frame also doesn’t feel very stiff torsionally, especially in the front triangle, and I think that played a role in the La Sal Peak feeling less precise and sharp handling than I’d hoped for, particularly at higher speeds and when I was pushing the bike harder. That imprecision wasn’t particularly noticeable on mellower trails or at lower speeds, but especially when trying to go fast in rougher terrain, I found myself needing to really stay on my toes and make more last-second line corrections on the La Sal Peak. I could work with it and still go pretty hard on the La Sal Peak if I brought my A-game, but it didn’t inspire the kind of confidence to push things that you’d hope for from a 170mm-travel Enduro bike.

The Build

I tested the La Sal Peak with a non-standard build, so there’s not too much to say here. Our review bike had a SRAM GX drivetrain, TRP DH-R Evo brakes (full review coming soon), Reserve 30|HD wheels, and RockShox Super Deluxe Ultimate (2022 model) and ZEB Ultimate (2023 version) suspension. The closest stock build from Fezzari would be La Sal Peak Elite Race (which subs in Enve AM30 wheels, SRAM Code RSC brakes, and the 2022 model-year version of the ZEB) for a very respectable $6,000 all in. It’s a sensible spec given the intentions of the bike and a notably good value for money.

That value makes tying a bow on this review harder. Because while I didn’t love the ride quality of the frame in some respects, my initial instinct was always to compare the La Sal Peak to other bikes that I’d been on with relatively similar builds — which in many cases cost thousands more. Assessing the La Sal Peak’s limitations gets trickier when you take that price into account. For just a few hundred dollars more than the entry-level Santa Cruz Megatower R (which comes with a base RockShox ZEB R and Super Deluxe Select shock, a SRAM NX drivetrain, and relatively weak SRAM G2 RE brakes), Fezzari gets you the top-tier RockShox suspension package, a better drivetrain, better brakes, and Enve carbon wheels.

Comparisons

The fit and low-speed handling of the Firebird is very reminiscent of the La Sal Peak, but they feel much more different once you start going faster and pushing them harder. The Firebird both has better small-bump sensitivity and its rear suspension feels more supportive and composed on larger hits. The two have some similarities in that they’re sort of middle-of-the-road in terms of stability for a 160+ travel Enduro bike, but the Firebird feels much quicker and sharper handling than the La Sal Peak, and therefore easier to ride precisely when pushing hard.

In the La Sal Peak’s favor, it’s the more efficient pedaler of the two and is a substantially better value in terms of build spec. But the Firebird is more capable and confidence-inspiring when you start pushing it harder.

When I was talking about Enduro bikes that aren’t mega stable but can still be ridden very hard because of how well they facilitate very precise, dynamic riding, the Rallon was the primary example I had in mind. Both the Rallon and the La Sal Peak pedal very well for how much travel they have and give up a substantial amount of small-bump sensitivity to get there, but the Rallon is much sharper handling and more lively and energetic feeling than the La Sal Peak. The La Sal Peak is a little bit more stable and planted feeling, but as with the Firebird, I had a much easier time going hard on the Rallon because of how much more precise its handling is, which allowed me to make up for the Rallon’s more modest stability and composure by being bang on the ideal line, so long as I brought my A-game.

The Privateer 161 is a bit like a more stable, game-on version of the Rallon — both pedal extremely well, and are quick handling and precise for their level of stability; the 161 is just a step up from the Rallon. That makes the 161 both more stable at speed and more precise in its handling than the La Sal Peak, but it also takes a more aggressive approach to come alive and doesn’t feel nearly as versatile.

The Capra reminds me of the La Sal Peak in terms of its fit and body positioning quite a bit, but is more plush and cushy in terms of its suspension performance, and less efficient under power. The Capra stands out most for its ability to feel relatively easy-going (by the standards of 165+ mm travel Enduro bikes) while also holding up to being pushed much harder when called upon. The La Sal Peak is a far more efficient pedaler, but doesn’t inspire as much confidence when the descents get steep and speeds pick up.

Very similar story to the Capra — the Gnarvana is a little more stable and correspondingly less nimble than the Capra, but they’re a good comparison for each other overall. The Gnarvana isn’t as efficient as the La Sal Peak (though by a smaller margin than the Capra), but it’s also more stable at speed and its suspension feels much more composed and forgiving, both in terms of small-bump sensitivity and midstroke support.

The VHP 16 is another example of an Enduro bike that doesn’t need a wild amount of speed or aggression to come alive, but can still be pushed fairly hard, too. The VHP 16 is more nimble and precise than the La Sal Peak at moderate speeds and up, and has much better suspension performance, especially in terms of small-bump sensitivity and midstroke support. And while the VHP 16 isn’t ultra-stable by the standards of 160+mm-travel Enduro bikes, its outstanding suspension performance and more precise handling make it the easier bike to ride fast and aggressively. Both pedal notably well, though the La Sal Peak probably has a slight edge there.

Super different. The Range is still our high-water mark for the most planted, stable, game-on Enduro bike out there, but it’s also an inefficient pedaler and notably un-versatile. If you want the nearest approximation of a true DH bike that you can still pedal to the top, the Range is outstanding, but it’s going to be overkill and unduly inefficient for most folks. The La Sal Peak is much more efficient and versatile, but far less composed and capable when it comes to going flat out on fast, rough, technical descents.

The Jekyll is also much more game-on and stable than the La Sal Peak, just by a bit smaller margin than the Range. Like the La Sal Peak (and in contrast to the Range), the Jekyll pedals fairly well, but the La Sal Peak can’t match the Jekyll for either small-bump sensitivity or midstroke support, and is a little bit quicker handling but substantially less stable at speed. The La Sal Peak is going to be more versatile as a long-travel Trail bike, with the Jekyll being a harder-charging bike when given the room to do so.

The new Megatower is also more bike than the La Sal Peak, in that it’s more stable at speed, less nimble when you’re going slower, and more planted and composed but less efficient in terms of its suspension performance. As with the Jekyll, the La Sal Peak is probably more versatile if you want a 170mm-travel bike that isn’t just focused on winch-and-plummet type trails, but the Megatower is more composed and confidence-inspiring when you start pushing it harder.

Who’s It For?

The La Sal Peak looks super promising on paper — it’s a great value for money as far as the parts spec goes, and the geometry seems like a promising take on an Enduro bike that holds onto some Trail bike versatility, just how Fezzari describes the La Sal Peak. The reality is a bit trickier. The La Sal Peak is definitely versatile in some respects — especially when it comes to pedaling efficiency — but its suspension performance left a bit to be desired and its handling was neither especially stable and composed, nor particularly quick and precise once the speeds picked up and I started pushing it harder. The La Sal Peak makes the most sense for folks looking for a long-travel bike that pedals well, who are interested in running a very soft, compliant suspension setup, and who are willing to forgo a substantial amount support to get there, but it feels like a bike that’s more compromised than it needs to be to achieve its goal of versatility.

Bottom Line

The Fezzari La Sal Peak is undeniably good value for money in terms of its parts spec and is quite efficient under power for a 170mm-travel Enduro bike while being comparatively easy to maneuver in tighter spots at lower speeds. That’s potentially a good recipe for folks who are interested in a very long-travel Trail bike of sorts, but the La Sal Peak’s lackluster suspension performance and vague handling at speed make it less appealing as a true game-on Enduro bike relative to most modern bikes in that class.

Damn. That’s a good review and comparison. Thanks. Happy Chad

Great review, and probably the best (inadvertent) attempt at Blister Spectrums for bikes that I’ve seen yet… and that the industry so sorely needs (instead of reviews that don’t do comparisons and can’t possibly do anything to help you choose your bike). Any thoughts about where the Privateer, Gnarvana, Firebird and Megatower sit in terms of composure, stability, precision and liveliness?

Great review. I’ve been riding my La Sal Peak for 6 months now pretty hard in western CO/Moab area. RS Zeb Ult. and Vivid Ult. for suspension. I thought I noticed a similar thing with the suspension, but kept wondered if it was just me, and I’m still trying to find a solution. If I’m hammering hard, particularly on repeated rocky drops, I have a sensation of getting “bucked” by the rear wheel, most notably on the take-offs. That would make sense if the suspension kinematics are firmer in the top portion of travel. Same thing if I come in hot to a rock garden–the rear gives me a bit of a bucking sensation upon initial contact before it settles down further into the rock garden. I don’t know if that’s the sensation you were describing, but it left me feeling a bit more squirrely than expected on trails/features I’m usually very familiar with. Does that echo your experience in some way?