2021 Pivot Switchblade

Test Location: Crested Butte, Gunnison, & Front Range, Colorado

Test Duration (so far): a few dozen miles

Size Tested: Medium

Build Overview (Team XTR 29”, as tested):

- Drivetrain: Shimano XTR

- Brakes: Shimano XTR

- Fork: Fox Factory 36 GRIP2

- Shock: Fox Factory DPX2

- Wheelset: Reynolds Black Label Wide Trail 349 + i9 Hydra hubs

Wheel Size: 29” (test bike), 27.5”+ compatible

Travel: 142 mm rear / 160 mm front

Blister’s Measured Weight (as built, w/o pedals): 29.2 lbs / 13.24 kg

MSRP: $5,499–$12,399 ($8,999 as tested)

Reviewer: 5’10”, 180 lbs / 178 cm, 81.6 kg

[Note: Our review was conducted on the model-year 2020 Switchblade, which is the same as the 2021 model.]

Intro

Four short years ago, in what now seems like another age in the bike industry, Pivot Cycles released a versatile All-Mountain bike called the Switchblade. In the bike archive of Pivot’s website (which is awesome; other bike companies take note), the tag line for the V1 Switchblade reads: “one bike, any trail.”

Now, Pivot is far from the only brand to tout their 130-145mm-travel bike as the ideal one-bike quiver. Being fair to Pivot, that’s a business necessity more than anything, since this category of bike arguably drives the mountain bike market. Look at it this way: if a bike brand is a US college athletic department, Trail / All-Mountain bikes are the football program. And as our reviewer Noah Bodman wrote in 2017 about the original bike, aside from the playfulness and progressivity of the V1 Switchblade, Pivot didn’t exactly build a class-leader. Without re-hashing too much of my colleague’s review, he used words like “harsh” and phrases like “isn’t setting any records for pedaling efficiency.” Not exactly what you want to hear about what many would argue is a brand’s flagship bike.

Fortunately, in mountain bike terms, four years is a different age, and Pivot has completely reworked and reimagined their do-it-all bike, resulting in the “V2,” 2020 Switchblade, which returns unchanged for 2021. Pivot hypes up this newest version using language similar to the V1 Switchblade, saying, “from bike park flow trails to raw backcountry routes, the Switchblade amplifies every rider’s skills and excels on any trail.”

With that versatility and all-trail mantra in mind, three of us spent time on the Switchblade, and well all chime in for the full review below. We’ll first discuss the design of the new bike and our initial impressions, and then see how those changed and evolved after about four months of riding the bike on a variety of trails.

The Frame

“Switchblade” isn’t a new name in the Chris Cocalis (Pivot Cycles CEO) bike universe. Though Pivot first used the name in 2016 for the V1 bike, Cocalis’s former bike company, Titus, used the Switchblade moniker for its own versatile, jack-of-all-trades bike way back in the early 2000s. But other than the name, the new V2 Switchblade doesn’t really resemble its ancestors.

The curvy top tube and down tubes that characterized middle-2010s Pivot frames (and a few Titus frames) are gone, apart from a kink in the down tube to accommodate the rear shock. This revised design aesthetics were seen on earlier Pivot releases, like the Firebird 29 and Mach 4 SL. And though some of the older, curvier tubes remain in their lineup, Pivot is doing a good job of translating their newer design style across their lineup. Speaking subjectively, I think it’s a much cleaner look.

But apart from aesthetics, those straighter tubes also have a performance benefit. The Hollow Core Carbon that Pivot uses in the new Switchblade frame design loses some weight in comparison to the older design. And without knowing the details of Pivot’s Hollow Core Carbon layup secrets, I’d have to imagine that those straighter lines also improve / simplify manufacturing processes, too.

Second, and most notably, the new Switchblade has a vertical, trunnion-mount shock. This is again, not a completely new thing for Pivot. The new Mach 4 SL also has a vertical-shock layout and it seems Pivot wants to include this design feature where it makes sense on their newer bikes. Pivot says that a vertical shock orientation yields a frame that is, among other things, lighter, stiffer, and uses less material.

This is a welcome change in my view. I’ve experienced some issues with the Fox DPX2 on my personal bike — a Yeti SB5.5 — which features a horizontal shock placement. Though I can’t find a ton of fault in the general performance of the DPX2, I have blown the damper (twice) under relatively benign riding conditions. It seems that side-loading during compression can be a problem for the Fox DPX2 on some bikes. Vertically oriented, trunnion-mounted shocks are said to be less susceptible to side-loading, and any shock mount and frame placement that promises to reduce side-loading has my approval.

Another positive aspect of the vertical shock layout, Pivot says, is a more progressive rear suspension, allowing for more voluminous air shocks or even a coil shock. Pivot confirmed that they had tested the Switchblade with other rear shocks, including coil shocks, through the course of design and testing. Looking up the four-digit code on the Fox DPX2 that came on our test bike shows that its stock tune on the Switchblade comes with a pretty large 0.6-inch volume reducer. This seems to back up Pivot’s claim of a more progressive rate. And as you’ll read later, my early ride impressions back up what Pivot is saying. But whether that suspension progression is solely attributable to the shock by itself or the shock and the linkage, I’m not sure. Pivot isn’t releasing leverage, anti-squat, anti-rise, or any other suspension kinematic information to the public, preferring to keep the secret in the sauce of their bikes’ ride qualities.

The new Switchblade’s vertical shock orientation also has the benefit of more easily fitting a full-size water bottle inside the front triangle. While being able to fit a bottle anywhere inside the front triangle is nice, it’s also nice to have that bottle easily accessible. On bikes where the shock is above the water bottle mount, I haven’t been as impressed by having a bottle on the bike since they can be tricky to get to. But on the Switchblade, the water bottle is higher and in front of the shock, making drinking on the go much easier. This adds to the convenience of not having water on your person.

Some things that didn’t change on the new Switchblade are Pivot’s commitment to the Superboost Plus standard (157 mm rear hub), their focus on designing each frame size individually, and the ability to run 29” or 27.5” wheels and tires. In our online world where no good deed goes unpunished by the comments section, Super Boost Plus seems to be enjoying some moderate acceptance, with some liking the increased stiffness while others, understandably, don’t love the idea of needing to get parts for a different standard. (Pivot makes a point to note the Super Boost hubs from DT Swiss and Industry Nine on Pivot’s stock builds, while mentioning that Onyx and Stans also have Superboost Plus standards available.)

Personally speaking, I’m coming around to Superboost Plus as a standard. The reasoning Pivot provides on their website is pretty sound from a structural perspective, claiming a 30% lateral stiffness gain over a “normal” Boost (148 mm) wheel. They also claim that a Superboost Plus rear wheel has the same lateral stiffness as a front wheel that is “normal” Boost (110 mm), better balancing the strength and stiffness from front to rear.

Pivot says they construct their frames to be different between sizes. Which is to say, their approach to sizing is more nuanced than simply shrinking or enlarging a given measurement to create a different-size frame. Pivot makes it a point to claim that a size Small of a given bike model is designed separately than a size Medium, and so on. The carbon layup itself and resulting tube diameters are unique to each specific size. The idea is that they can make the ride qualities of the frame the same for all sizes of frames for the riders they’re likely to have on board.

While that all sounds sensible, this is where I’ll piggyback on something that fellow Blister reviewer, David Golay, mentioned in his review of the BTR Ranger. Looking at the geometry charts of the new Switchblade, the rear chainstay measurement is the same 431 mm for all sizes from Extra Small to Extra Large. Granted, there are many variables that go into the linkage design and suspension kinematics, and to be fair to Pivot, same-sized swingarms within the size range of a bike model is mostly standard practice in the industry. But some companies are admitting that different-size rear swingarms for different-size bikes are indeed an issue worth addressing, since in most cases, the rear-center stays the same across sizes while the front-center is quite different. Building bikes with different rear-center measurements to balance ride characteristics across the size range doesn’t seem too far-fetched, does it?

The Superboost Plus spacing and a Flip-chip in the upper linkage mount allow the Switchblade to use 29” or 27.5”+ wheels, or even a 29” front / 27.5” rear “reverse mullet” setup (or just “mullet,” depending on who you ask). Tire clearance is generous, allowing for up to 29” x 2.6” or 27.5” x 2.8” rubber inside the rear swing arm. I’ll touch on the Flip-chip itself in the geometry section.

The new Switchblade continues Pivot’s long-time use of a modified four-bar linkage called DW-link. If you didn’t know already, “DW” stands for Dave Weagle, the creator of the linkage resulting from his research on suspension bob. How did I know that last part about Weagle’s research on pedal bob? Wikipedia. Yep, DW-link has a Wikipedia page. Oh the times in which we live. DW-link is by now a well-known suspension design in the mountain biking world and Pivot’s continued licensing of the link shouldn’t be particularly noteworthy, other than them sticking with what works.

The new Switchblade, as is standard for most high-end carbon bikes, has internal cable routing and cable ports that seal the frame from the elements. The cable port covers themselves are secured by a fastener, which is a nice touch that would indicate a greater amount of security and lack of movement from the cables inside their mounts.

Pivot offers a ten-year limited warranty on all of their new bikes (sold after Jan 1, 2017) from the date of purchase for the original owner. In a departure from the warranty information from many other brands, the warranty section of Pivot’s website is relatively detailed, even going so far as to include a FAQ area. It seems Pivot doesn’t want their customers making a warranty claim and then being surprised by the results, whether positive or negative. If you’ve ever made a warranty claim on a mountain bike, you’ll recognize that removing ambiguity is a good thing.

The Builds

Apart from the frame-only option, the new Switchblade comes in three general build levels: Race, Pro, and Team (listed from least to most expensive). These vary from $5,499 all the way up to $12,399, with lower-budget builds not really being available. The overall naming convention of the builds themselves can be a bit confusing, made even more so by the additional options / variables that Pivot offers within each build level. I’ll try and break it down as simply as I can…

The first choice is the drivetrain. Each build level (again, Race, Pro, and Team) can be ordered with an option from SRAM or Shimano. For instance, a “Race” level build can be ordered with a SRAM X01 groupset or Shimano XT groupset.

Then, you can decide on whether you want Fox Live Valve on your build. Without delving too deeply, Fox Live Valve is a constantly functioning, electronic control of your bike’s suspension; you can read more about it in our review of the Pivot Mach 5.5. The new Switchblade is set up to work with Live Valve and it can be spec’d only on Pro and Team builds.

Seems simple enough, but not so much. Inside the builds themselves, there are some anomalies. E.g., on the Race X01 build, the shifters, cassette (SRAM 1275), and chain are SRAM GX-level components and only the rear derailleur is SRAM X01. Similar story on the Race XT build, with several Shimano SLX level components included in that build, apart from the derailleur.

As for stopping power, every build comes with some form of 4-piston brakes, but again, there’s a good deal of variety. The Race XT actually comes with SLX brakes, the Race X01 comes with Guide RE’s, the Pro XT/XTR build gets you XT brakes, the Pro X01 comes with the G2 RSC, Team XTR comes with XTRs, and the Team XX1 AXS comes with G2 Ultimates. Simple, right?

From a suspension perspective, all non-Live-Valve builds feature a 44mm-offset Fox 36 fork and a Fox DPX2 shock. The Race-level builds have Fox’s Performance 36 (GRIP damper) and Performance DPX2, while all other builds have the Fox Factory kit, with the Factory 36 forks coming with Fox’s GRIP2 damper.

Race builds come with a Fox Performance Transfer dropper, Pro builds and Team XTR builds get a Fox Factory Transfer, and Team XX1 AXS builds get you a Rock Shox Reverb AXS wireless dropper. Dropper travel ranges from 100 mm on an Extra Small to 175 mm on size Medium and above, with exact travel depending on whether you’re on a Transfer or a Reverb.

As I said earlier, the Switchblade is capable of running a pair of 29” tires, 27.5”+ tires, or even a 29” front / 27.5” rear combo. Currently, only the 29” builds are shown on their site. But as we’ve just demonstrated, when you take into account the choices of drivetrain, brakes, Fox Live Valve or no Fox Live Valve, and 29er vs. 27.5+ vs. mullet … there are lots of combinations of builds available to consumers.

Mercifully for this reviewer, Pivot kept it simple with tires. Every build comes with a Maxxis Minion DHF 29”x2.5” Wide Trail with the MaxxTerra 3C compound and Exo+ casing on the front, and a Maxxis Minion DHR II 29”x2.4” Wide Trail with the same compound and casing on the rear.

This is where I stop diving into the minutiae of the individual builds and remind you, dear reader, to do your research when it comes to ordering your new bike. The naming convention of Pivot’s build kits isn’t misleading per se’, but it isn’t simple either. It’s worth reading the fine print.

So, with all that said, we’ve been testing the Team XTR build, which retails for a hefty $8,999. Our test bike came with Reynolds carbon, 34mm-internal-width Black Label Wide Trail 349 rims laced to Industry Nine Hydra hubs. They look great and we’ve already said nice things about those hubs. Problem is, that’s not the wheelset that is on Pivot’s website for the Team XTR build. They’ve subbed in the DT Swiss XMC1501 with DT Swiss 240 hubs and 36-tooth Star Ratchet. We’ll ask Pivot the details on this and get back with you.

Aside from the wheelset, the Team XTR bike we’ve been riding is standard, with the highlights listed below for our size Medium:

- Drivetrain: Shimano XTR (derailleur, shifter, & cassette)

- Brakes: Shimano XTR M9120 4-piston

- Fork: Fox Factory 36, GRIP2 damper

- Shock: Fox Factory DPX2

- Front Tire: Maxxis Minion DHF, 2.5”, EXO+ casing, 3C Maxterra compound

- Rear Tire: Maxxis Minion DHR II, 2.4”, EXO+ casing, 3C Maxterra compound

- Dropper Post: Fox Transfer Factory, 175 mm

- Crankset: Race Face Next R 32-tooth

- Handlebar: Pivot Phoenix Team Low Rise Carbon, 780 mm

- Rotors: Shimano XTR, 203 mm front / 180 mm rear

The Geometry

Long story short, Pivot isn’t entering the geometry wars with its new Switchblade. It’s rare that we review a bike and don’t write that the new model is longer and slacker. And the new Switchblade is no doubt longer and slacker than its predecessor — but it’s a smaller change in geometry than you might guess, given industry trends. And that more pragmatic approach is demonstrated in how Pivot is choosing to position their bike both within their own lineup, and in the market at large.

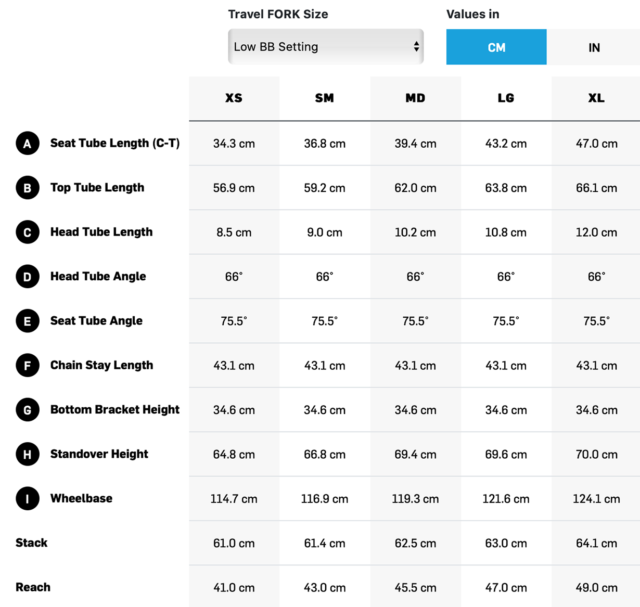

For a size Medium, with 142 mm of rear travel and a 160mm-travel fork, Pivot seems to be positioning their bike solidly in the middle ground between “Trail” and “Enduro.” But with the Switchblade, it’s not just travel that potential buyers should be focusing on. When the Switchblade’s flip chip (more on this later) is in its low setting, the head angle is 66° and the effective seat tube angle is 75.5°. Looking at reach, a size Medium is 455 mm, and the wheelbase is 1193 mm.

After that cursory glance, it’s not entirely clear to me where exactly the Switchblade slots into the mid-travel mountain bike world except to say, lots of places. In particular, it’s not nearly as long as some other bikes in its travel range. For example, two benchmark comparison bikes for the new Switchblade are Yeti’s SB130 Lunch Ride and Santa Cruz’s Hightower. Those bikes both have seat tube angles that are a degree steeper, head tube angles that are about degree slacker, and wheelbases that are 15-18 mm longer. And looking outside of those two particular comparisons, there are significantly longer and slacker ~140mm-travel bikes out there.

But Pivot, on its website, lists the Switchblade under the “Enduro” tab. Wait, what? Aren’t modern Enduro bikes just mini-DH sleds with super long wheelbases, and long reach, and long … everything? With the Switchblade at least, Pivot says no. And in this reviewer’s opinion, that is a solid move. Pivot already has dedicated DH bikes (Phoenix 29 and Phoenix V2), and longer-travel Enduro sleds (Firebird 29 and Mach 6). Pivot’s positioning of the Switchblade seems considerably more nuanced than merely taking its geometry or travel numbers and slotting it against obvious competitors. Now, you may not agree with the market-research exercise we’ve just undertaken. But providing context to a new bike’s geometry can be extremely valuable once we start parsing out the ride characteristics of a new bike.

Another notable geometry feature of the new Switchblade is the inclusion of a flip-chip where the seatstay meets the upper shock linkage, something we see on many bikes these days. On the Switchblade, this allows the head tube angle and seat tube angle to be steepened or slackened by a half degree. The bottom bracket height also goes from 346 mm in the Low setting to 352 mm in the High setting, and the reach goes from 455 mm in the Low setting to 460 mm in the High setting. As previously mentioned, the flip-chip also allows flexibility with wheel and tire size, and allows riders to dial in their preferred ride characteristics with a bit finer detail.

Initial On-Trail Impressions

I’ve now got a handful of rides and a few dozen miles on the Switchblade, and while we’ll post a long-term update in the future, I have some initial thoughts.

So far the Switchblade is fulfilling its mantra of versatility. I haven’t really found a time or place on any of my rides where it was clearly lacking compared to other bikes in its travel category. In fact, there are some areas where the new Switchblade is downright surprising (in a good way).

Most of those surprises come from a climbing perspective. I’ve climbed a long fire road to get to a backcountry route on the Front Range multiple times on the Switchblade and it was very efficient. I’ve also taken it on some shorter, very technical climbs and found myself out of the saddle and powering up and through sections where I’ve really had to muscle other bikes in this travel category. The new Switchblade is a very supportive and efficient climber. Notice I didn’t write, “for what it is.” In my opinion, the new Switchblade is a good climber. Full stop. I don’t expect that this particular impression will change much as I get more time with this machine.

Flatter and “up-and-down” trails have also left me appreciating the Switchblade’s overall design. Its suspension is very supportive and pedaling effort results in greater forward momentum than I’m accustomed to from a bike in this bike category. Its ability to maintain momentum and its progressive and supportive suspension creates a sensation that the Switchblade is extremely light on its feet. Some would simply call it “poppy,” but I think that might be oversimplifying things. To me, it feels more like the Switchblade is balanced and ready for rider input, rather than being ready to jib all over the trail. It is not a jibby Trail bike that feels inclined to boost off any and all features. But thus far, the new Switchblade does feel like less of a “big bike” than I expected.

On the downs, the Switchblade’s supportive and progressive suspension qualities have some competing interests. Out-of-saddle sprinting between features is excellent. I find myself enjoying the pedaling ability of the new Switchblade on the descents just as much as climbing and on flatter trails.

But that support comes with a cost. There’s a certain level of “plushness” that is missing when hauling through a chunky trail with repeated mid-sized hits at speed. The Switchblade tends to feel a bit more violent than other bikes in its travel class when put in these situations. I want to be clear, however, that I don’t necessarily view this as a bad thing. That slight lack of plushness is welcome when the trail is smoother or large g-outs occur, where the Switchblade feels supportive and not “mushy.” Going forward, I’ll be changing some suspension settings to see if I can get a slightly more muted ride in chunky descents while maintaining the supportive platform for pedaling.

Also, for a reason I can’t yet pin down, the Switchblade is just plain noisier on descents than I’m used to. Sometimes it’s easy to isolate these noises as something I did wrong during assembly and sometimes I think it’s due to the inherent design elements of a component. I’ll be sure to update this aspect of the review after I’m able to do a bit more detective work.

As for the drivetrain, the Shimano XTR components have been flawless so far. As is typical in my experience, the noise of the Shimano drivetrain is muted compared to SRAM and the XTR shifts much more effortlessly, though a part of me does miss the positive ka-clunk from SRAM drivetrains. The XTR’s shifting under load is also greatly improved compared to competing drivetrains (and past Shimano drivetrains).

The four-piston XTR brakes have been perhaps the biggest surprise. I’m usually extremely wary of any non-gravity-oriented brakes on a bike (Codes and Saints for life!), but the XTR M9120 brakes have been, thus far, pretty good with a solid initial bite and more modulation than I expected.

As we get more time with the Switchblade, we will be updating our ride impressions. We also have a few questions out to Pivot for clarification on some details regarding the builds and the frame itself, so stay tuned for those updates.

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) Can we get a more “plush” feel out of the Switchblade on the descents while maintaining the awesome pedaling efficiency it has demonstrated so far?

(2) Over the course of the review, will we find any changes in terms of how noisy the bike is, or find some solutions?

(3) Will the Switchblade’s more tame, less extreme geometry still appeal to us as we get more comfortable on the bike and push it harder, or will we be wishing for slacker and / or longer geometry?

(4) This bike is billed as a middle-of-the-road, do-everything option. Given that, we’re curious about the kind(s) of riders we think will get along best with the Switchblade, and if it excels or falls short in any particular scenario.

Bottom Line (For Now)

Pivot Cycles has re-released their do-everything bike, and initially, the new Switchblade seems like a very competitive option in the “Goldilocks” category. We are looking forward to getting more trail time with the Switchblade to further figure out who would appreciate it the most, so stay tuned for our long-term review.

Full Review

Ben Sims: Eric Freson, Dylan Wood, and I now have quite a bit of time with the Switchblade, so here we’ll all be chiming in on this versatile Trail / Enduro / whatever-you-want-to-call-it bike.

When we left off in our First Look, I was impressed by the Switchblade. After a handful of rides, it was clear that Pivot made an effort to evolve their flagship Trail bike, rather than try to reinvent it. Frankly, I find Pivot’s perspective to be refreshing for a number of reasons. Chiefly among those being, despite what you may have seen in certain marketing copy, there’s a lot more to making a bike ride well than making it longer and slacker. Geometry is a huge part of a bike’s performance, but every bike doesn’t need to have the same numbers, since every rider isn’t the same. Pivot seems to understand this and hasn’t gone overboard in chasing the most aggressive ~140mm-travel bike possible. After all, this class of bike is intended to be versatile, first and foremost.

Eric Freson: I’d definitely agree with Ben here. When I think of Pivot, as a brand, one of the first thoughts that floats through my head is “well engineered.” And the Switchblade is on point here. Between the geometry, general design features of the frame, and the spec of the build, the overall package feels complementary. Pivot spec’d components that accurately match the bike’s intent, tuned frame compliance and ride quality nicely to balance comfort and precision, and chose geometry numbers that help to make the bike feel at home in a broad spectrum of terrain.

More Thoughts on Fit & Geometry

Eric (5’10”, 165 lbs / 178 cm, 75 kg; Ape Index +1.5; Inseam 31″ / 79 cm): I found the geometry of the Switchblade to be very well suited for a bike that could see a huge variety in terms of terrain type, riding style, and intended use. Personally, I tried the flip chip in the “high” setting for one ride, but otherwise left it in its “low” setting. And overall, the size Medium Switchblade worked quite well for most of the riding I did on it, though if it were my own bike, I’d be considering sizing up since I’m right on the fence between Pivot’s recommended size for this bike.

While we just touched on the potential upsides of not going wild with the longer / slacker trend, I’d personally like the Switchblade a bit more if its headtube angle was just slightly slacker, as a means to calm things down just touch in the front-end / rider-input department, as at times the Switchblade can be a bit frenetic when trail speeds get high. The Switchblade is definitely on the quicker / sharper-handling end of the spectrum, and rapidly translates rider inputs into changes on trail. On one hand, that’s going to make it really appealing to folks who find modern bikes in this class too sluggish / boring, but on the other hand, it’ll make the Switchblade a bit less appealing to people who favor the calm ride of more slack bikes (more on that later).

Dylan Wood (5’11”, 155 lbs / 180 cm, 70 kg; Ape Index +0.5; Inseam 32” / 81 cm): I agree with Eric here. Overall, the Switchblade’s geometry makes a lot of sense for a do-it-all Trail bike. That said, I too was a fan of the “low” geometry setting, and didn’t see a need to ever switch it into the “high” setting, even when riding relatively mellow, cross-country-style trails. Given that, I agree that a slightly slacker headtube angle would be welcome, as the Switchblade sometimes felt a little quicker and more responsive to slight changes in steering and weight distribution than I’d personally like.

More Thoughts on Team XTR Build

Eric: I loved the Reynolds Black Label Wide Trail 349 wheels and XTR drivetrain on a bike like this, where you often find yourself attacking the trail both while climbing and descending. The wheels are stiff, light, and wide, for excellent tire support. Given their low weight and stiffness, they’re quick to spin up when putting the power down, and easy to place and keep on line when pointed downhill.

The XTR drivetrain shifts well under load, initiates gear changes quickly, and encourages you to shift more often to stay in your legs’ proverbial “power band,” rather than sitting back and spinning. Especially combined with the Switchblade’s efficient DW-Link suspension, it encouraged me to bang through gears both while climbing and descending, and I was up over the front end of the bike more often as a result. Overall, the Switchblade Team XTR was built just like I’d build my own if I owned one. Or nearly — I do think I’d run a Fox Float X2 or DHX2 personally, as you can feel the DPX2 working hard when trails get rockier, particularly over longer descents. But overall, I have no complaints, and I’d be pretty bummed if I did, given this build’s high price.

Dylan: Agreed, this bike is spec’d with a very nice build kit that complements its intended use. The wheels felt stiff and precise, and despite how light they felt, I never worried that I was bashing them too hard.

The XTR drivetrain is super smooth, both while upshifting and downshifting. I think just about every mountain biker who has been riding for a few years has developed a habit of slightly dialing down the power when actively shifting to allow their drivetrain to shift smoothly and quietly. With the Shimano XTR groupset, I felt as if I did not need to skip a beat when shifting and could continue with the same watts and cadence as I would when staying in one individual gear when actively shifting in either direction. Smooth and quiet, as a high-level drivetrain should be.

Depending on your riding style, you might find that the DPX2 shock gets overwhelmed too easily. I mostly rode the Switchblade on the relatively mellow trails of Hartman Rocks, and I thought the DPX2 was well suited there. For that sort of riding, I think a heavier, burlier rear shock would have more downsides than it would have benefits. However, when riding chunkier, steeper, more sustained trails, the DPX2 couldn’t quite keep up with each successive hit and faded slightly. My guess is that around 90% of riders could get along just fine with the DPX2 on the Switchblade, and for the other 10% — riders who feel they can overwhelm a non-downhill-oriented rear shock — you probably already know who you are.

General On-Trail Impressions

Ben: At the time of publishing my initial impressions, we were still left with some questions about the Switchblade.

The biggest issue I faced with the Switchblade was dialing in as much plushness and traction as I wanted from the rear end of the bike in chunkier situations while descending. This became a non-issue once I stopped paying too much attention to the recommended suspension settings provided by Pivot.

When trying to set up the DPX2 to Pivot’s recommendation, I found that they were recommending the three-position climb switch in the middle position for riders of my weight, which resulted in quite a lot of low-speed compression damping. This was confusing to me, since I had never had anyone recommend that switch be anywhere but in the open position, unless I was climbing or riding smooth flow trails. Fine-tuning the compression for my preference was made tougher by having the switch in the middle position — the fine adjustment screw only applies in the open setting. So I went back to the full open position and then backed off the low-speed compression screw to almost fully open.

To Pivot’s credit, they’re trying to make the suspension setup less of a mystery for consumers, and the recommended settings are merely intended as a starting point. But this is where I implore riders to learn about bike setup in a way that is meaningful to your riding. I was eventually able to find a great balance of mid-stroke support while climbing and moderately plush but poppy ride characteristics while descending by running the recommended sag (16.5 mm), a fully open climb switch, and two clicks from fully open (soft) low-speed compression.

With these settings, I fortunately feel the same way about the Switchblade’s climbing ability as I did in the initial look. With lighter compression damping settings, the DW-Link design still felt extremely supportive during technical climbing situations and I was able to alternate steady seated climbing and out-of-saddle bursts with equal aplomb. This bike climbs better than any non-electrified 140mm-travel bike that I’ve ever ridden in any climbing situation I put it in. That willingness to climb is a real feather in Pivot’s cap.

That sprightliness does come with, depending on your perspective, some drawbacks. Though I was able to dial in a more planted feel on descents with suspension settings that were more focused on my preferences, it didn’t magically transform the bike into an Enduro sled. The Switchblade was marginally more planted, marginally less poppy, and altogether slightly more capable for anything I threw at it, after adjusting the suspension. None of that is a bad thing. But the Switchblade still has a moderate wheelbase (1193 mm for our size Medium test bike), and that does impose a limit on how stable and composed the Switchblade can be at very high speeds in rough terrain. No matter what suspension settings a rider uses, it will always be hard for the Switchblade to match the stability of, say, a 1250mm-wheelbase bike with longer chainstays, longer front center, and / or a way slacker headtube angle.

All that said, Pivot preserved a lot of maneuverability by not going longer and slacker with the Switchblade. And, as I’ve said before, kudos to them for doing so. They have engineered a carbon frame that is extremely stable for a “shorter” 142mm-travel bike. While the industry was releasing longer bikes and saying matter-of-factly that they were “better,” Pivot kept their geometry tamer. For the style of riding I do in Colorado, where the bike needs to be capable on chunky, technical climbs and smoother fire roads alike, the moderate length of the Switchblade was a welcome departure from many bikes in its category. Is it “better?” That just depends on your own preferences.

So to answer two of the questions from our initial impressions: (1) yes I was able to find some more traction / plushness by judiciously focusing on my own riding and setting up the suspension appropriately. And (2) yes, this in turn made me appreciate the Switchblade’s less aggressive geometry even more, particularly in technical climbing situations and in lower-speed descents when I needed maximum maneuverability.

Eric: I would also describe the ride of the Switchblade as supportive, both when climbing and descending.

I found the Switchblade to be an excellent climber. I enjoy DW-Link bikes, and the Switchblade was no exception. The leverage curve and shock tune work well in conjunction together, and rear-end traction was excellent without spiking. I almost never adjusted the shock’s climb switch, generally choosing to keep it wide open.

On the way down, I found the Switchblade to be most rewarding on terrain that encourages carrying momentum, and using the trail itself to build speed by pumping and sneaking pedal strokes when possible, rather than just pointing straight down something super steep. In these instances, the Switchblade shines. It has a very impressive ability to feel both active and efficient in these situations. The Switchblade isn’t what I would reach for if I preferred to let the suspension do all the work plowing through rougher sections; for a more planted, plow-y ~140mm-travel bike, the Santa Cruz Hightower or Guerrilla Gravity Smash would be better calls. The Switchblade is a bike that encourages a more active style with more rider input. On fast, flowy, or pumpy trails, this results in a bike that begs to attack the trail. On rougher terrain, this same characteristic meant that I was using more of my legs and arms to help keep the bike on line and from getting kicked around a bit more than I’d like.

When trails did skew rougher, especially with frequent suspension-compression situations, the Switchblade did remind me that it’s only working with 142 mm of rear-wheel travel. In these instances, I can feel the back end hanging up a bit over successive large compressions, and the DPX2’s rebound tune struggles a bit to keep here. The progressive nature of the bike meant I never experienced any harsh bottoming-out, and the ramp-up helped me know where I was in the shock’s travel, but it was not a feeling of bottomless suspension, either. Not a problem by any means, but a reminder I wasn’t riding a bike with ~160 mm of rear travel, like my Pivot Firebird.

Dylan: I also agree with Eric and Ben, the Switchblade feels supportive and responsive.

Uphill, the DW-Link suspension provides an impressively efficient platform. I rode mostly smooth trails where traction wasn’t really an issue, and I still felt that I did not need to touch the climb switch on the DPX2. If you want a bike in this category that compromises little compared to shorter-travel alternatives, the Switchblade warrants a very close look.

I think Eric said it best: the Switchblade encourages you to ride with a dynamic style, pumping and popping over trail features. It has a very responsive and energetic feel, convincing me to really push into the trail and get more speed out of every possible opportunity. This makes the Switchblade really fun in certain scenarios where other ~140 mm Trail bikes, such as the Santa Cruz Hightower, feel excessively big and sluggish.

Unsurprisingly, the Switchblade keeps this responsive and sporty feel in chunkier, technical terrain. It requires a little bit more work on my end to absorb impacts and maintain traction in rock gardens and rooty sections of trail. I agree with Eric in that a more planted, plush bike like the Hightower offers a more forgiving and smooth ride through rough sections. However, this same characteristic of the Switchblade means that some well-timed weighting and unweighting of the bike can result in faster exit speed of chunky sections of trail than on other bikes that feel less responsive.

Other Notes

Ben: At 5’10”, I got along well with the size Medium Switchblade but I could potentially ride a size Large. That would mean only an increase of 15 mm in reach and lengthen the bike from a 1193 mm wheelbase to 1216 mm. Add in the fact that the Switchblade is coil-shock capable, and well, you can probably see where I’m going with this. Would I lose some climbing ability with a Large Switchblade + coil shock? Almost certainly yes. Would the bike get closer to that EWS sled category? Yes … just ask Ed Masters or Bernard Kerr. They’ve raced on Switchblades with coil shocks. But I suspect that, for those between sizes or looking to get some more plushness from the Switchblade while still maintaining what I suspect would be a very efficient, quick-handling bike, I think that’d be worth considering.

We asked Pivot about the DT Swiss wheels now spec’d in place of the Reynolds upgrade option that our test bike came with — blame COVID and supply chain disruption. The DT Swiss XMC1501 is now the carbon-upgrade wheel option on the Switchblade for the time being.

As for the rattling noise I noted in our initial impressions, I did switch out the brake pads and… it’s better. I liked the Shimano M8120 brakes. I didn’t notice any of the wandering bite-point issues that some riders have mentioned about other Shimano brakes, and for the most part, think they’re pretty solid, though not as powerful as true DH-oriented four-piston brakes, such as Shimano Saints, SRAM Codes, or Hayes Dominion A4. That said, those Shimano finned pads were absolutely the culprit for quite a bit of noise. I’m not the first bike rider to note this and likely won’t be the last. Shimano, nice work on the M8120 stoppers, but please fix the pad noise. I tossed the finned pads back in the bike before giving it to Eric so he can offer up his thoughts as well.

Eric: Shimano finned brake pads have been noisy on a number of different bikes I have spent time on, including the Switchblade. But I think what I noticed most in regard to the Switchblade’s decibel levels had more to do with chain noise. I think a lot of this is down to the relatively fast rebound tune on the rear shock, and the tendency of the rear end of the bike to be active in rough or rocky sections of trail. The XTR rear derailleur kept my chain in place almost at all times during my time with it, but I did lose it twice. If this were my bike, I think I’d run an upper guide.

Ben: Great point Eric. In my initial review, I was having trouble completely isolating why the bike was noisy. And the pads were definitely part of it. But you’re 100% correct, there was something else going on from a noise perspective.

Dylan: The Switchblade did have some chain slap noise, but nothing obnoxious in my experience. Although I never lost the chain, if this were my bike, I would add an upper chain guide as well as a bash guard, because upper chain guides have few downsides in my opinion and I tend to bash my chainring on rocks, and would rather not worry about damaging anything.

Who’s It For?

Ben: So, who will get along best with the Pivot Switchblade? Honestly, it’s a better exercise in discerning who won’t be a good fit for the Switchblade. Pivot has done a great job of building a bike that I think many riders will get along with well.

More aggressive riders will potentially want more descending stability and overall heft from the Switchblade. And while my opinion is that those riders are misrepresenting what they should expect of a 142mm-travel bike, they might feel like the Switchblade should be longer and slacker. Fortunately, there are tons of other options today that fit that criterion.

Personally speaking, I’d take the Switchblade to the park when the lifts spin and feel like I wasn’t too undergunned. But I’m not an expert park rider. Similarly, there might be some people who are looking for a nimble pedal-all-day Trail bike and they look at the Switchblade as too burly / long-travel for their purposes. To those folks, I’d say that the Switchblade pedals and maneuvers far “smaller” than its travel numbers would suggest (and it’d also be worth checking out the Pivot Trail 429, which we’ve been spending time on). To summarize, people looking for a true XC bike, or an ultra–burly Enduro sled need not apply.

That leaves all the folks in between who are merely looking for a bike that can feel quite capable in the most scenarios. The bike industry is tackling the Trail / All-Mountain / Light Enduro bike category in myriad ways at the moment. The Pivot Switchblade strikes me as one of the most well-rounded and versatile of all, and I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it to anyone who wants a solid-performing, very-good-pedaling, good-descending, true all ‘rounder mountain bike. Particularly if you value efficient pedaling performance and sharper handling over a super planted, ultra-stable ride.

Eric: To me the Switchblade feels like an excellent choice for a huge range of riders and terrain types, keeping it aligned with its scope and mission. This is a bike that I think will exceed many riders’ needs about 80% of the time. And if that 10% on either end of the spectrum is critical to you, you probably already make compromises / choices about the type of bike you ride to reflect that. If you are someone who almost exclusively rides extremely rocky terrain, frequents bike parks, or want something that does the work for you at high speeds on rough trails, the Switchblade wouldn’t be my first choice. But for the rider looking for an active, fast bike that is going to keep you engaged with the trail and smiling, it’s an excellent choice. It’s fast, both up and down. It’s a lot of fun, because it rewards energy invested with speed. It’s practical in a way many longer-travel bikes aren’t — compared to the likes of the Santa Cruz Megatower, Guerrilla Gravity Gnarvana, and especially the Nicolai G16, the Switchblade is far more at home on more rolling terrain, and doing things other than attacking a steep descent with the aggression turned up to 11. For someone who wants a bike that encourages play, fun, and creativity on the trails they ride, it’s going to be extremely rewarding.

Dylan: The Switchblade stands out in terms of how versatile and lively it is for a ~140 mm Trail bike. This does come with tradeoffs in terms of how forgiving the Switchblade is at high speeds in rough terrain, but they’re relatively minor in my opinion, and the Switchblade provides a sporty ride where other bikes feel dead (even those with similar amounts of travel). This being said, if you constantly ride really chunky terrain, want a more planted feel, and don’t mind a bike that feels less sprightly on mellow terrain and while climbing, then there are more forgiving and practical bikes — again, the Santa Cruz Hightower would be an obvious call here.

Bottom Line

The Pivot Switchblade is a very versatile, ~140mm-travel Trail bike that we think will work well for a whole lot of riders looking for a bike that can cover a lot of bases, from long backcountry rides, to some more aggressive descending, and maybe even occasional bike-park use.

It’s neither a rocketship XC bike, nor a super aggressive Enduro rig, but catering to either of those ends of the spectrum would mitigate the versatility that is the point of the Switchblade to begin with. It climbs great, in both smoother and more technical terrain, and is a capable descender, as long as you’re willing to put some effort in and don’t expect it to absolutely steamroll every bit of trail you might point it down. That’s a middle ground that will suit a lot of riders well, and Pivot has hit their mark with the latest Switchblade.

How would you compare this to an Ibis Ripmo? The geometry looks very similar to the V1.

Tom,

I don’t personally have any time on the Ripmo V1, Ripmo V2, or Ripmo AF. We did review a Ripmo V1 a few years ago, and you can read that here. https://blisterreview.com/gear-reviews/2018-ibis-ripmo

In my opinion, generally speaking, geometry can play a big role in explaining whether a bike will fit you or not. And my guess is that I’d fit a Ripmo V1 size Medium pretty easily, just comparing geometry charts of the two bikes. But the linkages on Pivot and Ibis, though both a form of DW link, are different. And further, the shock tunes are different as well. And I’d also venture a guess that the carbon layups allow for slightly different flex characteristics. Those three aspects play a big role in ride quality obviously.

The Ripmo V2 and Ripmo AF are different balls of wax entirely, with longer reaches and wheelbases. We are actively trying to get a Ripmo V2 in to test.

Thanks for reading.

Thanks for the review. I’ve been back and forth between picking up a Ripmo V2 and the Switchblade. Did you feel the medium was the right size for you? I’m also 5’10” and about 175 lbs with a 31″ inseam and reading Pivot’s sizing charts seem to be between medium and large. Reading other feedback I’d actually been leaning towards a large in the bike. No local demo centers unfortunately.

Seth,

I’ll have more to say as I get more time, but for now, I’m pretty settled on a Medium as my preference. For three reasons. 1) my personal bike has a reach somewhere around 425 mm, and I do enjoy the “short-coupled” feel it provides. Though, to be clear, I need to upgrade in the next year or so 2) A size Large Switchblade has a reach of 470 mm and a wheelbase of 1216mm. Those numbers indicate a potential loss of technical climbing and slow speed maneuverability ability, while slightly increasing stability for descents. 3) I tend to enjoy the technique of riding in a more upright “ready position” rather than always being up over the front end in “attack position.” Which translates to me enjoying a slightly less stretched out feel than some of the longer bikes out there.

Your personal feelings on those points may guide your decision towards a Medium or Large.

If you call it a reverse mullet again I will be upset. It doesn’t get any more business than a 29er or more party than 27.5

Ha, that was deliberately in quotes — it’s the phrasing Pivot used in their press release…

Well I guess pivot is having a 29er party down there in Arizona. I shant be the one to stop them

Leo,

In edits, Luke and I dutifully researched and learned about mullets. First as a fish, then their use as a hair style, and finally as a term to define bikes with different size wheels front to back. Trust that here at Blister, misuse of the word “mullet” is never our intention. We went with Pivot’s press release terminology.

In all seriousness I’m excited to see the review. It’s interesting to see clues that bike geometry might be settling in on a happy medium.

Leo,

Just as there is room for all different kinds of skis, there is room for all different sorts of bikes. That’s said, here in the Year of Ellsworth, skis seems to have stopped their downward march in weight. In my opinion, I think we will soon see a similarly more pragmatic approach to head angles and overall bike length in the next few years. Cheers and thanks for reading.

Looking at a pivot race Xo1 , or a Hightower c s with SC reserve wheel upgrade. Any thoughts. I ride primarily in New England.

Cheers

Hey David –

What bike did you end up going with? I also live in New England (Connecticut), and am looking at the Switchblade. I looked at the Hightower, and rode the V1 Hightower, but it didn’t feel very lively compared to my SC 5010 (I know, 27.5 compared to 29), but the numbers and geo look so similar between the Switchblade and my 5010, that I think it could be a great choice for me. Wondering where you landed on this, and what your thoughts are?

Thanks,

Adam

Pivot prefers their bikes, the switchblade in particular, to be set up very supportive to match what their enduro riders prefer for racing. I work in a shop and our pivot rep set my blade up VERY VERY firm, and he dialed it back from what the brand says. I just dont slam my bike that hard to need that much support, and found it to not work for me in tech terrain. I had to air down a bit, and will probably need to remove one of the volume spacers in the rear shock (I think it comes with two installed).

Spence,

Thanks for the comments. I was picking up my personal bike today at my bike shop (also a Pivot dealer) and got into a lengthy conversation about how I might change the suspension settings for a less firm ride. We will absolutely report back on the ride quality when I’ve had a chance to dial in some plushness on it.

Any thoughts/comparison to the Mach 5.5? Though there’s some minor differences in the geo, they almost appear to be pretty close to one-another. Sounds like the ‘Blade may be the better climber? Great review, as always. Thanks!

AlpineIce,

Good news for you, I’ll be handing off the Switchblade to Eric Freson, who wrote our Pivot Mach 5.5 review, in a couple weeks. You can read his impressions of the Mach 5.5 here. https://blisterreview.com/gear-reviews/2019-pivot-mach-5-5-carbon-live-valve

Eric called the Mach 5.5 “an exceptional generalist.” I’d absolutely characterize the Switchblade as that. Up till now I’ve setup the suspension on Pivot’s recommended settings from their website. I’m excited to start tinkering with the settings to dial the bike into my personal preferences and see if it still pedals as well, and can calm down a bit on descents. I’ll be sure to update the review. And Eric will be well-positioned to make the Mach 5.5 comparison for you soon.

Any word yet as to why Pivot no longer specs the Team XTR and higher end models with the Reynolds wheels? Why the change to DT Swiss?

Randy,

I’ll be updating the review above with Eric’s thoughts and answers to our questions in the coming weeks, including this question. But, short answer, Reynolds hasn’t been immune (pun intended) to COVID-caused supply chain issues. Pivot needed a rock-solid supplier for the wheel upgrade and they decided to use DT Swiss for now. They assure me that their long relationship with Reynolds is strong.

I just ordered a Switchblade Team XX1 AXS build. However, I will be using different tires: Going with the newly designed Schwalbe Magic Mary 2.6/ Super Trail/ ADDIX Soft up front and the newly designed Nobby Nic 2.6/ Super Trail/ ADDIX Soft in the rear. Schwalbe redesigned their entire tire lineup as of June 2020 and initial reviews are looking very good. Many riders may not be aware that the conventional Maxxis tires used in most new bike builds are about 10 years old. The cheapest way to get a different riding experience is to change your tires! Also, I’m looking forward to taking advantage of the fact that Pivot has clearance for 29 X 2.6 tires front and rear. That is definitely worth taking advantage of and puts the bike in the very rare “Mid Plus” 29er category, as Schwalbe tires tend to run a bit wider than official measurements. Living in the Pacific Northwest, this tire arrangement is great for my conditions.

Here is a link to an article of the newly redesigned Schwalbe mountain bike tires for 2020: https://enduro-mtb.com/en/schwalbe-mountain-bike-tires-review/

You guys have the best reviews! Explain the equipment, explain what it means, give comparisons, and feedback. Well done.

Too kind Thomas. I can safely say it’s a labor of love for the entire team.

Looking at the Switchblade and possibly the esker Rowl. Any more ride impression updates on the pivot?

Thanks!

Steve,

Standby, Eric Freson and I will be giving our final thoughts on the Switchblade soon

Id be interested to hear more intricate details to your suspension setting to soften up the rear end for medium range chatter. To much air out and your sitting to low in the travel and riding middle compression, to high and its compression off the top. I guess with all the different weights and sizes maybe a percentage of sag would best indicate where you found the ideal set up.

Thanks,

Great review

How it compare to yeti sb 130 lr?

James,

I’ll be updating the review soon, to include answers to these very questions. Spoiler alert, I was able to make some pretty positive changes from a plushness perspective without killing the the bike’s willingness to pedal.

Great review and responses to others questions. On a Tallboy V4 right now and love it. However, I just sold my Blur and am thinking about the Switchblade and this review really helped me based on your detailed analysis of the bike. I want a bike that climbs well and handles the downhill well. I am not a big jump or drop guy, but love riding technical trails like Gooseberry Mesa. Thoughts on this being a good bike for southern Utah’s trails?

Doug,

Eric and I have both written our final comments on the Switchblade and hope to finish editing it soon (no promises, there’s snow falling in CO!). Hopefully his input and my final thoughts can shed some light on your question.

I will offer a short teaser though: The Switchblade seems to effectively cover the middle 80% of the mountain bike world quite well.

Great review! I swapped in the DVO Jade X for Plushness is $$$, and I totally agree that it was lacking in that area with the air shock. Much better grip with the coil. I’m throwing on DVO Onyx Sc1 shortly to go with it, debating overforking it to 170mm. Also added a wolftooth 1* angleset for Nor Cal’s steeps and it feels a lot more stable at higher speeds and is still agile as hell.

(Initially purchased the race gx/xo1 build)

Great update,

I also found a good sweet spot in the rear after “going my own way”. I’ve gone 2-4% more in sag, lever always open and compression at 4 out. I do often switch between flats/spd’s and when running flats add a click or 2 more rebound speed. I’ve found connectivity to flats better this way with DW’s design.

Riding Canada’s east coast I also switch back and forth the H/L chip. Our trails, comprised of large granite slabs, roots, jagged ascents/descents with sharp trail changes the high setting is beneficial. Any time we head to proper hills with ample descent low is the way to go. Given the amount of worldwide locations this bike will be ridden I feel the flip chip can certainly be useful. It’s written off in most reviews but most reviews take place in Squamish, Colorado etc… Our dream riding locations for sure but not most of our realities.

Only question I’d ask is bar width? I’m still running the factory 780mm width and at 6’2 I certainly should be. However I’ve found with the Switchblade being such a poppy/ flow bike I’m getting much more lift with my hands moved inboard slightly. I assume the strength and lift is better due to better alignment with my shoulders and the ideal strength position.

The question is do I want to take away a slight amount of high speed stability for more responsive power moves by trimming my bars? Given my location and riding type. I’m considering it.

I’m riding the Pro XT/XTR build which I’m sure is most common with DTSwiss aluminum wheels . They work superbly. I wouldn’t bother with the carbon upgrade. I will however update the Race face cranks once they’ve seen a full season.

Best reviews online Blister,

Thanks for that.

James G,

Thanks for the compliments. We appreciate it. I’ll try and address a few of your comments.

I think you’re prudent to adjust rebound for pedals (quicker for flats). Good on you for experimenting and finding what works for YOU. As I said in the review, I wish more riders would do this.

You’re correct about many bike reviews being in places where it pays to have ultra-stable bikes. I try to wring out ride impressions just as much on rolling and smooth terrain as I do on chunkier and steeper tracks. Hopefully you can read our update above and see how we characterized what this bike does on terrain like your home area.

Handlebar width? Best test is to do push-ups with whatever grip feels most efficient, powerful, and comfortable. For me, that’s 780mm. Someone much more powerful and broad than myself, Richie Rude, rides 750mm bars for reference.

I’m a fan of well-built alloy wheels too. I’ve reviewed some terrific carbon hoops, but you’ll find Aluminum rims on all my bikes.

Cheers.

Thanks for the excellent review! Curious to know your thoughts on pro’s/con’s between Mach 5.5 and the Switchblade…in which scenarios you would choose one over the other? I won’t be able to demo either as there aren’t any demos in my size (XS 27.5). I have to choose based upon reviews, geometry, etc. so I really appreciate your guys’ thoroughness reviewing this bike. (I did read the Mach 5.5 review, but I’m not clear when comparing the two.)

One other question on that…given my size & body mechanics, I need shorter cranks. 150-ish. Do you see any reason why either of these bikes – or Pivot bikes in general w/Super Boost Plus – would make that more difficult? Thanks for your thoughts!

Comparison between Pivot Switchblade v2 vs Yeti 130LR vs SC Hightower vs. Ripmo V2?

I’m be getting a new bike and looking to demo the above bikes. I’m be interested in getting Ben, Eric and Dylan’s opinions as it’s not the easiest to get demo rides in with Covid…

To put context around me and what I’m looking for: I’m a 6′ / 175 lbs / 55 year old guy who rides 3 to 4x a week (road x2 and mountain x2). I’ve got a 29er hardtail for XC longer days and am looking for a full suspension that gives me a bit more travel to “save my a**” than a Tallboy or Ripley. Typical full suspension ride will be 10 to 25 miles with 2 to 4K climbing. I ride SF Bay Area (Northern CA). Last FS bike was a Gen 1 Hightower. I’ve been a long time Santa Cruz VPP rider but open to other suspension design. Majority of trails I’ll be riding are tight single-track in trees with rock garden sections, but more tight off camber switchbacks and roots. I will prioritize “tires on the ground maneuverable” vs “straight line bash through chunky rock gardens”. I am 55 after all and don’t recover from a good crash as quickly as I used to. Efficient climbing is a big deal. The focus on climbing will be on technical steep rocky / rooty climbs. Smooth fire roads are easy for any bike these days. Based on your review of the the Pivot Swtichblade it seems like it fits my criteria the best based, but interested to hear your opinions as your didn’t compare it to the Yeti 130 (I’m more interested in the 130LR Lunch Ride). Also, since Pivot has updated the Switchblade to use the new Float X (like Yeti does) do you think that will change your opinions for the positive as the DPX2 seemed to have some limitations. Thanks for all your help.

Rich,

See reply in my bio. Thanks.

The new Switchblade looks like a solid contender and I am about to place an order; but one thing concerns me. The press fit bottom bracket. I keep my bikes about 10 years. You think this will be a problem? Thanks!

Thanks for the great review! I have been riding the new Switchblade for two years now and love most everything about it. However, I have been dealing with one major issue that has really been bothering me and effecting my riding style and confidence. I have had multiple front wheel washouts and the front wheel just does not consistently feel planted through turns. It seems to want to slide around fairly easily. This has never been a problem for me over the past 15 years with my past 3 different Ibis bikes. I live in Nor Cal where our trails are dry and loose, but these are the same trails and conditions I have ridden for over 20 years. I’m also using the same brand/model tire that I’ve used and felt extremely comfortable with for 10 years (2.6 Minion DHF), and run as low of a tire pressure as possible (around 17psi). I even had a friend who is a very good rider try my bike yesterday on the downhill and he also noticed that the front wheel felt like it wanted to jump around and wander a bit more than he was used to. I’m curious if the flip chip could help by switching it into the high setting? I haven’t tried that yet. I have 29 wheels and have kept it in the low setting. I’ve also played with my fork settings and air pressure, but I’m wondering if there are any recommendations that you could make in this regard that might help as well? I have the Fox 36 fork. I demoed the bike several times before purchasing and never felt this way at all on the demo. I’m just baffled as to why the front wheel feels this way and it has really forced me to ride more conservatively on the downhill, which I am not happy about at all. It was a very expensive bike and I don’t want to give up on it yet, but I’m really struggling with this problem. Did any of you feel this way on it and do you have ANY suggestions that might help to improve this issue? I’m desperate! Thank you!

Would be curious to hear Blister staff compare the Occam LT to the Pivot Switchblade. Both bikes profile as fairly conservative geo trail bikes (i.e. shorter wheelbase, steeper HTA) that combine a little extra travel with an efficient pedaling platform. Would love to hear how they match up.