Kavenz VHP 16

Wheel Size: 29’’ or MX

Travel: 160 mm rear / 160–180 mm front

Material: Aluminum

Price: Frames starting from €2,645 ($2,790 at time of publishing)

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- Frame only: 3,357 g

- EXT Stora w/ 375 lb spring: 680 g

- Complete bike, as-built (see below for details): 35.8 lb / 16.2 kg

Intro

High-pivot Enduro bikes are all over the place now, but Kavenz was one of the early adopters, and unlike a lot of the other options in that category, their VHP 16 is meant to be a more versatile, more efficient option that isn’t just focused on downhill performance, and maintains some playfulness along the way. We spoke with Kavenz founder Giacomo Großehagenbrock in Episode 117 of Bikes & Big Ideas about the thinking behind the bike, the overall company ethos, and a whole lot more, which you should check out for a whole lot more info on the story behind the VHP 16.

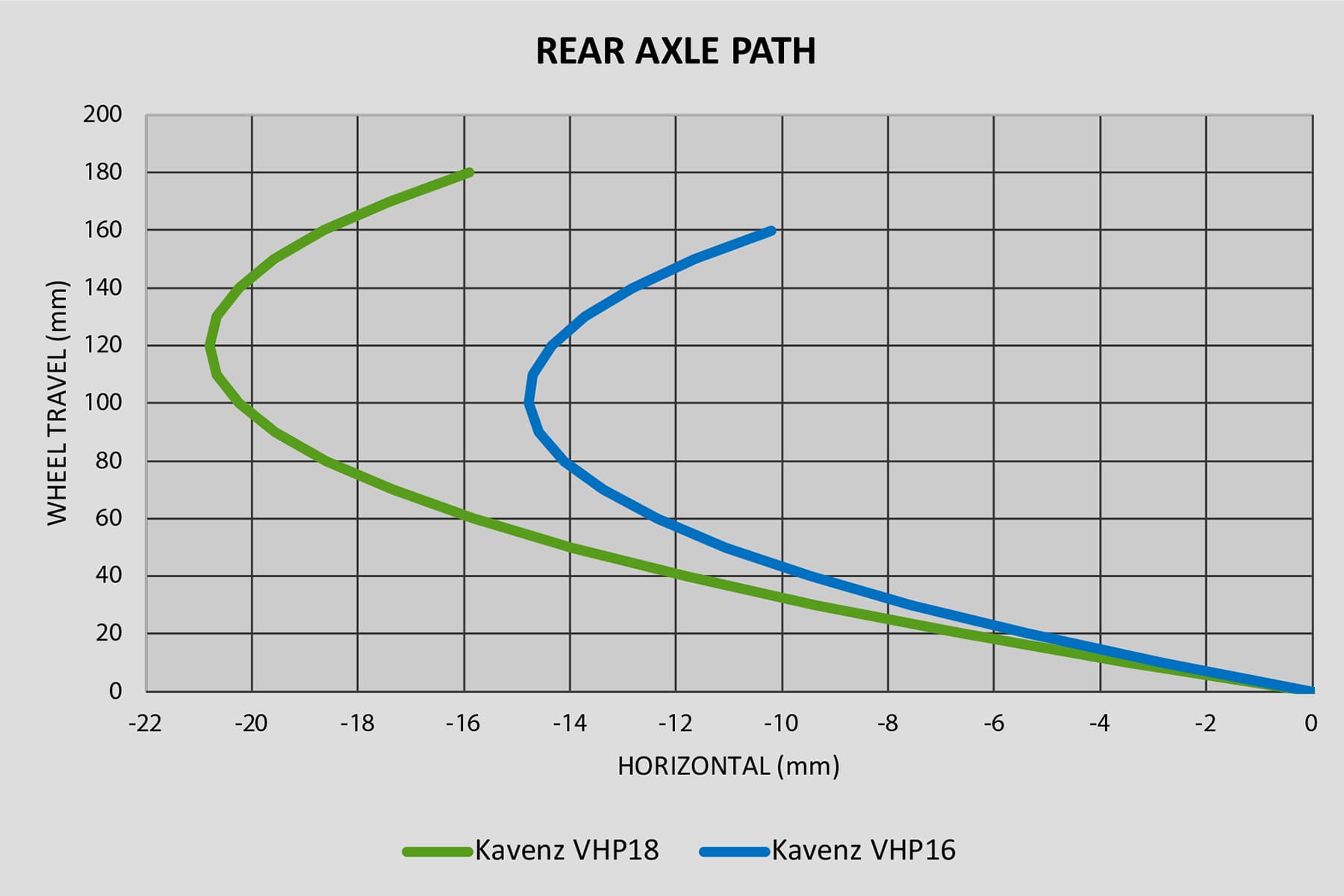

The Frame

The VHP 16 frame is offered in aluminum only, and in a relatively rare move, is made in Germany. It’s what Kavenz refers to as a “virtual high pivot” with 160 mm of rear-wheel travel (hence “VHP 16”) from a Horst-link layout with an idler pulley mounted concentric to the main pivot to keep chain growth and pedal kickback in check. But unlike a lot of other high-pivot bikes, including the Forbidden Dreadnought and Norco Range, the VHP 16’s axle path is only rearward for about the first 100 mm of travel, before coming back forward a bit. That adds up to about 15 mm of total rearward travel before the axle starts to move back forward. The idea is to get a bunch of the benefits of a high-pivot layout when it comes to bump absorption, with more modest swings in chainstay length than you often get from a bike with more rearward travel.

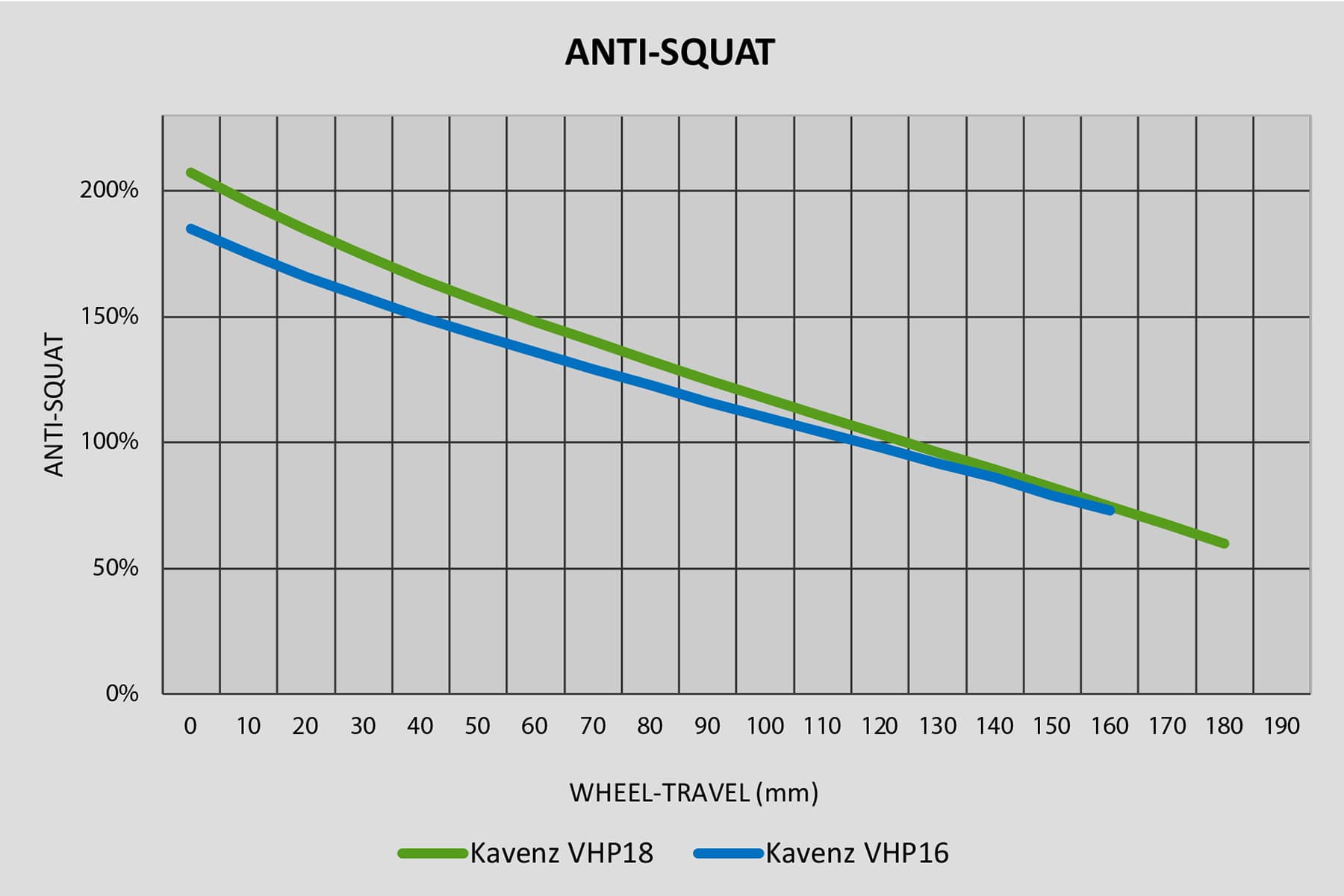

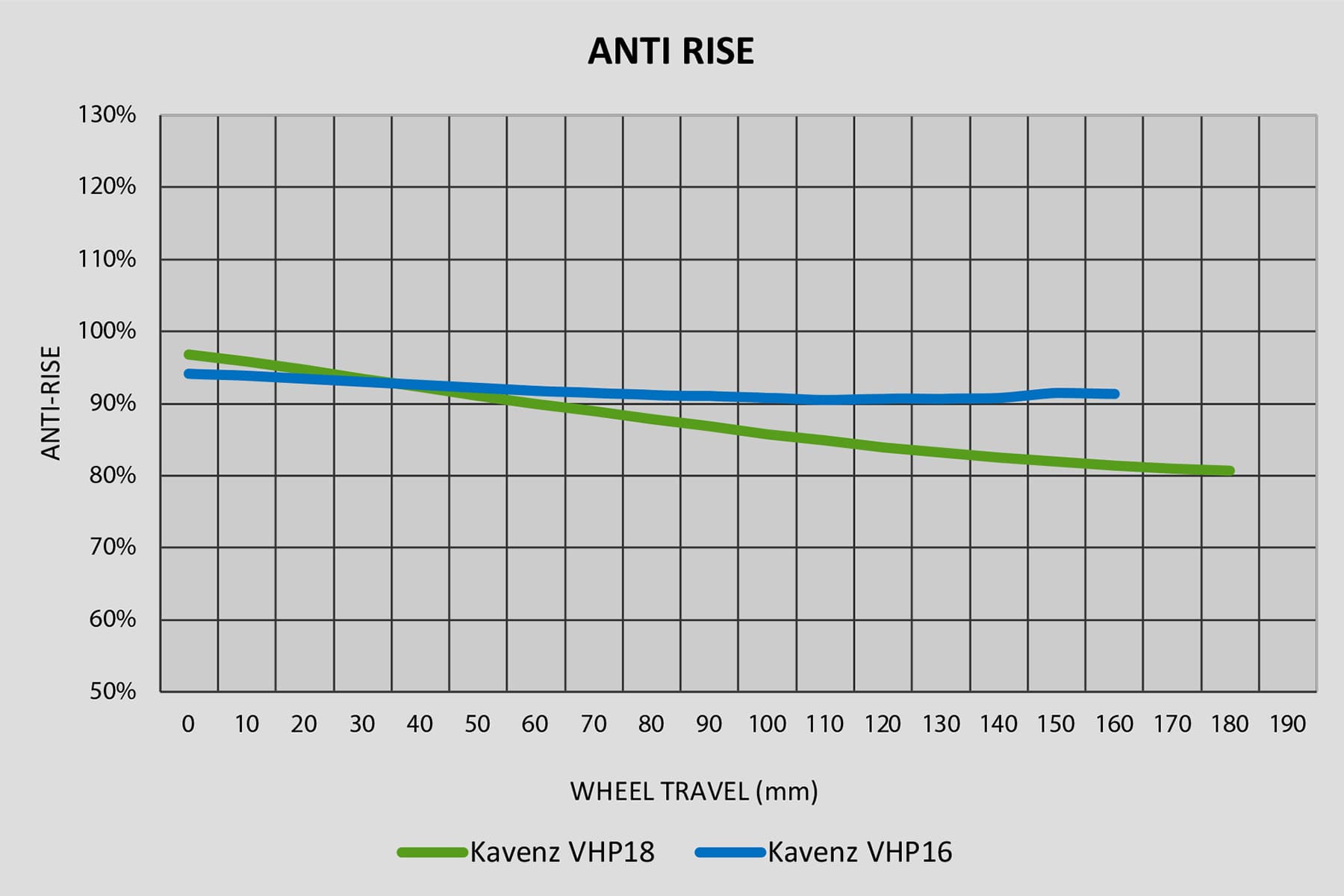

One of the primary design goals of the VHP 16 was to make a high-pivot bike that combines the more rearward axle path and improved bump absorption such a design offers, but with much less anti-rise than you get out of a high-single-pivot layout. In short, bikes with a ton of anti-rise tend to settle deeper into their travel when you’re on the rear brake, both causing the rear suspension to firm up and lose effectiveness and the back of the bike to ride lower, shifting your weight rearward and potentially requiring some active repositioning of your body to counteract. The VHP 16’s anti-rise curve is very flat and sits at just over 90% throughout the travel. That’s still a fair bit of anti-rise (and in theory should make for pretty neutral braking performance) but it’s far less than a lot of other high-pivot bikes — notably the Forbidden Dreadnought, which gave me some trouble with its braking performance and the geometry shifts that came along with it.

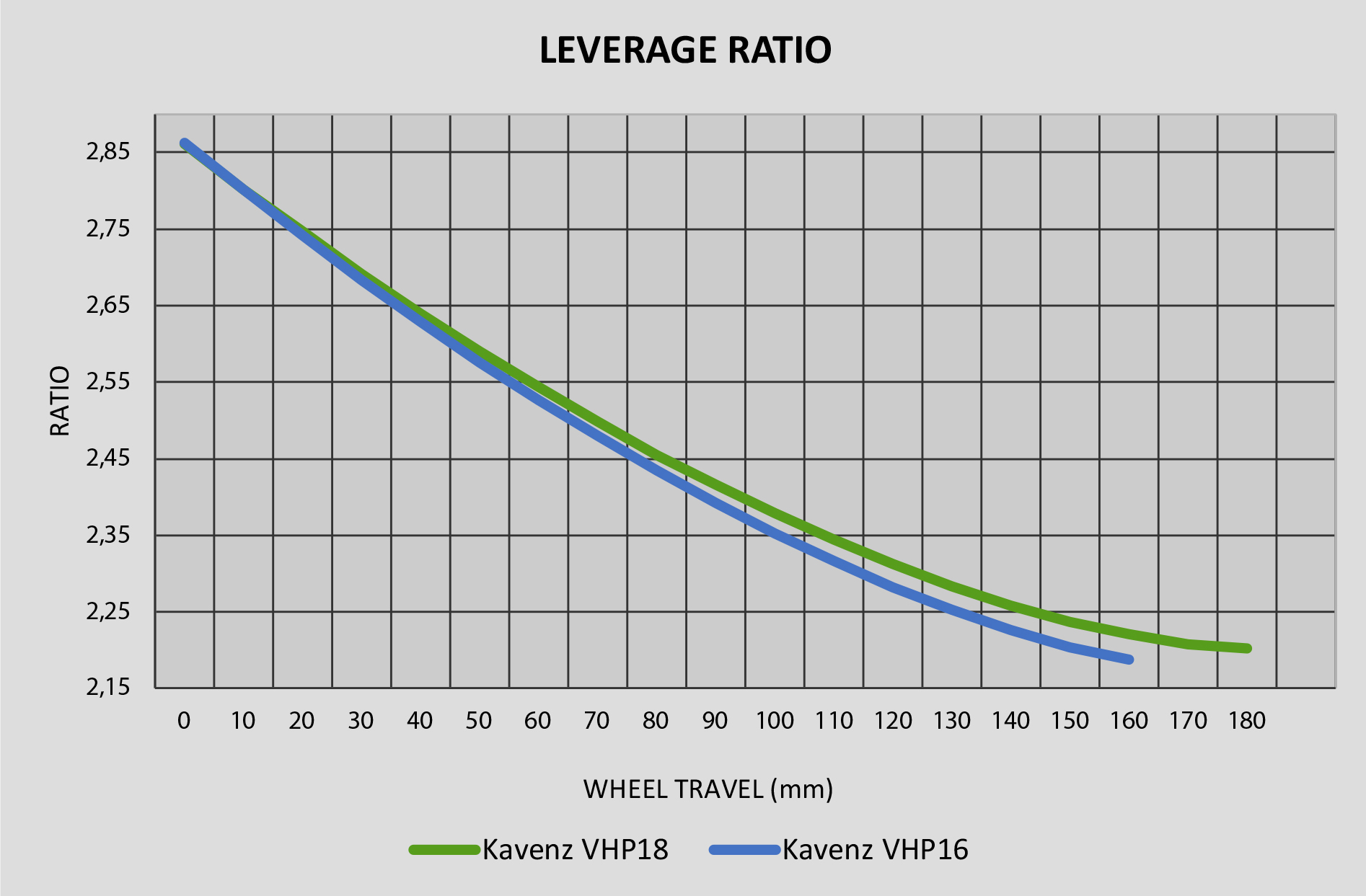

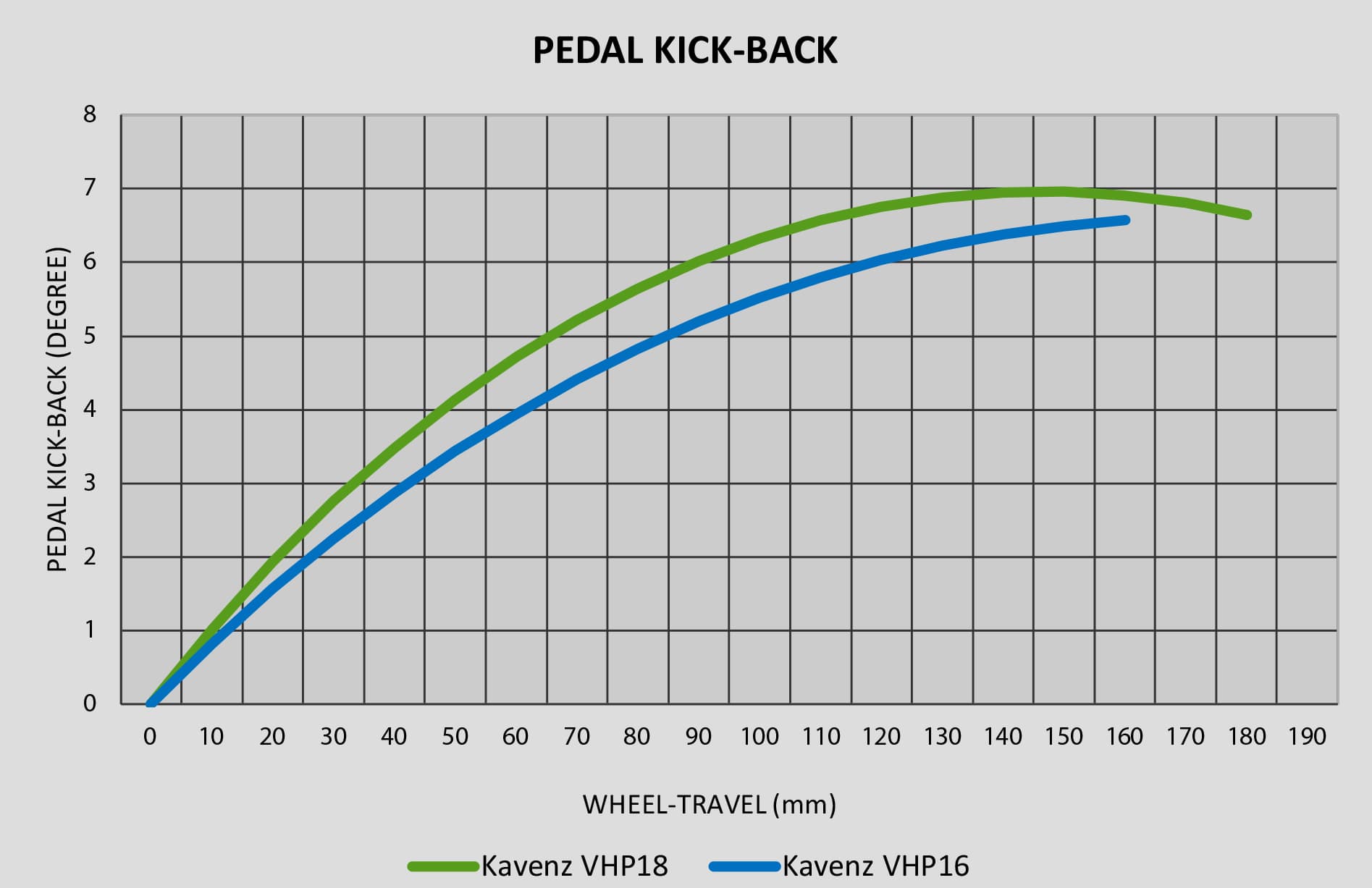

The VHP 16’s anti-squat is notably high, at around 140% near sag, and while there’s not a massive amount of pedal kickback (about 6.5° per Kavenz’s published graph), Kavenz also says that pedal kickback goes negative in the very highest gears. In short, Kavenz’s goal was to isolate the suspension from chain forces in the higher gears while still maintaining good pedaling efficiency in the lower ones. On paper, the results look super promising.

The leverage curve of the VHP 16 is quite progressive overall, going from about 2.85:1 to 2.2:1 in a reasonably straight line, though it does flatten out slightly near bottom-out. Kavenz offers the VHP 16 with both air and coil shocks and on paper, it looks like a frame that should worth well with either a coil or a relatively linear, high-volume air option.

[And if all of that suspension talk didn’t make much sense, check out the Suspension Kinematics section of our recently updated Mountain Bike Buyer’s Guide.]

The VHP 16 can be ordered in a raw finish (as seen on our test bike), black anodization, or in just about any color of powder coat you can dream up. The details are all fairly standard for this sort of bike — cable routing is fully internal, the bottom bracket shell is threaded (and features an optional splined ISCG-05 mount for a lower chain guide), and the brake mount is set up for a 203 mm rear rotor. As per usual for aluminum frames, that cable routing isn’t guided internally, but the VHP 16 uses snap-in ports to open up some bigger openings to make routing less of a headache, and Kavenz includes foam housing dampers to help keep things quiet. There’s no molded chainstay protection, but Kavenz includes a strip of mastic tape in the box to let you arrange your own.

Fit & Geometry

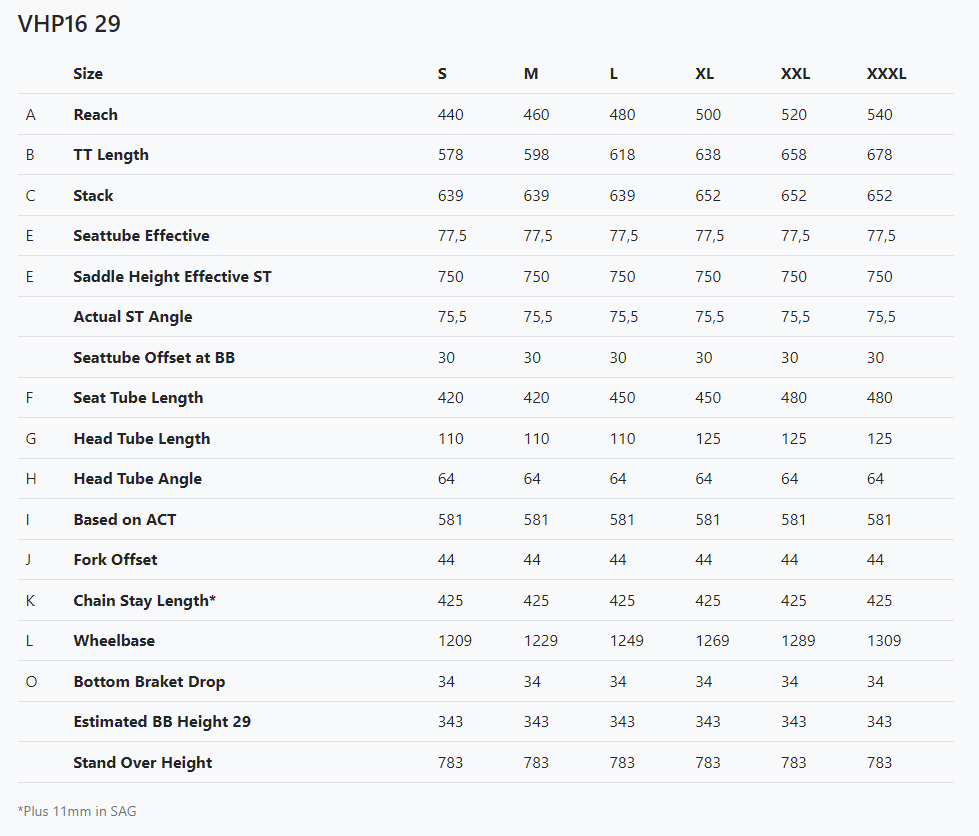

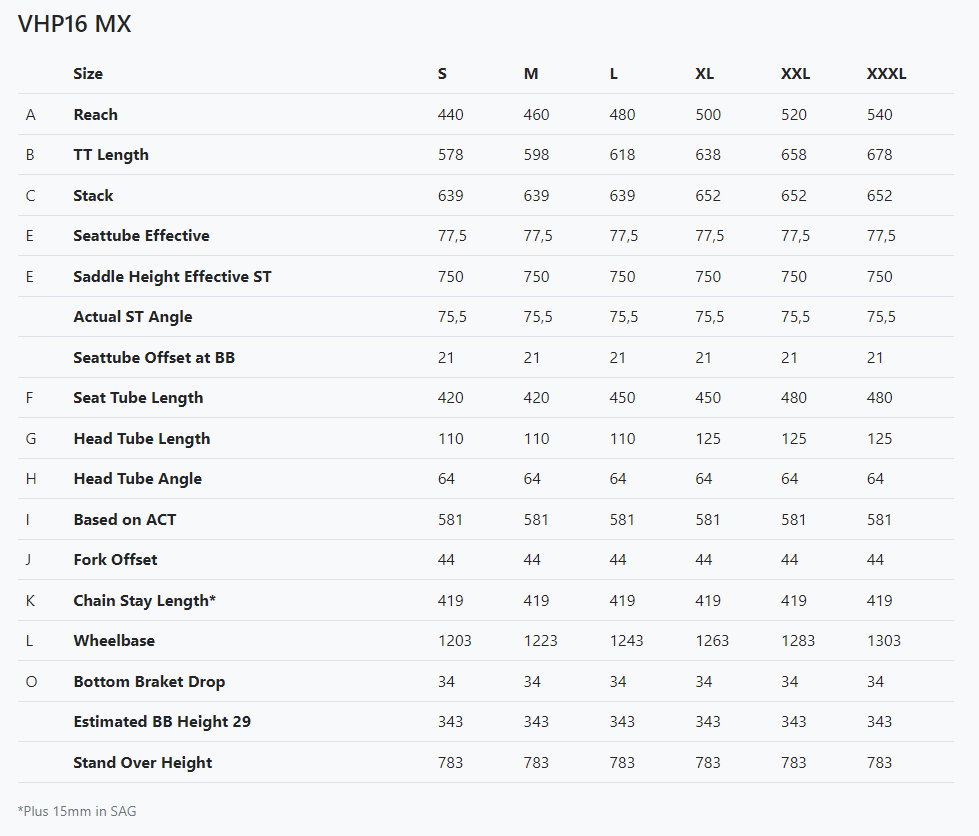

Kavenz doesn’t really do standard sizes; instead, the geometry is semi-custom. You can get a VHP 16 with reach anywhere from 440 to 540 mm in 20 mm increments, a 420, 450, or 480 mm seat tube, and your choice of a 110 or 125 mm headtube. Kavenz stocks a lot of the more common configurations but if you want a less-typical option (e.g. a very short seat tube with a huge reach) they’ll be happy to make that for you, and pricing is the same no matter how standard (or not) your combination is. Kavenz does list a geometry chart for the “standard” options but you can mix and match to your heart’s content.

The VHP 16 can be run as a full 29er or with a mullet (29’’ front, 27.5’’ rear) combination by way of a replaceable shock mount that keeps the geometry the same apart from a change in chainstay length — the 29er gets 425 mm static chainstays, and the mullet arrangement drops them to 419 mm. Both of those are very short by modern standards, but Kavenz notes that the high pivot layout means that the chainstays are about 11 mm (29er) or 15 mm (MX) longer at sag. They’re also working on an optional rear triangle with longer chainstays for folks who would prefer that, but the exact details aren’t available yet. And finally, the VHP 16 can also be converted to a VHP 18 — Kavenz’s 180mm-travel Freeride / Park bike — by swapping the lower shock mount and installing a longer 225 mm shock.

Regardless of which wheel size combination you’re running, the VHP16 has a 64° headtube angle, 77.5° effective / 75.5° actual seat tube angle, and a fairly low 343 mm estimated bottom bracket height (34 mm drop on 29’’ wheels). The VHP 16 isn’t wildly long or slack for a modern Enduro bike, but the numbers make a lot of sense given what Kavenz says about aiming for a balance between being fairly stable and capable in steep terrain and at speed, while also being a bit more nimble and playful than the most aggressive, game-on Enduro race bikes out there. The thing I’m most curious to see is just how short the 425 mm static chainstay length feels on trail — on one hand, that’s super short, but they do get substantially longer at sag, and the quite-steep seat tube seems like it should help mitigate some of the downsides of super short chainstays when it comes to traction and keeping the front wheel planted on steeper climbs. We’ve got a VHP 16 in for review, so we’ll have a lot more to say on that subject soon — and Blister Members can check out our Flash Review of the VHP 16 right now to hear our initial thoughts.

And speaking of our test bike, Kavenz recommended a 480 mm reach for me (6’ / 183 cm tall), and left the seat tube and headtube choice to me. I went with the 450 mm seat tube and 125 mm head tube, and while I think I could have made pretty much any combination with the 480 mm reach work, my early take is that this one feels great. Stay tuned for a lot more on that in the full review.

The Builds

Kavenz sent over a VHP16 frame for us to review, along with an EXT Storia shock for it. That left me to piece together the build with a combination of review parts and some old standbys. Kavenz doesn’t currently offer any complete builds but will sell the VHP 16 as a frame only, frame and shock package, or with a fork and/or dropper post included. Check out their website for the full list of options and pricing.

Review Build:

- Fork: RockShox ZEB Ultimate w/ Vorsprung Smashpot coil spring conversion (review coming soon)

- Shock: EXT Storia

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX

- Brakes: TRP DH-R Evo (223 mm front / 203 mm rear rotors)

- Wheels: Sun Ringle Duroc SD37 Pro

- Dropper Post: 9Point8 Fall Line, 200 mm (review also coming soon)

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) A lot of high-pivot Enduro bikes are meant to be super game-on and focused on flat-out speed, but Kavenz has targeted a more playful middle ground with the VHP16. How does that add up on trail? And who is that blend of traits going to make the most sense for?

(2) And how about the climbing performance of the VHP 16? High-pivot bikes generally give up some pedaling efficiency through the idler, but the VHP 16 has a ton of anti-squat, and manages to pair that with moderate pedal kickback in the lower gears (a combo that wouldn’t generally be possible with a more conventional suspension layout), which could be a super promising recipe for an excellent technical climber.

Flash Review

Blister Members can read our Flash Review of the Kavenz VHP 16 for our initial on-trail impressions. Become a Blister Member now to check out this and all of our Flash Reviews, plus get exclusive deals and discounts on gear, and personalized gear recommendations from us.

Bottom Line (For Now)

The Kavenz VHP 16 has a very interesting development story, having essentially begun as a kinematics study that eventually materialized into a full bike, and the end result is a super interesting blend of traits that aren’t often found together in the same bike. We’ve got a VHP 16 in for testing, so stay tuned for a full review soon.

FULL REVIEW

Intro

High-pivot bikes tend to be touted first and foremost for their ability to carry speed through rough terrain, and while the Kavenz VHP 16 does that fairly well, it’s a whole lot more versatile and less one-dimensional than just being a rock garden bulldozer. We’ve spent a ton of time on the VHP 16 this summer, and it’s not quite like any other bike we’ve ridden recently — in a way that should really click for the right riders.

Fit & Sizing

Kavenz sent over a VHP 16 frame with a 480 mm reach, 125 mm headtube, and 450 mm seat tube (check out our First Look, above, for more on their interesting semi-custom geometry program), and at 6’ / 183 cm, that combo fit me great. With the 125 mm headtube, the stack height is on the tall side, but I settled in on a 20 mm rise bar with 10 mm of spacers under the stem, so I still had ample room to go lower. And as we’ll get into more below, the VHP 16 worked best for me with a somewhat more upright, bars-high riding position, so the taller headtube felt like a good call.

I could have been happy with either the 420 or 450 mm seat tube option, still having ample room for a 200 mm dropper with the longer 450 mm one. Kavenz’s default “Large” frame has 480 mm reach, a 450 mm seat tube, and a 110 mm headtube, making the frame I tested slightly non-standard, though Kavenz has the version I tested in stock as well, at the time of writing this. It’s cool that Kavenz offers so many options for dialing in the fit for folks with less common proportions or preferences, along with some standard options for people who don’t want to get too bogged down in the minutiae.

Climbing

Given the widely varied experiences we’ve had with the pedaling efficiency of the different high-pivot Enduro bikes we’ve been on, I wasn’t sure what to expect from the VHP 16 on the way up. And I definitely didn’t expect it to offer as impressive a combination of really good efficiency and excellent compliance and traction under power as it does. The VHP 16 is above average in terms of pedaling efficiency for a 160mm-travel Enduro bike — high-pivot or otherwise — and still also maintains very good traction and stays reasonably active under power.

And that combination puts the climbing performance of the VHP 16 somewhere in the range of “good” to “great” (for an Enduro bike), depending on exactly what the climbs in question look like. If you tend to do a lot of grinding up fire roads or relatively mellow trails, the VHP 16 does pretty well. It’s reasonably efficient and its low-speed handling is calm and intuitive. But it’s when the climbs get rougher, tighter, and more technical that the VHP 16 really shines (again, by the standards of longer-travel Enduro bikes, which don’t tend to be the best technical climbers in general).

I’d credit a few things working together with the VHP 16’s climbing prowess. First and foremost, its suspension does an excellent job of being just active enough to maintain good traction while still being efficient enough to put down power effectively and stay up in its travel to help keep your pedals out of chunky bits. Its more compact dimensions and not-super-long wheelbase (again, by the standards of 160+ mm travel Enduro bikes) also help make the VHP 16 easier to maneuver at low speeds and loft up over things than a lot of big Enduro bikes.

The VHP16’s comparatively short chainstays probably help with rear-wheel traction by pushing the overall weight bias rearward, but the back end of the VHP 16 doesn’t actually feel that wildly short on the trail, which I’d largely credit to the substantially rearward axle path extending things significantly at sag. Between that and the steep seat tube angle, the VHP 16 didn’t give me much trouble in terms of keeping the front wheel planted on steeper climbs, either. Its 77.5° effective seat tube angle isn’t crazy steep, but given that the actual angle is only two degrees slacker, the VHP 16 feels pretty damn steep. Especially for an Enduro bike with comparatively short chainstays, I think that’s a good call, but it does mean that the VHP 16 wouldn’t be my first choice if I was going to pedal through a ton of rolling, mellow terrain. As soon as things pitched up slightly, the pedaling position felt great, but I’d personally prefer a slightly slacker seat tube for pedaling on flat ground, specifically. That’s obviously not what the VHP 16 is designed for, and again, I think the design feels sensible given the intentions of the bike, but the tradeoff is real.

As with every high-pivot bike I’ve tried to date, the VHP 16 does feel like its drivetrain efficiency falls off more quickly as the chain gets dirty and less well-lubed, relative to bikes with a conventional drivetrain layout. If things are clean and tidy, there’s a little extra noise from the idler, but nothing that feels noticeable efficiency-wise; once the chain starts to get dirty and shed lube, a little extra drag does creep in. I was somewhat worried that the small 14-tooth idler on the Kavenz would feel especially susceptible to that particular shortcoming, but that hasn’t proven to be the case — it’s in line with, but not appreciably worse than other high-pivot bikes.

I did notice a slight bit of heel rub on the seatstays of the VHP 16, particularly on the drive side. It wasn’t ever a major issue for me, but I also don’t have especially big feet (US size 10) and don’t typically have much trouble with heel rub on most bikes, so the fact that I noticed any at all is noteworthy. I don’t think most people will have much trouble, either, but if you’re especially susceptible to or bothered by a little rub, I might be a little warier.

Descending

First off, the suspension performance of the VHP 16 is excellent. It’s not what I would call ultra-plush, exactly — it’s quite supportive and composed, but pairs that with very good small-bump sensitivity off the top. And unlike some other high-pivot bikes that I’ve ridden recently (most notably the Forbidden Dreadnought), the VHP 16’s suspension also felt very consistent and predictable, without any notably weird behavior having to do with weight distribution moving as the suspension cycles or anything like that.

The VHP 16’s dramatically lower anti-rise compared to the Dreadnought, in particular, probably helps there, as does its less dramatically rearward axle path. Those were key parts of the suspension design priorities for the VHP 16 (check out Ep.117 of Bikes & Big Ideas for a whole lot more on that) and it worked. The VHP 16 just feels impressively intuitive right out of the gate, with very little of the quirky behavior that high-pivot bikes can display.

But the most impressive part of the VHP 16’s suspension performance is that it manages to be both fairly sensitive off the top, while still feeling supportive and composed when you start pushing it harder. Those traits tend to be somewhat in conflict with each other, but Kavenz has done an impressive job of creating a comparatively large window where the suspension feels really good. It’s often the case that setting a bike up to feel very supportive and composed when you’re pushing hard comes at the expense of small-bump sensitivity and plushness, or favoring compliance winds up making the bike feel wallow-y and unstable when you open up and start going harder. While those sorts of compromises still exist with the VHP 16, Kavenz has done a great job of designing a bike that can do both pretty well, at the same time / with the same settings.

All that said, the VHP 16 is definitely not the most lively, poppy-feeling bike — its suspension feels more planted and composed than eager to take to the air at every opportunity. But compared to a lot of other high-pivot bikes (the Norco Range being the first one that comes to mind), the VHP 16 feels more middle-of-the-road in that regard, rather than being as ultra-planted (or maybe ultra-dead feeling, depending on your perspective) as, say, the Range.

I did wind up preferring to run the VHP 16 with a 400 lb spring, over the 375 lb one that Kavenz suggested for my weight (170 lb / 77.1 kg), and especially once I’d bumped up the spring rate, the rebound tune on the stock EXT Storia did feel borderline too fast. I wound up running the adjuster one click from fully closed and was happy there, but it’d be nice to have a little more wiggle room to play with.

Its suspension performance is great, but what really makes the VHP 16 stand out is its combination of suspension and handling. Because while its suspension would probably still feel at home on a super long, slack, ultra-stable charger of a bike, the VHP 16 isn’t really that; by the standards of 160+ mm travel Enduro bikes, the VHP 16 is definitely on the quicker-handling, more maneuverable end of the spectrum. Of course, that’s comparing it to a class of bikes that is, as a whole, generally quite stable, and it’s definitely not like the VHP 16 turns into a twitchy mess when speeds pick up or anything like that. It’s just got a slightly smaller sweet spot to move around on the bike while still remaining composed than a lot of (generally longer, slacker) bikes in the category. This is particularly noteworthy when comparing it to high-pivot options that tend to have notably long wheelbases in a lot of dynamic ride situations where the suspension is compressed substantially, due to their rearward axle paths (and geometry that is otherwise designed to work in concert with the suspension).

But that’s not to say that the VHP 16 feels caught in between those two ends of the spectrum or anything like that — the combination of traits feels totally coherent and works together as a harmonious whole. It’s just not quite like any other bike I’ve ridden in recent memory. And so if you’re looking for an Enduro bike with especially good suspension performance — both when taking it easier, and when pushing the bike pretty hard — that doesn’t need to be going flat out all the time to come alive, the VHP 16 is a great call.

Given that, I had the most fun on the VHP 16 on trails that were fairly steep and technical, but a little too tight and twisty to qualify as being truly wide open and fast. There, its combination of excellent suspension + slightly quicker handling than most bikes with similar suspension performance worked great. And while 425 mm chainstays are, on paper, super short, they didn’t feel like nearly as much of an outlier on the trail — presumably in large part due to the VHP 16’s notably rearward axle path, which makes them more like 436 mm or so at sag. That’s more in the realm of “moderately short” instead of “very short,” and that’s how the VHP 16 feels on the trail — and it’s nicely balanced with the length of the front end, at least on the 480mm-reach Large(ish) bike that I tested.

When it comes to body positioning, the VHP 16 feels fairly neutral in terms of its preferred stance; if anything, it’s biased a little more toward sitting upright and centered vs. really getting over the front end, but not by a big margin. Bikes with shorter chainstays, and especially ones with short chainstays and longer front-centers can feel like you need to really stay over the front wheel to keep it gripping and stop it from pushing wide through corners, but that wasn’t my experience with the VHP 16. I think that’s mostly down to the stated 425 mm chainstay length being somewhat deceptive, due to the substantially rearward axle path. In most real riding situations they’re not as notably short, and that’s how they feel on trail. There’s still a limit to how far you can get off the back of the bike in flatter terrain before the front wheel loses traction, and the VHP 16’s sweet spot isn’t as huge as a lot of big modern Enduro bikes, but the VHP 16 doesn’t feel nearly as critical of body positioning as I thought it might, just based on the geometry chart.

Kavenz talks a lot about the VHP 16 being “fast,” and I think it could be a viable Enduro race bike for the right rider, on the right trails — particularly if quicker handling and ease of maneuvering in tighter spots is a priority — but pigeonholing the VHP 16 as a dedicated race bike sells it well short. It’s more versatile, more playful, and more fun if you’re not going flat out than the race-bike label would suggest, and therein lies the core of the VHP 16’s appeal, in my estimation: it’s a fairly versatile, very forgiving Enduro bike that can go hard if you want to, but really doesn’t need a super aggressive touch or high speeds to come alive, and there are plenty of folks out there for which that will work well.

The Build

Kavenz sent over the VHP 16 as just a frame and shock and doesn’t offer any complete bikes at the moment, so there’s not a ton to comment on here. I took the opportunity to use the VHP 16 as a test platform for a bunch of different review parts, including the new RockShox ZEB, Reserve 30|HD wheels, and TRP DH-R Evo brakes (review coming soon) — all pretty normal stuff for a long-travel Enduro bike.

It is worth touching on the overall fit and finish of the frame, though, because for the most part, it’s really nice. The pivot hardware, in particular, is especially high-quality and beefy, and the frame prep was nicely done as well. The VHP 16 is also surprisingly light — you’d be forgiven for thinking that an aluminum high-pivot frame is going to be portly, but Kavenz has done a nice job of keeping the frame trim (this particular implementation of a high-pivot layout doesn’t really add much material to the frame). The bare frame comes in at a pretty reasonable 3,357 g, including the rear axle, brake mount, and so on — nearly 600 g lighter than a similarly-sized Nicolai G1, for example.

The VHP 16 also uses a single commonly-available sized (9602) bearing throughout all of the suspension pivots, which is a nice touch to make service easier and keep the number of required spares to a minimum. All the pivots are easily accessible and straightforward to service (not that I needed to do anything to them in the 3.5 months that I spent with the VHP 16); it’s clear that Kavenz has put some real thought into making the VHP 16 easy to live with long term.

That said, my distaste for internal cable routing is well documented at this point, and I did find the Kavenz to be a significant headache in that regard — the combination of unguided routing plus fairly small openings in the frame meant that I spent quite a while fishing housing and hoses through the frame. Foam cable dampers (which Kavenz shipped with the frame) did a nice job of keeping things quiet, but also further complicated the routing. The frame ports at the headtube are also just open holes, with no covers or other gaskets to seal things off. It’s not a big deal, but feels a little crude, especially given the form-over-function call to route the cables internally.

The rear brake mount, which is tucked in between the seatstay and chainstay, also has the potential to make routing the brake hose somewhat awkward, depending on the brake in question. The TRP DH-R Evo that I ran on the bike worked nicely, due to its pivoting banjo bolt fitting, but brakes without the ability to pivot the fitting upward would make for a significant extra loop of housing. Kavenz says that most brakes should work on V6 frames going forward, but the routing might not be the cleanest, depending on the brake in question.

Comparisons

The Capra is probably the closest comparison here, but it’s still significantly different in a bunch of ways — kind of a testament to how uncommon the VHP 16’s ride is. They’re both long-travel Enduro bikes that feel especially easygoing and forgiving, while still being able to be pushed pretty hard. But the VHP 16 pedals quite a bit more efficiently, and the Capra is more stable at speed but correspondingly less nimble at lower speeds in tighter spots. The VHP 16’s suspension is also more supportive as you load it up through the pedals, whereas the Capra feels a little more plush / cushy in those scenarios.

The Gnarvana and the Capra remind me of each other quite a bit, but the areas in which they differ mostly push the Gnarvana further from the VHP 16. The Gnarvana is more stable at speed, a little less nimble in tight spots, and generally feels a touch more game-on than the Capra — which is to say that it’s substantially more stable and less nimble than the VHP 16. That said, the Gnarvana does pedal a bit more efficiently than the Capra (but not as well as the VHP 16), so it slots in as the middle bike of the three in that particular regard. The Gnarvana also works best when ridden with a slightly more rearward, upright stance than the VHP 16.

This one is interesting — both the 4060 LT and VHP 16 are pretty quick-handling, more playful takes on an Enduro bike, but they still don’t remind me of each other all that much. The VHP is more stable and composed at speed, and doesn’t feel nearly as far toward the “super playful” end of the spectrum for a 160mm-travel bike. The VHP 16 also pedals significantly more efficiently and is more neutral in terms of its preferred body positioning (whereas the 4060 LT specifically wants to be ridden with a fairly forward, aggressive stance with a lot of weight on the front end).

Super different. The Range is much more stable and composed at speed than the VHP 16, but also pedals much less efficiently, is way less nimble and playful, and generally feels much more singular in its focus as a go-fast Enduro / mini-DH bike. The Range is great at what it does, but it’s best summarized as the closest thing to a true DH bike that you can still pedal to the top (if you’re willing to put the work in). The VHP 16 isn’t as interested in being fully pinned all the time, but it’s easier-going, more versatile, and a lot more fun and engaging if you’re not pushing it very hard on something steep and rough.

Also way different. The Jekyll and the VHP 16 are the two most efficient pedaling high-pivot bikes that I’ve been on to date (and aren’t far off from each other in that respect) but there are few similarities beyond that. The Jekyll is more stable at speed, doesn’t offer as good small-bump sensitivity, and generally feels like a more high-strung, focused bike that primarily wants to go fast first and foremost. The VHP 16 is happier taking things easy — while still being able to be pushed pretty hard, too.

Super different. The Dreadnought is more stable in a straight line and better at bulldozing everything in its path, but is also more sluggish at lower speeds, even less poppy and eager to take to the air than the VHP 16, and I found the Dreadnought to corner less intuitively and be quite demanding in requiring the rider to conform to its preferred cornering style. The VHP 16 is also more efficient under power and its rear suspension is much more composed and active under braking, whereas the Dreadnought settles much deeper into its travel (it’s got a ton of anti-rise) and firms up significantly when the rear brake is engaged.

These two feel somewhat similar in terms of how they handle but are very different in terms of suspension performance. Both are on the quicker-handling side of the spectrum, as far as Enduro bikes go, but if anything the Rallon feels a little sharper and more precise. The VHP 16’s suspension is much more plush and composed, but correspondingly less lively and energetic. And while the VHP 16 pedals notably well, the Rallon is more efficient yet.

Put differently, the Rallon excels when it’s been ridden very precisely and dynamically, whereas the VHP 16 is more forgiving of sloppier line choices and lazier riding, but isn’t as ultra-precise and sharp handling as the Rallon.

The Firebird and VHP 16 are both notably quick-handling Enduro bikes that are still reasonably stable in a straight line, but that’s about it in terms of similarities. The VHP 16’s suspension is more compliant and offers more rear-wheel traction, whereas the Firebird’s is more firm, supportive, and lively. The Firebird is also a little more stable, doesn’t pedal quite as efficiently, and generally needs to be pushed a bit harder to come alive, but feels more fully in its element once you do. While it could definitely serve as one, the VHP 16 doesn’t really scream “EWS race bike” to me; the Firebird does.

Like the Pivot Firebird, the Megatower feels more specifically focused on going fast than the VHP 16 does, but it goes about it fairly differently. The Megatower is more stable, more planted in its suspension performance, and less lively and agile than the Firebird. Compared to the VHP 16, the Megatower is much more stable and is yet more planted to the ground / less lively feeling. The VHP 16 pedals more efficiently and is more nimble and engaging at lower speeds.

Super different. The G1 is way more stable at speed, but also slower handling and more work to muscle around in tighter spots. The G1’s suspension is both more lively and less sensitive off the top but does start to come alive more as you push the bike harder. Both pedal very well for what they are, and there’s not much to separate the two when it comes to climbing efficiency, but the VHP 16 is more maneuverable and less of a handful when the climbs get tighter and more technical.

Basically, the G1 is a more game-on, demanding bike that’s more composed and confidence-inspiring when going really fast, but is less versatile, less engaging when you’re not going flat out, and quite a bit less nimble at lower speeds and in tighter spots.

Who’s It For?

The VHP 16 offers an unusual blend of traits, but one that I think is going to work especially well for the right riders. Specifically, folks who spend a lot of time riding steep, technical, more natural trails — especially ones that aren’t super wide-open and fast — are going to find a lot to like here. The VHP 16 isn’t quite as stable at speed as a lot of (generally longer, slacker) Enduro bikes and is more planted and composed than it is lively and poppy, so folks who are looking to double up and boost off every little feature they encounter might find it slightly dead feeling. But if you’re looking for a bike with suspension that feels both forgiving and composed when things get rough, packaged into a bike that’s sharper handling than a lot of stuff with similar suspension performance, the VHP 16 should be on your radar.

Bottom Line

The Kavenz VHP 16 is a unique bike in a lot of ways, from the story of its development to its made-in-Germany construction and semi-custom geometry, but especially in its combination of disparate ride traits that it manages to blend into one coherent, well-thought-out whole. It’s a relatively playful, quick-handling high-pivot bike, one that blends outstanding suspension performance (whether or not it’s being pushed particularly hard) with good pedaling efficiency and climbing prowess, and there aren’t many other bikes like it. The VHP 16 does give up some straight-line stability compared to a lot of other bikes with similar travel numbers, but if you want a long-travel bike and the suspension performance that comes with it, but find a lot of ultra-long modern Enduro bikes to be too sluggish at less than full throttle, the VHP 16 just might be the ticket.

Nice, I’ve got one of these and it’s been a blast. I was worried it would feel glued to the ground and not playful, but it’s been surprisingly fun to jib around with and easy to manual / bhop. This is with the Storia. Of course, it still loves to plow and is very supple.

Now that I’m sitting out for a bit with a fractured collarbone (no fault of the bike!), I picked up a cheap Float X and am going to experiment with air suspension in various travel configurations once I’m back riding. 205×60 should give 150mm of travel and make things more poppy. If it works well I may swap between them depending on what I’m feeling.

I love the Kavenz. It my favorite bike I’ve ever ridden or owned. Whether I’m riding bike park laps or super steep loamers the bike just rips. It’s the first frame I’ve owned in a long time that I’m planning to keep more than a year.

Excellent article qui résume parfaitement bien le bike. 32 ans de riding, mon meilleur vélo. Stable, maniable à basse vitesse, une tonne de grip (en float X2), grimpeur hors pair, pardonne bien des erreurs, et la possibilité de choisir une partie des spécifications. Il enterre les marques commerciales aux caractéristiques figées, et son poids reste contenu même en comparaison de bon nombre de cadres carbone. Giacomo a fait un excellent boulot, ceux qui hésitent peuvent se lancer les yeux fermés!

I have no recollection of taking that last photo

Is it safe to assume the VHP16 is a better technical climber than the Rallon despite the Rallon being the more efficient pedaler?