Nicolai / Geometron G1

Wheel Size: 27.5’’, 29’’, & Hybrid 29’’ / 27.5’’

Travel: 162 / 175 mm rear; 160–190 mm front

Material: Aluminum

Blister’s Measured Weight:

- Frame only (including axle and seat post clamp, size Medium / “Longer”): 3,929 g

- EXT Storia shock (including spherical bearing mounting hardware): 466 g

- 375 lb spring: 291 g

- Total: 4,686 g / 10.33 lb

- Complete bike, as built: 16.0 kg / 35.3 lb, w/o pedals

Price:

- Frame and EXT Storia shock: £3,290 / $3,770

- Complete bikes: £6,250 – £7,750 / $7,160 – $8,880; custom build options also available

[Note: UK prices include 20% VAT; US dollar prices are without VAT, at the conversion rate at the time of publishing.]

Reviewer: 6’, 170 lb / 183 cm, 77.1 kg

Test Location: Washington

Test Duration: 9 months

Intro

Chris Porter has long been known for pushing the envelope of what mountain bike geometry could be and he blew a lot of minds around the bike world when, in collaboration with Nicolai, his company Mojo put the first Geomotron on the market back in 2015. That bike soon became known as the G16, and I’ve owned one as my personal ride since 2017. That project soon spawned Geometron Bikes — the spinoff of Mojo (still run by Chris) that develops and distributes the bikes, with Nicolai continuing to handle production.

The G1 is their follow-up to that original G16 (which itself went through a few small revisions over the years). The overall design and layout are similar, but the geometry has been refined, some details tweaked, and a great deal of adjustability added — for both geometry and wheel size, as we’ll describe more below.

All of that adds up to a bike that somehow doesn’t stray too far from its predecessor, and yet still stands out in the market more than six years later. I’ll be spending a lot of time on the G1 to see how it compares to the G16 and the rest of the market, but in the meantime, we’re going to dive into the design of the G1 and what makes it so interesting.

The Frame

Nicolai has built a reputation for their aluminum construction and the G1 sticks to that tradition. There’s no carbon option, and Nicolai’s trademark giant welds are featured front and center. As with the G16, the G1 is available from either Nicolai directly or from Geometron. All the frames are made by Nicolai regardless of who handles the distribution, and both versions of the frame are identical apart from decals and some very minor finishing touches that we’ll describe in more detail below.

As with all of Nicolai’s bikes, they’re made in Germany with the machining, welding, finishing, and assembly done in house. The G1 frame comes with “MADE IN GERMANY” proudly etched into the non-drive-side chainstay. And they’re right to be proud of the craftsmanship — the machining and welding on display are outstanding, and the fit and finish are truly second to none.

The G16 was already a beefy frame, but the G1 takes things a step further; the downtube is larger, the seat tube has thicker walls, and some extra gussets have been added to further reinforce things. The G1 is rated for use with dual-crown forks up to 596 mm axle-to-crown height, and up to 40mm-diameter stanchions. That (narrowly) rules out a full 29’’-wheeled, 203mm-travel Fox 40 and Manitou Dorado, as well as a 200mm-travel RockShox Boxxer, but all are viable once lowered to 190 mm.

The overall layout of the G1 frame hasn’t changed much from the G16 and still features a Horst-link suspension design, with a horizontally-oriented rear shock that unfortunately doesn’t leave room for a water bottle. The G16 could be converted between 155 and 175 mm of rear-wheel travel, but doing so required both reversing a flip chip and changing between two sizes of rear shock. The G1 slightly narrows the spread between the two travel options to 162 and 175 mm, but achieves both with the same size shock and the reversal of a chip on the rocker link. Since switching travel configurations changes the overall leverage ratio of the bike, Geometron says a change of spring rate will be required and recommends running a 25lb heavier coil in the 175 mm setting. The EXT Storia rear shock that the G1 is designed around comes stock with two spring weights, and Geometron will help you choose the most appropriate weights — recommending 350 and 375 lb options for me, at ~165 lb / 74.8 kg

Speaking of the shock, the G1 gets a special version of the EXT Storia that’s a bit different from the standard version. The G1-spec version adds a coil negative spring for even greater small-bump sensitivity, and spherical bearings in both eyelets to reduce friction and binding. I spent a lot of time with a “standard” Storia (which still features a custom damper tune) on the G16, and will be very curious to see how the tweaks made for the G1 impact its performance.

The G1 features a standard threaded bottom bracket, 148 mm Boost rear end, and external routing for the brake hose and derailleur housing. The rear brake mount is set up for a 180 mm rotor, and Nicolai condones running up to a 203 mm with an adapter. The dropper cable is routed internally through the downtube, entering through a bolt-on port on the right side of the downtube. There are two options for the exact style of external routing for the brake and derailleur lines; the “Geometron” spec version uses bolt-on guides on the outside of the shock and rocker link mounting tabs (as pictured); the Nicolai-spec style routes them inside of those tabs, and therefore requires disconnecting the brake hose to run it underneath the rocker link pivot. This arguably looks slightly cleaner, but also negates much of the convenience of external routing. Either style of clamps can be ordered from either Geometron or Nicolai; just ask if you’d rather change from their default.

The G16 already featured adjustable chainstay length by way of switching out the dropout pivot housings (Nicolai / Geometron call them the “chainstay mutators”) for different length options, but the G1 adds a similar arrangement to the seatstays. In short, you can bolt varying thickness of spacers between the ends of the seat stays and the rocker link pivot housing (shown below with no spacer installed), which in conjunction with the chainstay mutators offers a dizzying array of geometry and wheel size options. The G1 can be run 27.5’’ front and rear, 29’’ front and rear, or with a hybrid 29’’ front / 27.5’’ rear setup, with a multitude of geometry options in each. We’ll discuss those in more detail in the “Fit & Geometry” section, below.

If all those options aren’t enough, a G1 can be ordered with a raw aluminum frame, one of several colors of anodized finish, or just about any color of powdercoat that you can imagine. The rocker link and other small parts can also be had in a wide range of anodized colors for an upcharge; a raw frame with black hardware (as shown here) is the default, but the sky’s the limit for customization if you so choose.

Nicolai offers a 5 year warranty on G1 frames for the original owner, and guarantees small parts availability for 10 years from the time of purchase. In addition to the extra-beefy construction described above, there are tons of little features built into the G1, with an eye towards durability. The rear brake mounts feature replaceable steel barrel nuts for the threads, so they’re both harder to strip and easy to swap out if you do; similarly, the seatstay mutator bolts thread into steel inserts, rather than being tapped directly into the swingarm. The same goes for the lower two mounting holes on the ISCG-05 tabs. All the pivot hardware features excellent secondary sealing, and I haven’t had to replace a single pivot bearing in four years of G16 ownership, despite living in the Pacific Northwest and riding year-round.

Fit & Geometry

Even in our current world of longer / lower / slacker everything, the G1 is still notably aggressive. It’s even more remarkable when you note that it’s actually not too far off the geometry of the old G16, which debuted all the way back in 2015 — ages, in terms of the evolution of mountain bike geometry. The headtube angle is the same; the reach has actually shrunk by 5 mm on my size Medium frames, and the seat tube angle is only about a degree steeper. All of that says a whole lot more about just how revolutionary the G16 was when it first came onto the scene than it does about the G1, though — as we’ll get into here, it still takes the longer / lower / slacker trend further than just about anything else out there.

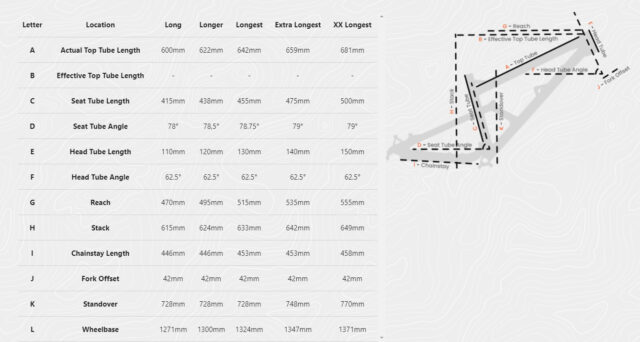

The G1 is offered in five sizes, which Nicolai labels Small through XXL; Geometron labels them “Long” through, hilariously, “Extra Extra Longest.” They’re not wrong though. Even the Small / Long frame has a 470 mm reach; my Medium / Longer comes in at 495 mm, and the subsequent sizes each add 20 mm, culminating in an absolutely gargantuan 555 mm on the XXL. The headtube angle sits around 62.5° in all five sizes, and the effective seat tube angle ranges from 78° to 79°, getting steeper as you move up the size range. Chainstay lengths start at 446 mm on the Small and Medium, and grow to 453 mm on the Large and XL, before jumping to 458 mm on the XXL. All of that adds up to wheelbase numbers ranging from an already very-long 1,271 mm on the Small, through 1,371 mm on the XXL. I haven’t run the numbers to confirm but I think that might be longer than my truck. The full geometry chart can be seen below:

Or at least, those are the “default” numbers. As we mentioned above, the G1 is quite possibly the most adjustable frame out there, from a geometry perspective. By swapping the chainstay and seat stay mutators, you can set any size G1 up with any of the possible chainstay lengths in the range, and/or significantly steepen or slacken the overall geometry — to say nothing of the wheel-size flexibility that they also afford. The options are so complex that Nicolai and Geometron maintain massive spreadsheets with the full slate of options. If you really want to take a deep dive you can check out Geometron’s, here. And if that somehow isn’t enough options for you, Nicolai can also make a G1 with fully custom geometry for an upcharge.

All of that is to say that the G1’s geometry is… aggressive. Reach numbers aside, it’s no longer wildly out of line with some of the other most progressive bikes on the market (the Transition Spire is notably similar) but the reach on the smallest G1 is still between that of the Medium and Large Spire. Geometron says that their range of sizes covers riders from 5’5’’ through 6’9’’ (164–205 cm), but are also quick to note that sizing isn’t as prescriptive as just matching a height to a frame size. Riding style and preferences go a long way, and the G1 is one of the few bikes that I’m tempted to downsize on. At 6’ / 183 cm, the Geometron size chart would actually put me on a Large / Longest frame, but my experience on my Medium / Longer G16, plus a quick spin on a Large G1 convinced me that bumping down for a little extra maneuverability was the way to go. I definitely could ride a Large, but the G1 is already a very long, very stable bike, and my hunch was that I’d rather size down and preserve a little more playfulness.

The Build

Nicolai and Geometron predominantly offer the G1 as a frame-only package or as part of custom builds, but Geometron does list a couple of stock options on their site, with the possibility to customize them to your liking; Nicolai’s site offers a comprehensive bike builder tool to spec your G1 exactly as you wish. Partial builds are also available.

I got my G1 as a frame / shock package from Geometron, which also includes a Hope headset and seat post clamp. I then built it up with the following:

- Fork: Manitou Mezzer Pro, 170 mm

- Shock: EXT Storia

- Drivetrain: Shimano XTR

- Crankset: Hope Evo

- Brakes: Hayes Dominion A4

- Wheels: We Are One Union rims / Hadley hubs

- Dropper Post: OneUp V2, 210 mm

All that adds up to a complete bike weight of 35.3 lb / 16.0 kg, without pedals. The G1 frame isn’t light, and the build philosophy was clearly meant to emphasize downhill performance first and foremost, and then save weight where practical, without compromising performance or durability. The result is on the heavier side for a high-end Enduro bike, but I’m really not bothered by that. As we at Blister have talked a lot about recently, weight matters a lot more on bikes that are meant to perform on more mellow, rolling terrain, and the G1 is not that. This is a bike and a build that’s meant to descend aggressively first and foremost, while still being able to pedal back up to the top.

Some Questions / Things We’re Curious About

(1) Just how different does the G1 feel from the G16 that it effectively replaces, especially with both bikes in a full 27.5’’ wheel configuration? And how does the special version of the EXT Storia on the G1 play into that?

(2) How does the G1 stack up to the current crop of super aggressive Enduro bikes, which have been creeping closer and closer to Geomotron geometry numbers for a while now?

(3) How will all the wheel size experiments shake out? It’s rare to be able to try all three “normal” modern combinations on the same bike, and we’re very curious to find out more.

Bottom Line (For Now)

The Nicolai G1 is one of the most aggressive Enduro bikes on the market — despite having been around for a few years itself, and being heavily based on a model that debuted way back in 2015. After four-plus years on the G16, I’m very excited to give its successor a go and to experiment with the litany of wheel size and geometry adjustments it affords. Stay tuned for a full review to come, along with some more experimentation with wheel sizes, geometry, and a whole lot more.

FULL REVIEW

I bought my first Geometron in 2017, and at the time, that G16 seemed wildly aggressive — a 62.5° headtube angle and a reach over 500 mm were unheard of back then. It didn’t take me long to come around to what they were doing, even if the bike never stopped turning heads in the parking lot. But times have changed, and there are a whole lot more bikes with similar numbers these days. Nicolai and Geometron rolled out their update to the G16, the G1, a few years ago, and it’s much more of a moderate update than a dramatic overhaul — but the changes are (with one very minor exception) for the better.

You can hear a whole lot more about the G1’s development process and the thinking behind it in Episode 80 of Bikes & Big Ideas, where I sat down with Chris Porter of Geometron Bikes to get the rundown on the G1 (and a whole lot more). And with that, let’s dive into my impressions of the bike.

Fit & Sizing

I’m 6’ (183 cm) tall and tend to like pretty long bikes. And yet I’m riding a Medium G1. On most bikes, if anything, I’m choosing between a Large and XL, but not here. Geometron’s recommended sizing would steer me toward a Large, but they also say that those suggestions are just a starting point and that folks should size up or down as appropriate, based on their personal preferences and riding style.

I have ridden a Large G1 very briefly, and I could definitely make it work — it’s not like I don’t fit on it, despite the somewhat dizzying 515 mm reach. But mostly, I just don’t need a bike that’s that stable. My home trails are mostly very steep, with a fair number of high-speed sections, but it’s not like I’m riding wide-open stuff in, say, Finale, either.

Especially compared to the G16, I think Nicolai and Geometron have done a good job of making the G1 a bit more flexible in terms of sizing, and making it easier for a lot of folks to size up or down. The steeper seat tube angle (and correspondingly shorter effective top tube) is a big part of that, as is the taller stack height. On the G16, I already felt like the effective top tube was borderline long on the Medium frame, and that limitation, much more so than the reach / standing cockpit length, would have stopped me from sizing up to a Large. But the stack height was also already a bit shorter than I would have considered ideal, making the Medium frame feel like the clear right size by default — more because the other options were too compromised in one way or another.

The G1 feels significantly easier to work with on that front. The stack height is substantially higher, which is welcome (but still on the low side — so folks who want to size up have room to do so) and the effective top tube isn’t nearly as huge as the 495 mm reach would suggest. And on that note, I think they’ve nailed the seat tube angle. It’s quite steep, at 78.5° (effective), but isn’t so over the top that it feels particularly awkward when pedaling around on flatter ground, either.

I think a lot of folks are used to thinking of Geometrons as having completely insane geometry, and it’s true that there wasn’t anything else like them five years ago. But a lot of the bike world has caught up — for example, the Transition Spire has the same headtube angle (62.5° in the low position), slightly longer chainstays, and an only slightly slacker seat tube angle. The size range is different, granted — my Medium G1 has a reach between the Large and XL Spire — but nobody bats an eye at a Spire at the trailhead, and if you don’t worry too much about the nominal sizing and just go with the G1 that works for you, it’s really no more out there.

Now, the fact that the Small G1 has a 470 mm reach is definitely going to rule it out for some shorter folks. Geometron’s recommended sizing suggests the Small for riders down to 5’5’’ (164 cm) and I do think that at least some people that height could happily ride a G1 if they want a notably long, stable bike. But it would be nice to see an XS in the lineup. On the flip side, The G1 caters to the very tall end of the bell curve better than just about anything else out there — if you want an XXL frame with a 555 mm reach, Nicolai / Geometron have you covered. There probably aren’t a ton of people who need a bike that big, but it’s awesome that the option is there, and those riders don’t have many similar options from other brands.

Climbing

A lot of people who I’ve spoken to about the G1 assume that it’s going to be a terrible climber, but it’s actually on the more efficient side of the spectrum for a 170+ mm travel Enduro bike. The pedaling position is great, and the G1 truly puts power down better than most bikes in this class. It’s not as all-out efficient as the Privateer 161, but the G1 isn’t too far off, and it both maintains traction better when things get rough, and feels a whole lot more natural in terms of pedaling position if the climb isn’t super steep. When grinding up a fire road or relatively mellow climbing trail, the G1 does great for what it is.

That said, technical climbing is definitely not the G1’s forte. The quite-long wheelbase makes it a bit of a handful to work around very tight switchbacks, and the combination of the wheelbase and notably low bottom bracket (especially in my preferred geometry configuration; more on that below) does make things tough when trying to lift the bike up steep ledges and the like. The G1 isn’t very maneuverable at those kinds of speeds, pedal clearance is a bit limited, and the long wheelbase makes the bike harder to hop up ledges and other stair-step-y climbing features. Now, I think that’s a fine tradeoff for what the G1 can do on the way back down (and if you’re buying this sort of bike for its technical climbing prowess, you’re pretty far off the mark). But it’s undeniably a tradeoff that you get with this kind of geometry. And like anything at the slacker headtube angle end of the spectrum, the G1 does take a little care to keep the front end from wandering on climbs, though the steep seat tube and comparatively short effective top tube definitely help there. Keeping the front wheel planted takes almost no effort at all, but the steering does feel a bit floppy at very low speeds, especially with less weight on the bars.

The climb switch on the stock EXT Storia isn’t especially firm (nor is it as soft as that on the Fox Float X2 or DHX2) but it does make some difference. Between the G1 not needing a ton of help on that front, and the switch not being especially effective, I haven’t found myself using it all that much. When the time comes to send it in for service, I’m inclined to ask about the possibility of firming up the tune on the climb switch, but haven’t yet inquired about what’s possible there. But since each Storia is custom tuned from the factory based on rider weight and preferences, it might be worth asking about a firmer climb mode if you think that’s something you might prefer.

Descending

The G1 isn’t a bike that’s all that interested in being ridden lackadaisically or taking it easy — it’s very stable, favors a relatively firm, supportive suspension setup, and isn’t particularly maneuverable at lower speeds. It also works best when being ridden with a fairly aggressive, forward stance to keep the front wheel gripping. If you get sloppy and too far off the back in flatter spots, the front can definitely start to push, but get forward and push through the front of the bike and it all starts to click.

But all that said, I don’t think you need to be an exceptional rider to get a lot out of the G1. It’s not a bike that I’d recommend to most beginners, but I think it could be a good option for the right high-intermediate riders and up — with the biggest key being that it’s a bike for people who have access to steep, sustained descending, and want to focus on tackling those descents quickly. There are probably more expert riders in that camp than intermediates — and again, if you want a bike that can do all that pretty well and is also happy taking things easier, there are definitely better options. But if your approach is suitably aggressive, you certainly don’t need to be a pro-level rider for the G1 to be a great fit.

And in at least some respects, the G1 is actually quite forgiving. To reiterate, it doesn’t favor especially plush, cushy suspension setups, and isn’t the best option if you want a bike that’s going to mute out every little bit of trail feedback. But most bikes that iron out the trail almost completely also get a bit wallow-y and soft feeling when speeds pick up and you start hitting stuff harder, and that’s where the G1 excels. Between its roomy cockpit, long wheelbase, and well-sorted, supportive suspension, the G1 affords a ton of room to move around on the bike, soak up impacts, and correct for mistakes. And so from the perspective of looking for a bike that helps you push hard and really try to charge wherever possible, it’s very forgiving, and adds a significant margin for error when you’re riding at or near your limits.

The key to all that, though, is that you do need to be pushing the G1 a bit for it to all start to come together. If you’re riding tentatively and off the back of the bike, it can start to feel stiff, ponderous, and rather demanding. It’s a bike that takes some commitment and aggression from the rider to start to work, but rewards that with a ton of capability and stability at the top end. And especially as you start going faster and hitting things harder, there’s excellent support from the suspension to keep the bike from pitching back and forth, particularly through very rough, hole-y sections of trail.

The G1 also corners very well once it’s up to a bit of speed — at very low speeds, where you’re primarily having to turn the bars to steer, it does feel long and a little unwieldy. But once you’re going quickly enough to really lean the bike in, it all starts to click. There’s a ton of grip and a big window to move around on the bike and weight the wheels as you need to without upsetting its balance. The notably low bottom bracket (more on that in the Mutators & Wheel Sizes section, below) also accentuates the feeling of being “in” the bike and being able to lean it over and carve through corners hard. If you want to unweight the rear to slash it around, it does take a significant shift forward, but there’s so much room to work with that the balance point doesn’t feel like a tiny window you have to hit.

The braking characteristics of the G1 are also very good — it does a nice job of staying fairly active, with moderate anti-rise (~65% at sag, falling off deeper in the travel) that’s just enough to keep it reasonably neutral and keep the bike from pitching forward too dramatically. As someone who tends to like braking fairly hard and late when I can get away with it, the balance that the G1 strikes there is excellent.

The Build

Well, there hasn’t really been the build. A big part of the G1’s job in my stable is to serve as a testbed for a wide range of different parts, and it’s already been through five different fork setups, three sets of brakes, multiple wheelsets, a couple of rear shocks, and so on. And since the G1 is a bike that I think most people will buy either as a frame or with a fairly custom build, I’m not going to go too deep on how I built up mine. Mostly, it’s a big, stable bike that carries speed quite well, and I think that most folks who are going to be well served by a G1 with any build will mostly want to opt for a fairly burly, downhill-oriented set of parts. In particular, go for a stiff fork — the very slack headtube angle makes differences in fork stiffness, especially fore-aft, significantly more pronounced than they are on more moderate bikes.

I also think that the G1 works significantly better with a coil shock, even compared to an air shock with a fairly high-volume, linear air can. The new 2023 RockShox Super Deluxe that I’ve been testing on it of late is excellent, but the G1’s leverage curve is just so progressive that a coil shock feels better suited — and that’s probably no great surprise, seeing as it was designed around the EXT Storia coil shock. That’s no knock against the Super Deluxe Air (and I’m quite excited to try the coil version out soon), but the more progressive air spring either results in a bit less midstroke support (if you run slightly less air pressure) or an overly firm ramp-up deep in the travel that feels a little harsh and makes it nearly impossible to use full travel if you firm things up to get the midstroke support. Unless you’re very sure that you want an exceptionally progressive setup, go with a coil. The SuperDeluxe air also only clears the G1’s linkage in the 162 mm travel setting — 175 mm mode is a no-go.

The stock EXT Storia that the G1 is designed around is extremely impressive. The first iteration of that shock that I tested on my G16 a while back was already outstanding, but the addition of spherical bearings in the eyelets and a coil negative spring (check out “The Frame” section, above, for more on that) make a real difference, particularly in terms of initial sensitivity off the top. While the G1 / Storia combo doesn’t feel especially plush and cushy, it does break away and start moving extremely smoothly, and the resulting traction from the rear wheel is excellent. It feels fairly firmly damped and much more supportive than plush, but it’s also super smooth and sensitive.

The coil negative spring does make setting preload on the Storia a little strange. In short, there’s a fine balance to be struck between not preloading the negative spring too much and producing a bit of topout clunk, and not accidentally setting too little preload and having the spring come loose and rattle once the rear wheel is unweighted and the negative spring compresses a bit under the weight of the rear end of the bike. And because the forces are so nicely balanced at topout by the negative spring, it’s not always super obvious where in that range you are, especially if you’re trying to do it with the shock in your hand, unmounted from the bike. I found it easiest to set with the shock mounted and the bike in a stand to unweight the rear wheel. Even so, it took a little trial and error to land on settings that didn’t settle into doing something a little off after a few minutes of ride time, but fortunately, it’s a set-and-forget situation as long as you’re not changing spring rates.

It’s also worth calling out the impressive build quality on the G1. The fit and finish on all the parts and hardware are top-notch, and the secondary sealing on all the pivot hardware is excellent. Nine months isn’t the longest-term test, but my G16 (which uses the same design for all the pivot hardware) made it through four-plus years of riding (including through PNW winters) without needing any of the pivot bearings replaced, which is remarkable. And despite the added complexity of the Mutator system, I’ve had no issues with creaking or other such issues on either bike. The only major shortcoming is the stock chainstay protector, which doesn’t have nearly enough coverage to keep things quiet. I initially sorted that out with liberal application of mastic tape, but eventually switched over to trying the STFU Bike protectors, which have also been super effective.

The internal routing for the dropper post is also mildly irritating. Routing the cable was easy enough, but it’s unguided through the downtube and it took some experimentation to figure out how to stop it rattling. Foam dampers helped to some extent, but the most effective solution was to just run the housing longer and shove enough extra into the downtube (and secure it with the bolt-on clamp at the exit point) so that it effectively wedged itself in place. Especially since the derailleur and brake are routed externally (rejoice!), I’d prefer if Nicolai had kept the routing that they used on the G16, where the dropper post also stays external until going into a port at the bottom of the seat tube.

And finally, it would be nice if the G1 had room for a water bottle. There is room on the size Large and up to strap one onto the frame forward of the rear shock, but there aren’t built-in mounts for it and the more compact dimensions of the Small and Medium sizes rule that out.

Mutators & Wheel Sizes

As I mentioned up top, the G1 has an unusual degree of adaptability, both in terms of geometry and wheel size options. Go read the “The Frame” section above for the rundown on those, but there’s a lot to experiment with on the G1. This section is going to go pretty deep on a variety of setups I tried, and if that’s too much detail, feel free to skip it. And it’ll probably help throughout if you reference the tech sheet, which lists geometry for each of the setups I’m describing below.

The biggest throughline from all of it is that the adjustments on the G1 feel much more like a way to exactly tailor your G1 to your personal preferences than a way to transform it into an entirely different bike. The fact that they’re relatively (though not quite entirely) independent of the suspension kinematics probably helps there. Some bikes’ geometry adjustments also have a significant impact on the suspension feel, but that’s not the case here. Instead, the G1’s adjustability feels comparatively subtle, at least if you don’t do anything too weird and deliberately off-base with it. I’m not going to go into detail on every single possible combination that I tried, but rather run through the main points and the sorts of tradeoffs that they introduced.

Full 29er

The G1 frame arrived with the shortest 33 mm chainstay mutators installed and the 3.5 mm seatstay ones in place. But Geometron’s mutator chart lists 0 mm of seatstay mutator as the default option for a Medium 29er, so I started there. And it turns out that the rear tire — a 2.4’’ Maxxis Minion DHR2 — just barely rubbed the seat tube at bottom-out in 175mm-travel mode. When I say just barely, I mean it — it wasn’t actually noticeable on the trail, and the bike still rolled nearly freely with the rear shock spring removed and my full body weight on the seat. But it did leave a mark on the seat tube, and Geometron told me that they’d gone to suggesting a 3.5 mm mutator (as the bike shipped) for that reason.

So I put the 3.5 mm setup back in, and while that solved the tire buzz, the higher bottom bracket that resulted made the bike feel just a little less stable, and detracted from the feeling of being “in” the bike, especially when pushing the rear end through fairly well supported corners. It wasn’t a huge change, by any stretch — the beauty of the whole mutator setup is that it leaves a lot of room to fine-tune things — but it didn’t click for me quite as cleanly.

I also experimented with the longer 41 mm chainstay mutators (which produce 454 mm chainstays), paired with both the 6.5 and 3.5 mm seatstay mutators. The steeper option with the 6.5 mm seatstay mutators just made the rear end feel unwieldy and harder to bring around in tighter spots; going to the smaller 3.5 mm mutator and slackening the headtube out a touch (and therefore increasing the front-center) brought the bike back to a more balanced feel to me, but just made it more stable and less maneuverable in a way that I mostly don’t need. I’ve gone back to that setup a few times when I’m riding very straight, steep, fast trails but it’s a bit much for most of my riding. Going longer on the chainstays does increase the front tire grip if you’re riding a little more centered, instead of aggressively weighting the front wheel, but also makes the back end harder to bring around in tighter spots, and that’s just not a tradeoff that felt worthwhile to me, for where and how I ride.

Mullet

Next up was a mullet configuration, with a 27.5’’ rear wheel. I haven’t typically been the biggest fan of mixed-wheel setups, but was very curious to see if the added adjustability of the G1 would let me find a setup that mitigated the things I don’t love about mixed wheels in general — chiefly that it tends to make the rear end of the bike feel shorter and quicker to cut in when leaning into a turn, rather than cleanly arcing behind the front.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, given my preferences there, the G1 worked better for me as a mullet with the longer 41 mm chainstay mutators than the shorter 33 mm ones (paired with the 15 and 10 mm seatstay mutators, respectively, for essentially the same geometry apart from chainstay length). Going longer on the chainstays helped balance the bike better and reduced the instability of the smaller rear wheel somewhat, but didn’t fully get it back to the feel of the full 29’’ setup, and didn’t offer any major advantages to me. I don’t tend to have much trouble with butt-to-tire clearance, even on long-travel 29ers, and the unbalanced handling feel that I’ve been describing just doesn’t work great for my personal preferences and riding style. As I’ve written elsewhere — including in our review of the mulleted Santa Cruz Bronson — I can absolutely understand how some folks like the shaper turn-in of the small rear wheel. It does make the bike feel a little quicker and easier to snap around some tighter corners.

That said, if you’re mullet-curious but don’t want to commit to the setup, the G1 does a nice job of both letting you convert between all the wheel size options and giving you a lot of leeway to tinker with the geometry in each mode to get the handling feel just right. So if you’re a tinkerer who wants to dial in things to the Nth degree, there’s a lot to like here.

Full 27.5’’

I also experimented with running the G1 as a full 27.5’’ bike, and while it works pretty well, the geometry did start to feel slightly more compromised in that setup — the mutator system is impressively flexible, but it still has its limits. In short, there’s a finer line to walk in terms of keeping the bottom bracket from getting unwieldy low, without also making the bike comparatively steep. Nicolai recommends running an external lower headset cup to help get the front end up, but I just ran a Fox 40 at full 203 mm travel to achieve a similar result.

Still, I would have liked the front end a little higher and the bike a little slacker; more for fit and getting a little more front-center length to balance the weight distribution between the wheels than strictly needing slower, calmer steering. So I tried dipping down to a 3.5 mm seatstay mutator (6.5 mm is stock for 27.5’’ mode with the 33 mm chainstay option), and while that helped get the cockpit feel I wanted, it also dropped the bottom bracket a bit too low.

Bringing it Full Circle

I’m still very much a fan of 27.5’’ wheels in certain applications, and while the G1’s full 27.5’’ setup did away with some of the handling quirks and perceived imbalance of the mullet configuration, I don’t think it’s the best option on the G1 for most people. A whole lot of what’s great and fun about 27.5’’ wheels is how they’re a little quicker to change direction and easier to throw around than bigger ones, especially at speed, and on some bikes — the Santa Cruz Nomad is a great example — that fits in nicely with their overall character. But the G1 feels most in its element as a big, stable bike that’s most interested in going as fast as possible down something steep, and the added stability of 29’’ wheels fits better into that package.

And so after all that, I wound up setting on a full 29’’ setup with a sliver of a beer can as the only seatstay mutator, just to stave off the aforementioned seat tube rubbing, paired with the shorter 33 mm chainstay mutators. And that worked — the tire doesn’t rub anymore. Now, to reiterate, the rubbing didn’t really cause any issues, but it didn’t seem great, and my custom beer can mutators are both big enough to stop it and small enough to be totally undetectable from a ride-feel or geometry-change perspective. So I’m calling that a win.

I’ve also experimented a good bit with both the 162 and 175 mm travel modes, and the change that they make is also relatively subtle. Nicolai recommends running a 25lb-heavier spring in the 175 mm mode, to compensate for the slightly higher overall leverage ratio (especially early in the travel) which surprised me at first but having done some experimentation with 350, 375, and 400 lb springs, it actually feels right. With the 350 lb spring (their recommendation for my 170 lb / 77.1 kg weight, in the 162 mm mode) the overall firmness feels about right and I didn’t have any notable bottom-out issues, but the bike feels a little soft through the midstroke, especially when loading the suspension through the pedals in corners, and sometimes when hammering through a fast and rough, but not especially steep section. The 175 mm mode with a 375 lb spring holds the bike up a bit better in those situations, while still having very good initial sensitivity off the top; the same 375 lb spring in 162 mm travel also helps with midstroke support but feels a little too firm off the top. The 400 lb spring in 175 mm mode works well for me on rougher, faster, less-steep sections where there’s a bit more weight on the rear wheel and it’s taking repeated, heavy hits, but feels a bit firm when the trails get steeper and my weight bias shifts a little more forward. Especially since there’s very little difference in terms of pedaling efficiency, I’ve found that I prefer the 175 mm mode almost all of the time.

Comparisons

The most obvious comparison for the G1 is the bike it replaced, and as I’ve mentioned throughout, the G1 feels a lot more like a refined, updated version of the G16 than it does an entirely new model. The suspension performance, handling, and fit are all fairly similar. That said, the G1 does feel better refined on a few of those points, especially the cockpit setup — the taller stack height and steeper seat tube angle make for a more comfortable pedaling position.

The biggest difference is definitely the options for wheel size that the G1 affords. While the G16 technically can be run as a 29er (the rear triangle has clearance for the big wheel), it doesn’t have the same geometry adjustability as the G1, and so stuffing big wheels into the G16 results in a quite high bottom bracket and some rather quirky handling characteristics. Go read the section above for a whole lot more on how the different wheel sizes feel on the G1, but in short, the full 29er configuration feels significantly more stable than the 27.5’’ setup on either bike, and the mullet setup splits the difference to some degree.

The G1 also pedals a little more efficiently than the G16, and the effective top tube is noticeably shorter, which probably is a good thing for most folks on such a long bike — it’s a bit less stretched out when seated, and a little easier to keep the front wheel planted on very steep climbs.

The Range is the only bike here that’s arguably more bike than the G1, and they go about their goal of being big, stable, Enduro bikes very differently. The Range is significantly more planted to the ground and a bit more composed when things get really rough, but it also pedals a whole lot less efficiently, is less lively, harder to pick up / pop off things, and is slightly harder to muscle around in really tight spots. The Range also favors a more upright cockpit setup and a bit more rearward weight bias, whereas the G1 wants the rider to be a bit more forward and weighting the front end aggressively.

The 161 is probably the best comparison here (the G16 excepted) but there are still major differences. The G1 is quite a bit more stable, somewhat harder to maneuver in tight spots, has significantly better small-bump sensitivity, and doesn’t pedal quite as efficiently. The slightly more moderate seat tube angle on the G1 also makes it feel more natural when pedaling on flatter ground, though both are definitely biased quite a bit toward more winch-and-plummet type riding, rather than being all that fun or engaging at lower speeds and in more rolling terrain. If you’re intrigued by the G1 but want to go for something a little more moderate and quicker handling, the 161 is a very good call — both pedal well above average for this sort of bike, have fairly firm, supportive suspension, and are fairly similar in terms of the fit (comparing an S3 Privateer to the Medium G1) and type of body positioning that they encourage.

The Jekyll is the next closest bike here — like the G1, it pedals better than average for its travel class, and is a fairly long, stable, Enduro bike that feels oriented toward being ridden fast and pushed hard rather than being easy-going and engaging at lower speeds. But the G1 is more stable and composed at speed, whereas the Jekyll is a bit quicker handling and a little more versatile in terms of feeling somewhat less out of place in tight, rolling terrain.

The Gnarvana is significantly more plush and a little more planted than the G1, but the G1 pedals more efficiently and is significantly more stable at speed. Mostly, the G1 feels quite a bit more game-on than the Gnarvana, in terms of needing a more aggressive touch and more commitment to weighting the front end to come into its own, but is also more composed once you get it up to speed. The Gnarvana is still squarely a big hard-charging Enduro bike, but it’s a bit more versatile and less full-on than the G1. The Gnarvana also works best with a more neutral, centered body position, whereas the G1 favors a more forward-biased setup.

Similar story as the Gnarvana, but to a greater degree — the Capra is a very interesting blend of being fairly stable and feeling like a proper modern Enduro bike, while being notably easy-going for how stable and planted it is. The Capra is significantly more plush and planted than the G1, doesn’t pedal nearly as efficiently, and doesn’t take as much speed and aggression to start to work, but also isn’t as stable or composed at full throttle. The Capra works better than the G1 with more neutral body positioning (as opposed to needing to weight the front end fairly aggressively) and has a bigger sweet spot in that regard..

The new Megatower V2 gets a bit closer to the G1 in terms of stability than the Capra or Gnarvana, but it doesn’t close the gap all the way, and it’s significantly more plush and cushy feeling than the G1. The G1’s suspension is firmer and more supportive, and it pedals a bit more efficiently. Both are stable, speed-oriented Enduro bikes first and foremost, but the Megatower is a bit more forgiving and less game-on than the G1.

Extremely different. Both bikes favor a relatively forward body position, but that’s about it. The SCOR is way more versatile and playful feeling and the G1 is far more stable, planted, and focused on going fast all the time at the expense of being more demanding and less forgiving if you’re not pushing it hard.

Quite different. The Altitude is a bit more plush than the G1 and quite a bit quicker handling, but also way less stable and composed at speed. The Altitude is definitely more versatile in that it’s a lot easier to manage in tight spots and doesn’t need to be ridden as aggressively to come alive. The G1 also pedals a little more efficiently.

Super different. The Nomad is more versatile, much easier to throw around in the air, quicker handling, and quite a bit less stable. It’s also substantially more plush and forgiving if you’re not pushing it super hard. The more you’re interested in going fast all the time, the more sense the G1 makes; the Nomad is much more playful and freeride-oriented.

Who’s It For?

The Nicolai G1 is a bike that’s going to work best for riders with “solid” to “very good” bike handling skills who, first and foremost, want a bike that encourages them to push hard and go faster on steep, technical descents. It’s not particularly fun or engaging in tighter, more rolling terrain, but trades that off by being supremely stable and composed once speeds pick up, and still manages to be surprisingly maneuverable once it’s up to speed. And compared to the Norco Range — the G1’s only real competition for being the hardest-charging Enduro bike I’ve ridden to date — the G1 pedals a whole lot better, and is a much more viable option for huge days in the saddle, linking up a series of big descents. The G1 is pretty special at what it does, and while that won’t be for everyone, it’s no longer totally off in left field in terms of geometry, either, and is worth a second look for a lot of folks who are after a true big bike but have filed the Geometron project as being too off the deep end.

And if you want more info on how the G1 stacks up to the ever-growing class of ultra-burly Enduro bikes and which one might be best for you, Blister Members can always drop us a line through the Blister Member Clubhouse page, and I’ll be glad to talk you through the options.

Bottom Line

The Nicolai G1 is a big, stable bike that’s most at home trying to go fast on steep descents, and it does an extremely good job of filling that role while also pedaling back to the top quite well, particularly if the climbs are on the smoother, less technical side. It’s not especially versatile in terms of either the type of terrain or the riding style that suit it best, but if you want a bike that’s impressively composed when going very fast (and are tall enough to fit on at least the not-very-small size Small), it’s an outstanding option. It’s also exceptionally well built, offers an incredible range of adjustability to let riders fine-tune the fit and handling to their hearts’ content, and offers some of the biggest sizing on the market for folks at the ultra-tall end of the spectrum.

Just adding my own measurments:

XL frame: 3‘930g without shock but incl. rear axle and hopetech seat clamp.

EXT Shock is 800g with 400lbs spring.

I am riding mine at 16.7kg without pedals (EXO tires but regular CC front and back, heavy Chris King hubs, Fox38)

Really curious on the EXT performance as well. That negative spring addition sounds like it made it to the new “E-Storia” spec (amongst other changes). I am currently weighing selling my Storia and buying that new E-Storia when available or sending my Storia in to refit it to a new bike (different shock length, stroke, tune, etc) for $450. The feature list on the E-storia all sounds positive from my Storia experience, but real-world experience and review trump marketing jargon

The beer can mutator is hilarious. Think I’d need a dual-ply can shim to clear a maxxis 29×2.5? I’m going to try it.

Living in the UK I got to spend a day with Geometron riding different sizes and set-ups before buying. I was making a big switch from a Large StumpJumper Evo to the G1 as my riding had gone back to being much more toward Enduro/Bike Park. What is interesting is that I am 182cm and I ended up going for the XL. I switched between frame sizes multiple times but the XL just ‘felt’ better when pushing on. Definitely not a playful bike at that size but offers huge stability at speed.